Orchestral Stupidities

Vienna Symphony Orchestra, 1979

Hugh Fielder, "Zappa," Sounds, September 9, 1978

Earlier this year there was a report that you were going to write something for the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Is that going ahead?

No, they decided that they can't get the orchestra for the date that they wanted to do it. This is the piece here (points to a large black folder containing the full orchestral score for the work). I write on it all the time. I've got two movements finished and . . . well you can see what it takes to prepare the thing . . . after I've done my scribbles it has to go to a copyist who has to prepare the pages that look like this (flips through pages) and then from this they make the individual parts.

This is for a full orchestra?

A monster orchestra.

And any rock instruments?

No. Anyway, I've decided to keep working on it even though they can't arrange it for the date that we want to do it. It was supposed to be for next May. What I'll probably do is to finish the piece off and then hire an orchestra and record it.

It's an expensive proposition.

Well, some rock and roll musicians make a bunch of money and stick it up their noses. I stick mine in my ear.

Genesis: What about new projects? What's happening?

Zappa: Well, every time I tell people about what I'm working on, they want to know where it is. They don't realize how long it takes to do these things. Like one thing that I've been working on for a couple of years is another orchestra album. But it takes a long time to prepare the music and an even longer time to save up the money to do it. It's an expensive project. It takes about a quarter of a million to three hundred thousand dollars.

Genesis: How do you put an orchestra together for that kind of album?

Zappa: You can go to Hollywood and call a contractor and order forty-five strings and twelve brass and so on, and he gets out the list and calls all the guys who are available. They've never really played together, but they're good musicians and they all know each other. You put them together and rehearse them, and you come up with a performance. Or you can go to Europe and find an existing orchestra and try to find a hole in their schedule when they