c. 1951-1952—Monterey, California

The Zappa family moved away from Edgewood, Maryland, in November 1950.

I want to dispel an erroneous statement that our family moved to California in 1950. I was born in 1951, so I am 11 years younger than Frank and we moved to California that same year. [...] We lived in Monterey, Pacific Grove, Montclair and Claremont, San Diego and I went to high school in Pomona.

My father was working in civil service and he was moved all over the country, and, by a process of elimination we wound up in Southern California. We almost wound up in Dugway, Utah at one point because he had been offered a job at this place where they were developing nerve gas during World War II. He came home one day, with photographs of this area, and asked how we would like to move there. No way! It was hideous! So we got off lucky on that one.

My Dad had gotten another offer to work at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah (where they made nerve gas), but we got off lucky—he didn't take it. Instead, he took a position at the Naval Post-Graduate School in Monterey, teaching metallurgy. I had no idea what the fuck that meant.

So, in the dead of winter, we set out in our 'Henry-J' (an extinct and severely uncomfortable, small, cheap car manufactured then by Kaiser), via the Southern Route, to California. The backseat of a 'Henry-J' was a piece of plywood, covered with about an inch of kapok and some stiff, tweedy upholstery material. I spent two exhilarating weeks on this Ironing Board From Hell.

The Zappa clan made its way to California in December 1951. We came west in a Henry J my Dad purchased for the trip to California. [...] We ended up in Monterey—all expenses paid by the U.S. Navy.

The first house Mom and Dad rented in Monterey [...] was an old two-story Victorian with a wrap-around porch and a big kitchen.

On 9 June 1909, Secretary of the Navy George von L. Meyer signed General Order No. 27, establishing a school of marine engineering at Annapolis, Maryland. [...] The Naval Postgraduate School moved to Monterey in December 1951.

c. 1952-53—410 Sinex Ave., Pacific Grove, CA

After living in Monterey for only eight months we moved to Pacific Grove. We left the big Victorian house we had come to love and the Portuguese families we were finally developing a connection with. We ended up in a smaller rental not far from the center of Pacific Grove.

"Local Happenings," Pacific Grove Tribune, August 22, 1952, p. 4

[...] Attendance at the Monterey County Fair this week was the first time for Mr. and Mrs. Frank Zappa, Sr and their family. They came out in December with the post graduate school from Annapolis. Mr Zappa, of the civilian staff, is with the metallurgy department.

They have purchased their home at 410 Sinex and look to a long stay here. There are three boys, Frank, Bob, Carl and a four months old daughter Patrice Joanne. The family are originally from Maryland. [...]

The Moonlight Bayers

"Entertainers At Recent Fair," Pacific Grove Tribune, August 22, 1952, p. 5

Inspired by their summer school music training in Pacific Grove, one young group formed "The Moonlight Bayers" and were well received on the Fair entertainment program. In the Bayers were Frank Zappa Jr., Bob Zappa, Charles Weitzeil and Ronald Dodge.

All are pupils of Pine Avenue School. They made their debut at the summer school closing music program. The youngest, Bob, is a fourth grade pupil. The others are entering the Junior High. Bob also got started on the tonette at the summer session, in addition to vocal work. At the Fair they were on the program each morning.

Robert Down Elementary School, 485 Pine Ave., Pacific Grove, CA

"Pine Avenue Echoes," Pacific Grove Tribune, October 10, 1952, p. 6

[...]

"Seventh Grade Class Officers"

During the past two weeks the various seventh grade rooms have been their class officers [...]. The 7-7 of Mr. Wehrly selected, Skipper Kulcsar as their President, Patsy Sanders as Vice-President, Frank Zappa as Secretary and Tommy Mix as Sergeant-at-Arms. [...]

"Pacific Grove High School News, Pacific Grove Tribune, November 7, 1952, p. 5

[...]

Dramatics Class Present Play

At last Friday's assembly the flag salute was led by Sergeant-at-Arms Neil Orchard. Mr Washburn and the School Orchestra played three numbers. Then, Miss Haller's Dramatics Class put on a play, The Soft Hearted-Ghost.

Those appearing in the play were Frank Zappa as Father Ghost, Claydene Johnson as Mother Ghost, Peter McReynolds as the Soft Hearted-Ghost; Virginia Bock as the Fortune Teller, Orville Fry as Bill Templeton, Barbara Neal as Bill's Girl, Lloyd Firstman as the Master of Ceremonies, Pat Chamberlain as Silas P. Static, Diane Ducharme as the Girl, and the following attending the party: Sandra Calkin, Sereta Ault, Carol Gillespie, Leota Bock, Ellen Torrance. The stage manager was Mickey Cardoza.

The audience was most appreciative of this first effort by the Holiday Players.

The Zappa Family Social Life

Social And Club Activities, Monterey Peninsula Herald, October 10, 1952

St. Angela CDA Adds Members at Monday Meeting

Court St. Angela, Catholic Daughters of America, added 18 members Monday night in impressive initiation ceremonies at the Pacific Grove Woman's Civic Club.

[...]

The court's new members include Betty Jo Bettencourt, Mary Carney, Wanda Flores, Ellen Heady, Theola Leighton, Lorraine Loustaunau, Pat Mathewson, Helen Morin, Mary Catherine McHale, Edna Niell, Eleanor Noel, Patricia Quigley, katherine Rokop, Frances Selbicky, Helen Tobin, Roberta Watson, Rosemarie Zappa and Stella Zonski.

"Local Happenings," Pacific Grove Tribune, December 5, 1952, p. 8

The Sun Maybe Slow—But It Does Arrive

Thanksgiving Day was a get together occasion for the Leroy Smith and Frank Zappa families. Mr and Mrs Zappa were host and hostess at their home on Sinex Avenue. The youthful group were the children, Bob, Frank, Carl and Patrice Joanne.

There may have been some shop talk. Messrs. Zappa and Smith are on the civilian staff in the metallurgy and electrical departments of the Post Graduate School. They came out with the school from Annapolis a year ago.

Mrs Smith and Mrs Zappa decided that "waiting all summer" to wear their strictly summer wardrobes they could finally "give up and store them away." However with this concession to the Weather Man whom the newcomers thinks has "got his season crossed" in the area, the dinner group found the November holiday perfect for an afternoon ride in warm sunshine, to enjoy the scenic beauty of the peninsula coastline.

LM Thompson, "Neighborhood News," Pacific Grove Tribune, March 20, 1953, p. 6

Mr. and Mrs. Zappa at 410 Sinex are on the last lap of their recent painting contest-house painting, that is, as a result their home has taken on a new look. Mr. Zappa took over the painting for the upper part of the house, Mrs. Zappa did the lower part.

Of course, it might be that Mrs. Zappa got in some extra time when her husband was no' about to check up. Saturdays were his only time to devote to the paint brush.

Lettuces or Artichokes

At one time [my father] was teaching at the Naval Post-Graduate School at Monterey, California, and we were so poor then that on weekends [...] we would drive toward Salinas and try to find a lettuce truck and wait for something to fall off it.

Pacific Grove isn't far from a place called Castroville, which, according to the Chamber of Commerce, is the "Artichoke Capital of the World."

[...] On Saturday mornings in the summer, Dad packed Frank and me into the car. The three of us headed to the artichoke farms in Castroville. [...] Dad waited for the trucks headed to town to stop and deliver the crops for shipment.

[...] We waited for the trucks to turn off of the dirt roads when they cme from the fields and drove toward the highway. Artichokes bounced out when the truck tires made the jump from dirt to asphalt.

Dad turned Frank and me loose to grab the free artichokes. [...] Artichokes, iceberg lettuce, and broccoli were what he considered prize catches.

Puppets

We moved from Monterey to Pacific Grove, a quiet town nearby. I spent my recreational hours building puppets and model planes and making homemade explosives from whatever ingredients I could find.

During this period, Frank spent time concentrating on creative efforts. He finally got Dad to get him a model plane kit and was meticulous at putting it together.

He also constructed landscapes out of cardboard and made puppets out of paper mache, felt, wire, and pieces of cloth. This was the same time he developed a curiosity about explosives.

Driven to rely in his own resources, he built model planes, conducted puppet shows using figures he had made and clothed himself, and pursued an ongoing fascination with explosives that led to several potentially harmful accidents

My brother-in-law, Jett Spencer, told me recently that he and Frank would actually present the puppet shows at the Grove Theater and they were filmed . . . to be shown during the Sat. matinees later.

In the early 1950s, I'm not certain of the exact year but I suspect it was 1953, Frank was a student at Robert H. Down school on Pine St. In Pacific Grove, CA. He along with myself and another friend had a puppet show called "Madcap Puppets." The third friend's father built the stage. Even then Frank was a superb promoter. He got us booked on to a children's show on live TV in Salinas, arranged to have us perform on stage during Saturday afternoon intermissions at the Pacific Grove Theater, and as a stage act at the Monterey County Fair in Monterey. The only part of the act I recall clearly was a takeoff by Stan [Freberg] of the popular TV crime series, "Dragnet," which [Freberg] re-titled "St. George and the Dragonet." So far as I know, this was Frank's first real show business success.

Stan Freberg's St. George & The Dragonet was released in 1953, so that fits.

The third person was Jett Spencer, although at the time he used his middle name, Monroe, as his given name. Incidentally, as I remember it, we performed our shows live at the Grove Theater. The manager had an early 8mm camera and he did film us but I don't recall his showing the films publicly. I don't remember the name of the tv kid's show on which we appeared, but the station was KSBW Ch 8, Salinas, CA. It has the same call letters today. I can't say for certain how long Frank lived in P.G. but my hazy recollection is that it was about a year. As for photos or film of our show, I don't know of any. About a year ago I happened across an email address for Frank's widow and I wrote to ask whether Frank had ever mentioned the P.G. shows. In a gracious response, she said that he had when she asked him about a small costume she had found tucked away. He said it was from the Dragonet bit. Finally, this was my only experience with puppets.

According to wikipedia, KSBW started broadcasting on September 11, 1953.

At least during the Pacific Grove period we used hand puppets.

Charles Ulrich, December 12, 2013

Today I talked with Jett Monroe Spencer, who did puppet shows with FZ in Pacific Grove. He confirmed some of the details previously provided by Bill Dorman on affz. They were known as Madcap Puppets. Spencer's father built the puppet stage. They performed at the local movie theatre, the county fair, and on the Salinas television station.

He said that their shows for the movie theatre were filmed in advance (as his brother-in-law Chet Zebroski reported second-hand on affz), whereas Bill Dorman remembered performing live.

He remembered two Stan Freberg records they did puppet shows to: St. George & The Dragonet (mentioned by Dorman) and Banana Boat Song. Later, FZ wrote original scripts for the puppet shows.

He mentioned making explosives out of ping pong balls.

Margery Bush, "Neighborhood News," Pacific Grove Tribune, September 3, 1953, p. 2

Big Rec Club Show Ends Summer Season

The Rec Club will close its summer season tomorrow night with a talent show, arts and handicraft display, puppet show, folk dancing exhibition by various classes from the three playgrounds and the awarding of ribbons for tournaments.

The program will start at 7:30. Parents are invited.

Margery Bush, "Neighborhood News," Pacific Grove Tribune, September 10, 1953, p. 3

The Mad Cap Players is the result of "a crazy idea I got after school let out," explained Frank Zappa, young son of Mr. and Mrs.Frank Zappa of 410 Sinex. "So I got these fellows together and told them if they would cooperate, and be willing to put in some hard work, we might manage to get passes to the Fair this year and also put on a few puppet performances."

Frank wrote the three scripts with Monroe Spencer helping out by listening and the variety show script was the one that got Mrs. Clyde Dyke's approval. Mike Smith completed the cast with Bill Dorman being added at the last minute as the announcer.

They gave three shows at the Fair and have some pretty good ideas about TV puppet shows. And they did get those passes!

Special thanks to Javier Marcote for the Monterey Herald Peninsula and the Pacific Grove Tribune articles.

c. 1954—Oak Park Drive, Claremont, CA

A real estate listing for 257 Oak Park Drive in Claremont bills the house as "the Childhood Home of Legendary Musician Frank Zappa!"

The house for sale was the one we moved to first in 1952, I was a baby, and Frank was about 11. It was the house next to it that we lived in around 1958-1959.

Bobby Zappa, July 17, 2006

We moved to Claremont, not Pomona, in 1953. That was the first time we lived there.

In 1954, after living in Monterey and Pacific Grove for three years, Dad moved us to Southern California. I was 10 and Frank was 13 and neither of us was happy about leaving Northern California. [...] Dad did get a better job. It was with Convair, a defense contractor in Pomona, California.

"Claremont's nice," said Zappa. "It's green. It's got little old ladies running round in electric karts."

c. 1954—Claremont High School, Claremont, CA

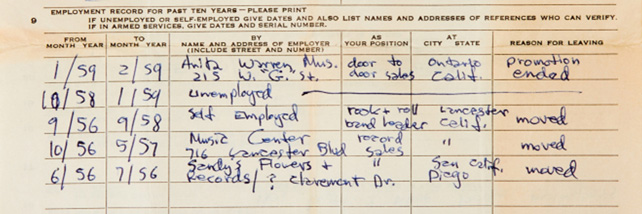

During the '50s, I went to four separate high schools. Although each was in Southern California, their images were distinctly different. I went, in chronological order, to Claremont High School in Claremont, Grossmont High School in El Cajon near San Diego, Mission Bay High School in San Diego, and Antelope Valley High School in Lancaster, where I graduated.

[Frank] attended the junior high section of Claremont High School. He also used to visit a music store in Claremont called the Folk Music Center on Harvard Avenue.

[...] After we settled in Claremont, Frank and I became more comfortable in our new hometown and we were able to make friends. For Frank, his interest in music became his connection.

He joined the orchestra in junior high playing drums. He participated in band performances and he got to know other students with similar interests in music.

1955—Mortensen Meets Zappa

Vic Mortensen: I went to Claremont High, and that's when I (first) met Frank Zappa, when I was in the marching band in seventh or eighth grade, I don't know which. We had to go out and play (at) a football game, and in those days, the (drum) skins were literally skins. You would get out and it would start to "mist up" a little bit, and you'd keep tightening your heads, otherwise, you'd play the national anthem and it would sound like a funeral dirge, because everybody's playing a tom-tom. OK, then you get back on the bus and you kept loosening up and loosening up and loosening up. I've heard drums explode. So, I had gone up to the band room, to make sure that the drumheads were still loose enough. There was this crazy guy in there who had taken all of the band drums and lined them all up and had tuned them down to tom toms. He was going "bump bump a diggy bump bump a diggy bump bump." I said, "What the . . . are you doing?" He said, "Wow, man, I don't have a drumset and I just wanted to try out some different sounds." I asked, "How'd you get in here?" and he said, "Well, I know the guy" (probably referring to the janitor). I was fascinated. He was doing some pretty good things. Didn't see him again until I was a freshman in high school. Never forgot him—that's how we got together years later. [...] He was about a year older than I was. He couldn't have been much older. I had never seen him around the school. I said there were five hundred kids and there was "a dude in the band room that I had never seen at school."

Many from the Claremont High Class of 1958 remember him. "Yep, he was there," said Karl Hertz, who sat three rows ahead of Zappa in Eleanor Galloway's English class. "We all knew Frank," concurred Jerry Peairs. "He may not have stayed a year or ended a year, but he was there." [...]

In a conversation at a Claremont record shop about the then-famous Zappa, the clerk, Doug Galloway, said his mother had taught Zappa. The English teacher remembered him, Galloway told [Murray] Gilkeson, because his vocabulary was so large, she had to look up some of the words he used in essays.

[...] Gilkeson has found about 20 students who remember Zappa from eighth and ninth grade. At the breakfast, Hertz, Peairs and Stu Holmes said Zappa drummed in the marching band, produced a wall-sized mural of outer space for a science project and cut up in English class. Gilkeson has collected more anecdotes, of Zappa reciting a poem in front of one class and participating in a skit in another, absorbing information without taking notes, ad-libbing a science talk in a German accent. "Everybody knew Frank. He was just a little off-center," Diann Irvine told Gilkeson.

Case in point: Classmates John Peek and Nelson Scherer told Gilkeson that they and Zappa did a puppet act on a talent show on KHJ, placing second. Puppetry is an unusual hobby for a teenager, I remarked at the breakfast. "Some of us were car guys, and Frank was into puppets and music," Peairs observed.

One student could place Zappa firmly in the ninth grade. Steve Thorne told Gilkeson that his family moved to Claremont in 1954, when he started ninth grade, and that he ate lunch with Zappa, who was in his class. [...] A photo from an eighth grade talent show, which appears in Claremont's El Espiritu yearbook of 1954, is said by classmate Barbara Norton to depict Zappa, whom she knew well—although, frustratingly, the boy in the photo isn't named.

Charles Ulrich, December 4, 2013

I finally talked with Nelson Scherer, who did puppet shows with FZ in Claremont.

The most important information he provided is that Claremont High School was a six-year school (grades 7-12) at that time and they were in eighth grade when they did puppets.

Puppets

The Ewings lived a few doors down the street and Zappa made puppets with their son, which they entered in the LA County Fair. They soon fell out and Zappa became a solo puppet master.

July 18, 1955—Disneyland

On July 18, [1955,] Disneyland Amusement Park opened to the public. [...] We went to Disneyland that first day it opened. Frank had been anxious to see the park, because he knew there would be lots of shapely teenage girls running around.

R&B

I didn't really get into contact with anything that resembled musical expression until I was about 14 or 15 years old, which is when I got to hear some of it on the radio. I remember riding around in a car and by accident while somebody was turning the station, we came across some oddball station out in Chino, California that was playing a record called "I" by the Velvets.

[...] They were playing "I" by the Velvets and I said, "What was that?" And my father says, "No, turn it away! Don't listen to that!" And then that gave me the first inkling that there was something interesting about to happen in the world, then about a week later I heard, I went looking for that same radio station where the weird music was coming out of, and I mashed to hear another record called "Riot In Cell Block Number 9," by The Robins, then proceeded to go to a place that actually sold records, I'd never been to a record store before, I thought that was a good place to start and went in there, and in those days you could take a record into the little room and listen to it before you bought it, so I snatched up "Work With Me Annie" and two or three other . . . A Joe Houston record, and I listened to it and I was hooked!

FZ, interviewed by Ralph Denyer, Sound International, April/May 1979

One day we were driving around in the car and a famous record came on the radio. It was called "I" by The Velvets on the Red Robin label. I thought: Boy, that sounds really great. My parents were saying: Turn that screaming nigger music off the radio! That wasn't even a screaming nigger record, it was just a nice ballad. I thought maybe there was more of the same music where that came from. I started checkin' round and sure enough there was. Shortly thereafter I managed to convince them life was impossible without a record player and that is when the trouble began.

[...] When we got the first record player they gave my mother a record with it called "The Little Shoemaker" by some white harmony group, I can't remember who. It was a really stupid record and she used to listen to that while she was ironing, she wasn't that into it. My father used to play guitar when he was in college with some little troubadour type band, playing all kinds of old songs. But he hadn't touched it in years, it would just sit in the closet.

Around the time of his thirteenth birthday, Frank was riding in the Henry J with his parents when "Gee" by the Crows came on the radio, followed by the Velvet singing "I." "It sounded fabulous," said Zappa. "My parents insisted it be dismissed from the radio, and I knew I was on to something . . . "

Special thanks to Murray Gilkeson.

1954-1955—El Cajon, California

After a year of living in Claremont we packed up and moved farther south to El Cajon, a town east of San Diego. [...] Frank started the ninth grade at Grossmont High in El Cajon.

In 1954, we moved to San Diego.

Gary Titone, December 8, 2024

I went through the entire 1955 San Diego White Pages on Microfilm to find The Zappa Home in El Cajon when Frank bought The Varese Album in La Mesa, California. What made this mission more difficult was White Pages back then were not A to Z for all of San Diego. I had to go through each street in El Cajon, where each street had names A to Z, not knowing name of street and only town it took quite some time.

Frank V Zappa

749 El Monte Road

El Cajon, California

Grossmont High School

At Grossmont High School, the only things the kids had to be proud of were the size of their student body and the fact that their marching band was really spiffy. Grossmont didn't have just middle and upper middle-class whites, but those it did dressed Buckle Back, though not as severely as Claremont. They wanted to go to San Diego State 'cause they thought it was swinging, or Tempe, in Arizona, 'cause they had heard it was a party school. Their image was superficially clean. They didn't come to class drunk out of their minds; they saved boozing for the weekend.

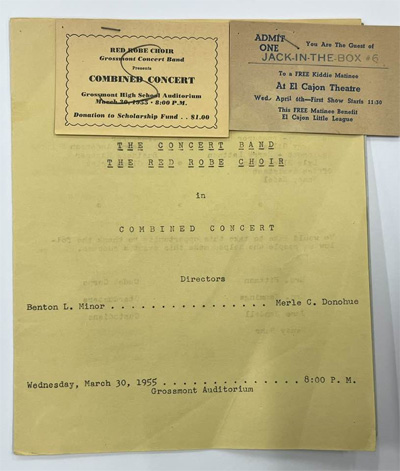

The music teacher at Grossmont (High School) was a guy named Benton Minor, who signed all his passes 'B. Minor.'

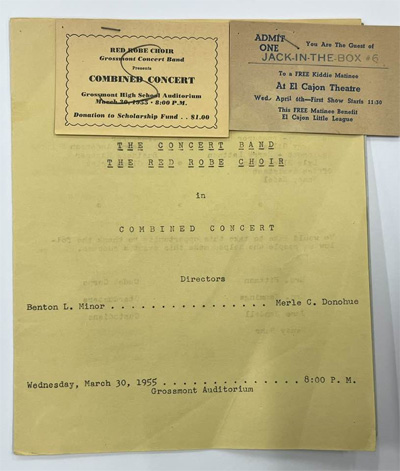

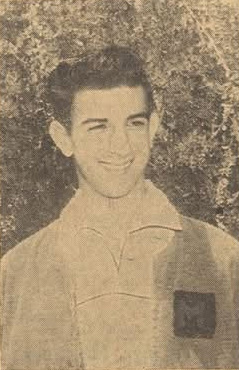

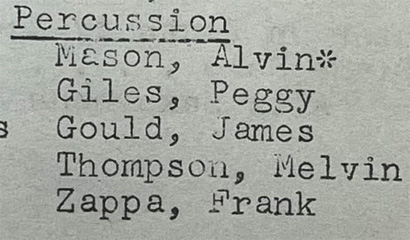

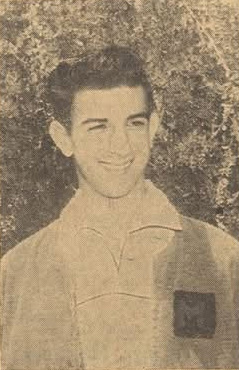

Previously unidentified Frank Zappa 1955 yearbook photo? It has been previously established by others including Frank Zappa and Grossmont High School, El Cajon, California representatives that Mr Zappa attended said school at least in the spring of 1955. A March 30, 1955 Grossmont High School Combined Concert program I recently researched references Frank Zappa by name as a band personnel percussionist.

[THE CONCERT BAND

THE RED ROBE CHOIR

in

COMBINED CONCERT

Directors

Benton L. Minor . . . Merle C. Donohue

Wednesday, March 30, 1955 . . . 8:00 P.M.

Grossmont Auditorium]

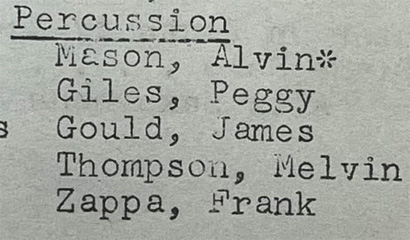

[Percussion

Mason, Alvin*

Giles, Peggy

Gould, James

Thompson, Melvin

Zappa, Frank]

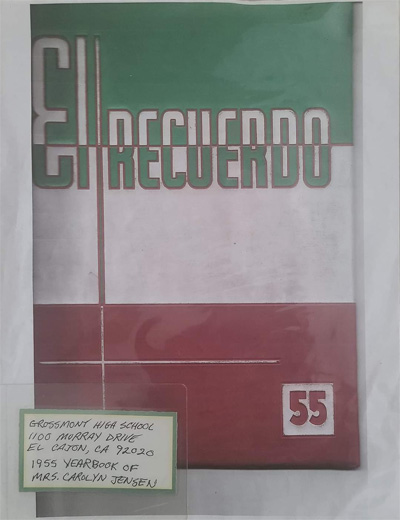

That years High School year book, "El Recuerdo" contains a photo of the band with an individual standing in the percussion section looking (to me at least) like Frank. Unfortunately no band members are identified by name on this photo and Frank does not appear in photo or name elsewhere in this yearbook.

School representatives were recently excited to see my yearbook and Concert program discoveries that had not been previously brought to their attention. I was at first skeptical that Frank would actually wear a band uniform but it has been pointed out to me that he did indeed as he marched in several Grossmont events—more details on that later.

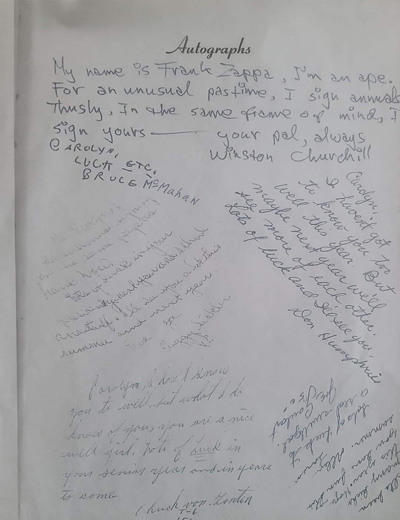

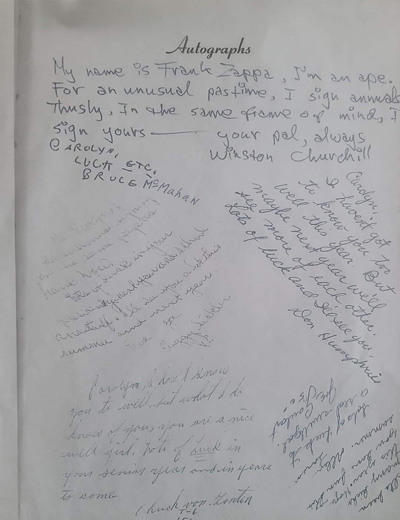

FZ's autograph, Mrs. Carolyn Jensen's yearbook, El recuerdo 55, Grossmont High School

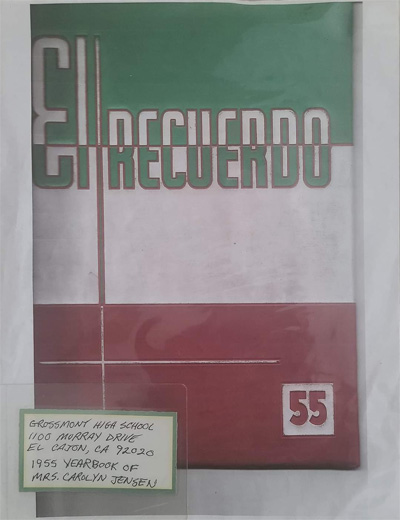

El Recuerdo 55

Grossmont High School

1100 Murray Drive

El Cajon, CA 92020

1955 Yearbook Of

Mrs. Carolyn Jensen

My name is Frank Zappa, I'm an ape. For an unusual pastime, I sign annuals. Thusly, in the same frame of mind, I sign yours.

Your pal, always

Winston Churchill

[...]

March 1955—Blackboard Jungle

In my days of flaming youth I was extremely suspect of any rock music played by white people. The sincerity and emotional intensity of their performances, when they sang about boy friends and girl friends and breaking up, etc., was nowhere when I compared it to my high school Negro R&B heroes like Johnny Otis, Howlin' Wolf and Willie Mae Thornton.

But then I remember going to see Blackboard Jungle. When the titles flashed up there on the screen Bill Haley and his Comets started blurching "One Two Three O'Clock, Four O'Clock Rock . . ." It was the loudest rock sound kids had ever heard at that time. I remember being inspired with awe. In cruddy little teen-age rooms across America, kids had been huddling around old radios and cheap record players listening to the "dirty music" of their life style. ("Go in your room if you wanna listen to that crap . . . and turn the volume all the way down.") But in the theater, watching Blackboard Jungle, they couldn't tell you to turn it down. I didn't care if Bill Haley was white or sincere . . . he was playing the Teen-Age National Anthem and it was so LOUD I was jumping up and down. Blackboard Jungle, not even considering the story line (which had the old people winning in the end) represented a strange sort of "endorsement" of the teen-age cause: "They have made a movie about us, therefore, we exist . . ."

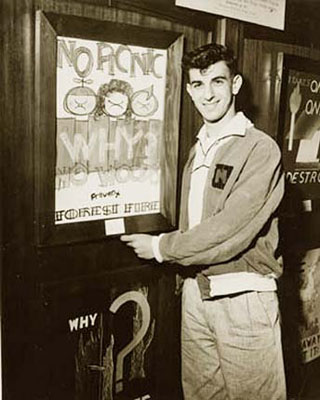

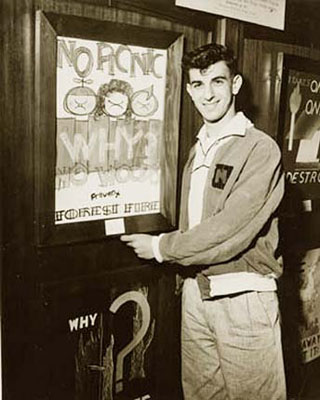

April 13, 1955—"No Picnic"

"Grossmont Youth's Fire Poster Wins," unidentified source & date, 1955

NO PICNICS?—Frank Zappa, Grossmont High School ninth grade student, poses with the prize-winning poster in the Fire Prevention Week contest sponsored by forest services here. Thirty county schools participated in the contest, entering 399 posters.—Staff Photo

Foothill Echoes, "Frank Zappa Wins Poster Contest; Freshmen Receive Awards Of Merit," Grossmont, California, May 10, 1955

Frank Zappa, 9th grade, submitted the winning poster to the annual poster contest held by the California Division of Forestry, April 13. "There were 399 entries from 30 schools," said James G. Fenlon, State Forest Ranger.

An oil painting donated by the Citizens Study Group was awarded to Frank Zappa for his winning entry. Another oil painting with a plaque was awarded to Grossmont. This painting will be rotated to the winning school each year.

FRANK ZAPPA

Paul Roberts Valley Studio

R&B & Varèse

I think the very first record I got was a 78 of "Riot in Cell Block Number Nine."

FZ's letter to Edgard Varèse, August 1957, from Felix Meyer (ed.), Edgard Varèse, Composer, Sound Sculptor, Visionary, The Boydell Press, 2006, p. 403-404

It might seem strange but ever since I was 13 I have been interested in your music. The whole thing stems from the time when the keeper of this little record store sold me your album "The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, Vol. 1." The only reason I knew it existed was that an article in either LOOK or the POST mentioned it as being noisy and unmusical and only good for trying out the sound systems in high fidelity units (referring to your "IONISATIONS" [sic]). I don't know how the store I got it from ever obtained it, but, after several hearings, I became curious and bought it for $5.40, which, at the time[,] seemed awfully high and[,] being so young, kept me broke for three weeks. Now I wouldn't trade it for anything and I am looking around for another copy as the one I have is very worn and scratchy.

FZ, interviewed by Kurt Loder, Rolling Stone, 1988

The first music that I heard that I liked was Arab music. But I can't imagine where I heard it, because my parents didn't even have a record player until I was fifteen. Then, finally, they got a record player, and I think the first rhythm & blues record that I got was "Riot in Cell Block #9" by the Robins. And shortly thereafter, I read an article about Edgard Varese in Look magazine, and I found the Varese album, and so that's what I had. I had the Robins and Varese, and I think I got "Work with Me, Annie," by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, too.

[...] I saw it as a totally unified field theory. What appealed to me in the Varese album was that the writing was so direct. It was like here's a guy who's writing dissonant music and he's not fucking around. And here's a group called the Robins, and they didn't seem like they were fucking around, either. They were havin' a good time. Certainly Hank Ballard and the Midnighters sounded like they were having a good time. And although harmonically, rhythmically and in many other superficial ways it was very different, the basic soul of the music seemed to me to be coming from the same universal source. You know: a guy who had the nerve to stand up and say, "This is my song, like it or lump it."

Back then, my record collection consisted of five or six rhythm-and-blues 78-RPM singles. [...]

One day I happened across an article about Sam Goody's record store in Look magazine [...]. The article went on to say something like: "This album is nothing but drums—it's dissonant and terrible; the worst music in the world." Ahh! Yes! That's for me!

I wondered where I could get my hands on a record like that, because I was living in El Cajon, California—a little cowboy kind of town near San Diego.

There was another town just over the hill called La Mesa—a bit more upscale (they had a 'hi-fi store'). Some time later, I was staying overnight with Dave Franken, a friend who lived in La Mesa, and we wound up going to the hi-fi place—they were having a sale on R&B singles.

Puppets

The first thing I ever did in "show business" was to convince my little brother Carl to pretend he was my ventriloquist dummy, sit on my lap and lip-sync "Riot In Cell Block Number 9" by the Robins at the Los Angeles County Fair.

[...] I used to build models (not from kits, because I couldn't follow the simple instructions). I used to build and sew clothes for puppets and marionettes. I used to give puppet shows using Stan Freberg records in the background.

That's how I got started in, let's say, show business. Some of the first things that I did involved puppets, and I've always liked puppets.

George Latshaw, Puppetry Journal, winter 1984

[FZ] said he had done puppets of all sorts back in the 50s, even painting lines on his brother's face to turn him into a vent figure. Zappa used his index fingers to trace the pattern from the corners of his mouth down below the jaw line to indicate the marks of a dummy's moveable mouth. It was logical to use puppets for his concert, because he couldn't get the kind of imagery he wanted by using people.

[Time For Beany] was that rarest, most elusive of creatures: A kids' show that adults enjoyed watching—and not just any adults. Among its declared fans were Groucho Marx, Albert Einstein and the kid who would grow up to be Frank Zappa. (Allegedly, Einstein once cut short a high-level meeting on quantum molecular mechanics by announcing, "Excuse me, gentlemen, but it's Time For Beany!")

[...] Time For Beany was damned clever. Actually, there were many clever folks involved in its production but its producer-creator and its two performers were three of the cleverest humans ever in show business. They were, respectively, Bob Clampett, Stan Freberg and Daws Butler.

And the thing that I like about Albert Einstein and I hope it's not an apocryphal story—He liked the television show that I liked, which was Time For Beany. I heard a story that he left an important meeting one time telling the people he had to go watch Time For Beany. And I hope that's true.

Additional informant: Guillermo Laso.

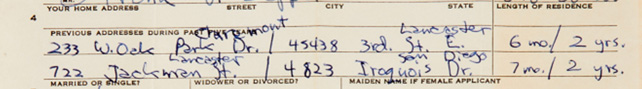

1955-1956—Clairemont, California

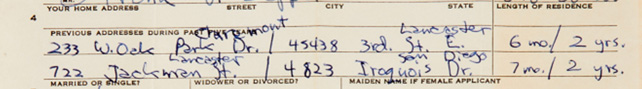

4823 Iroquois Dr., San Diego / 2 yrs.

Bobby Zappa, July 22, 2006

We lived in Claremont, California twice. We also lived in a town called CLAIREMONT (different from the other one) after we lived in El Cajon before we moved to Lancaster. We lived in that Clairemont for about a year after El Cajon, so that would be from 1955 to 1956—then in 1956 we moved to Lancaster and in 1959 back to Claremont, the town near Pomona.

After a year in El Cajon we moved again. This time we didn't move far, just a little farther northwest to a small town called Clairemont—not to be confused with Claremont near Pomona.

Electronic Music

Synapse: When did you first become aware of the synthesizer?

Zappa: I've known about the synthesizer since I read about Oscar Sala's Mixtur Trautonium, and it's been over 20 years. It was reported in this article that it makes sounds like chordal glissandos of kettle drums and things like that, and I said, hey, that's for me, but of course in those days there were no synthesizer records, and anybody who was dealing with electronic music had to be in "New York."

Synapse: Were you aware of other people doing things in Europe, like Stockhausen, and people

Zappa: This was before Stockhausen.

Synapse: But in the early 50's, after the war, when they started doing tape pieces?

Zappa: Yeah, Pierre Henry and yeah, I knew about that stuff. In fact there was a record store in Clairmont California that occasionally got some of these unusual, very rare recordings, and since it was so primitive in those days, you could actually go into a record store and listen to the record before you bought it. I actually went in there and listened to that music. I had a chance to really hear it. Of course I couldn't afford to buy it, but I heard it. I have since acquired a lot of those records, though. I have a pretty good collection of electronic music.

1955-1956—Mission Bay High School, San Diego

Mission Bay was different. First, it was a very transient neighborhood; a lot of the kids' fathers worked in the navy. It was definitely juvenile delinquent territory. You wore a leather jacket and very, very greasy hair. You carried a knife and chain. If you were really bad, you mounted razor blades in the edge of your shoes for kicking. Also, you made sure you carved up the school's linoleum floor by wearing taps on your soles. If you failed to do any of these things you would (1) not get any sex action, and (2) probably be injured.

Frank was now in tenth grade attending Mission Bay High School on Grand Avenue in San Diego. Mission Bay High was a tough place. It was filled with pachukos, Mexican gangs who fought with white kids and the other pachuko gangs.

[...] I wasn't concerned about grades and never felt competitive with other students because so many of our moves occurred in the middle of a school year.

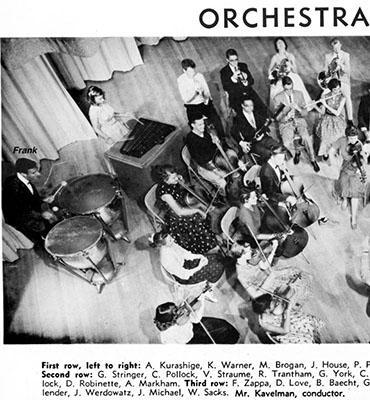

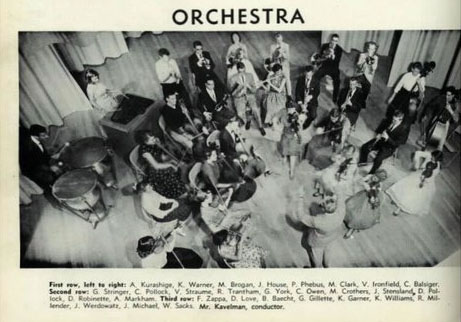

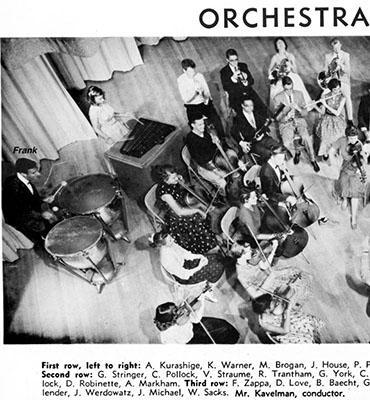

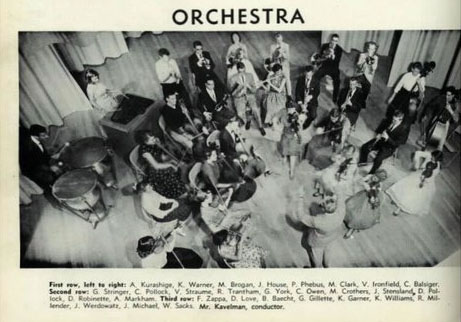

ORCHESTRA

First row, left to right: A. Kurashige, K. Warner, M. Brogan, J. House, P. Phebus, M. Clark, V. Ironfield, C. Balsiger. Second row: G. Stringer, C. Pollock, V. Straume, R. Trantham, G. York, C. Owen, M. Crothers, J. Sternland, D. Pollock, D. Robinette, A. Markham. Third row: F. Zappa, D. Love, B. Baecht, G. Gillette, K. Garner, K. Williams [Kenny Williams?], R. Millender, J. Werdowatz, J. Michael, W. Sacks. Mr. Kavelman, conductor. [p. 73]

Robert Kavelman

Band, Orchestra

BEACHCOMBER STAFF

Seated, left to right: D. Pressler, J. Busboom, Editor; Mrs. Martin, Sponsor. Standing: L. Houserman, N. Ninomiya, J. Jansen, M. Schaefer, J. Grayson, B. Gordon, S. Wilson, L. Littlefield. Back row: J. Hazel, G. LeFebvre, D. Butris, K. Wigginton, F. Zappa, P. Graves. [p. 89]

Although there is no record of future Rock 'n Roll Hall of Famer Frank Zappa participating in interscholastic athletics during his Mission Bay years, apparently he did exhibit an interest in an early Middle Eastern form of baseball, perhaps an off-shoot of seker-hemat. According to The Beachcomber (December 16, 1955), several students were asked how they planned to spend the upcoming New Year's Eve. Zappa replied, "Gonna get stoned."

This is the earliest year for which Frank Zappa appears in a high school yearbook, from the 1955-56 school year. Based on a variety of sources, he was in his very first musical group called the Ramblers and the pianist from the Ramblers (Stewart Congden [Congdon]) is shown in this book as a Junior.

There were a few teachers in school who really helped me out. Mr. Kavelman, the band instructor at Mission Bay High, gave me the answer to one of the burning musical questions of my youth. I came to him one day with a copy of "Angel in My Life"—my favorite R&B tune at the time. I couldn't understand why I loved that record so much, but I figured that, since he was a music teacher, maybe he knew.

"Listen to this," I said, "and tell me why I like it so much."

"Parallel fourths," he concluded.

He was the first person to tell me about twelve-tone music. It's not that he was a fan of it, but he did mention the fact that it existed, and I am grateful to him for that. I never would have heard Webern if it hadn't been for him.

I listened to the [Edgard Varèse] record and I liked it and I asked my music teacher in high school whether or not there were other composers who were writing material like this, and he gave me some other names.

One such little old lady had doing some work at her house for a couple weeks now. Her husband (Robert, a man in his 80's) is confined to a wheelchair and she (Elizabeth) is in her 70's but recovering from hip replacement surgery. [...] "Oh, Robert was Frank Zappa's band director when he taught at Mission Bay High School in California!" she says. She then produces a clipping from the Kalamazoo Gazette, Saturday, January 27, 2007 edition wherein Dave Person goes out and interviews Robert Kavelman about being mentioned in Zappa's autobiography. Apparently Zappa credits Robert with exposing him to twelve-tone music. I thought this was about the coolest thing i'd heard in a long time. I went inside and engaged Robert in conversation. He said when the interview started he didn't really know anything about Frank Zappa but as he went through his old school pictures and such was like, "Oh yeah! I remember that kid!" Robert's a real great old guy. . naturally curious about things still. He even showed me that he went out and got two books on Zappa to read up on his former student. One was the Zappa autobiography, and another was Zappa: A Biography by Barry Miles. Robert Kavelman is mentioned in both books!

When I was going to school in San Diego, at a place called Mission Bay High School, there was really popular local band functioning at that time called The Blue Notes which featured a guy called Wilbur Whitfield. And we were all very proud of Wilbur when he escaped from San Diego and went to Los Angeles to record ["P.B. Baby"] on the Aladdin label.

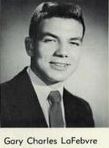

[Gary LeFebvre] attended Mission Bay High School, where he played in the marching band with fellow San Diegan Frank Zappa.

"Frank and I would sit down at the piano and trade 'weird chords'," LeFebvre recalled in a 2006 U-T San Diego interview. "My original goal was to be able to play music with anybody and not drag anybody down. I think I achieved that."

[FZ] was suspended from Mission Bay after he and a friend set off a stink bomb in a biology class, because they felt the teacher "was cruel to little animals."

The Ramblers

It's almost impossible to convey what the r and b scene was like in [San Diego]. There were gangs there, and every gang was loyal to a particular band. They weren't called groups, they were called bands. They were mostly Negro and Mexican, and they tried to get the baddest sound they could. It was very important not to sound like jazz. And there was a real oral tradition of music. Everybody played the same songs, with the same arrangements, and they tried to play as close as possible to the original record. But the thing was that half the time the guys in the band had never heard the record—somebody's older brother would own the record, and the kid would memorize it and teach it to everybody else. At one point all the bands in [San Diego] were playing the same arrangement of "Okey Dokey Stomp" by Clarence Gatemouth Brown. The amazing thing was that it sounded almost note for note like the record.

I didn't have an actual drum until I was 14 or 15, and all of my practicing had been done in my bedroom on the top of this bureau—which happened to be a nice piece of furniture at one time, but some perverted Italian had painted it green, and the top of it was all scabbed off from me beating it with the sticks. Finally my mother got me a drum and allowed me to practice out in the garage—just one snare drum. Then I entered my rock and roll career at 15 when I talked them into getting me a complete set, which was a kick drum, a rancid little hi-hat, a snare, one floor tom, and one 15" ride cymbal. The whole set cost 50 bucks. I played my first professional gig at a place called the Uptown Hall in San Diego, which was in the Hillcrest district at 40th and Mead. I remember it well, going to my first gig: I got over there, set up my drums, and noticed I had forgotten my only pair of sticks [laughs]. And I lived way on the other side of town. I was really hurting for an instrument in those days. For band rehearsals we used this guy Stuart's house. His father was a preacher, and he didn't have any interest in having a drum set in the house, but they allowed me to beat on a pair of pots that I held between my legs. And I'm sitting there trying to play shuffles on these two pots between my legs!

The first band I ever played in was a rhythm & blues band in San Diego called The Ramblers, and the leader of the band was Elwood Jr. Madeo.

The band was led by Elwood 'Junior' Madeo (known as 'Bomba The Jungle Boy' on account of his Italian/Indian background).

A friend of mine [had a] rhythm-and-blues band called the Ramblers, and he needed a drummer. I'd been playing drums in the high-school orchestra, so I talked my parents into buying me a set of used drums for fifty dollars. But I couldn't get delivery on the drums until the day of the show. The band rehearsed at the piano player's house. We borrowed all the pots and pans from the kitchen, and I put them between my legs like bongos and played a shuffle beat on them.

We used to go over to this Minister's house because his son was a piano player and I would sit in the living room with a pair of pots and a pair of sticks trying to get a shuffle going while Stewart Congden [Congdon], which was his name, was plonking away on the piano.

I had very little hand-to-foot coordination as I soon discovered in my first job as a drummer. I wanted to be in a Rock 'n' Roll band, and I twisted my parents' arms to get me a drumset. Up until then, I had been practicing to play in this band by putting two pots between my legs like bongos and playing with drumsticks, so I didn't really comprehend that you had to work your foot or anything. But I talked my parents into buying this drumset which they got second-hand from a guy up the street for 50 bucks. We got our first job at a place called the Uptown Hall, in the Hillcrest section of San Diego, and I took delivery on the kit right before the gig. You can imagine what happened, out there trying to play a Rhythm & Blues dance tune and not knowing how to play the kick.

By 1956 I was playing in a high school R&B band called the Ramblers. We used to rehearse in the living room of the piano player, Stuart Congdon—his Dad was a preacher. I practiced on pots and pans, held between my knees like bongos. I finally talked my folks into buying a real drum set (secondhand, from a guy up the street, for about fifty dollars). I didn't take delivery on the drum set until a week before our first gig. Since I had never learned to coordinate my hands and feet, I was not very good at keeping time with the kick-drum pedal.

The bandleader, Elwood "Junior" Madeo, had gotten us a job at a place called the Uptown Hall, at 40th and Mead in the Hillcrest district of San Diego. Our fee: seven dollars—for the whole band.

On the way to the gig, I realized that I had forgotten my drumsticks (my only pair), and we had to drive back across town to get them. Eventually I was fired because they said I played the cymbals too much.

I played one or two gigs with them, but I wasn't very good so they fired me.

Frank lands a spot with his first rock band, the Ramblers, in San Diego. They work places like American Legion Post No. 6.

I remember when my brother, Elwood Madeo, Jr. fired Frank Zappa. Frank was great but he did often play too loud then. The band's name was The Ramblers (not the Black Outs). It was the best teen band in town (San Diego), and won all the battles of the bands except one. I think they lost to the Velvetones at the Palladium when that band featured two female singers that night.

It took a while before Frank persuaded El to let him join the band. It was during our teens and it was the first band Frank ever played in. Most of the time, they practiced in our garage.

El plays lead guitar, formed and was the leader of the Ramblers. I think the battle they lost was in 1959 at the Shrine Auditorium instead of the Palladium, I was there but I cant remember which. I'll find out. Those were memorable days, we were all so young in many ways. Frank had a lot of respect for Junior as a guitarist. Years later Frank flew him from San Francisco to Los Angeles several times for album recording session.

Our repertoire consisted of early Little Richard stuff . . .

Charles Ulrich, August 15, 2014

The members of The Ramblers included:

Elwood Madeo (guitar) Stewart Congdon (piano) FZ (drums) Del Esquerra (tenor saxophone) Ralph Hensley (saxophone) Cookie Taylor (vocals) and a series of bass players

[Elwood Madeo] says he did not fire FZ. After FZ announced that he was moving to Lancaster (but before he actually moved), Madeo went ahead and hired a new drummer, Johnny Callard.

He didn't know Ronald H. Williams at Mission Bay High School. [...] He mentioned two rhythm guitarists, Joe Martin and Joe Hernandez.

I wasn't that great a drummer; I didn't have the coordination to really be that successful. [...] My favorite drummer at the time was Louie Bellson. I was amazed at what he did. Then I got into 'Philly' Joe Jones.

The San Diego Friends Through The Years (1954-1959)

From the following pictures, Stewart Congdon, Larry Littlefield, Jeff Harris and Elwood Madeo are known to have been at high school in San Diego with FZ. Most probably the Kenneth and Ronnie Williams in those pictures are not the infamous Kenny & Ronnie that FZ met in Ontario years later, but it's an interesting coincidence.

K. Williams—Junior [p. 44]

S. Congdon, L. Littlefield—Sophomores [p. 49]

Kenneth Roy Williams—Senior [p. 36]

Gary Charles LaFebvre

Joe D. Martin

Stewart Congdon—Junior [p. 48]

Larry Littlefield—Junior [p. 51]

Del Esquerra

J. Harris—Sophomore [p. 58]

Congdon, Howard Stewart—Senior [p. 20]

Littlefield, Larry Wayde—Senior [p. 30]

Delano Ramirez Esquerra

Harris, Jeff—Junior [p. 57]

Madeo, Elwood—Junior [p. 58]

Williams, Ronnie—Sophomore [p. 69]

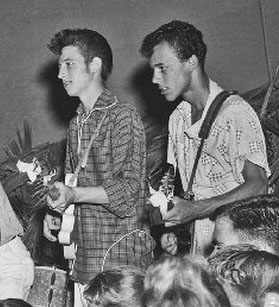

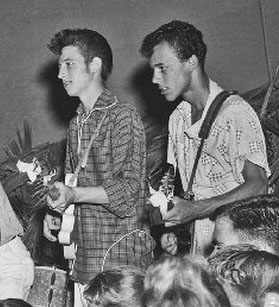

The Ramblers—Shipwreck Dance, April 12, 1957

Special thanks to Javier Al Fresco

[Elwood Madeo on the right.]

Harris, Jeff Todd—Senior [p. 31]

Madeo, Elwood Joseph Jr.—Senior [p. 37]

Williams, R.—Junior [p. 69]

Ralph Sherman Hensley

Ronald H. Williams—Senior [p. 55]

Additional informants: Tan Mitsugu, Javier Marcote (special thanks to Javier for finding and providing so much material)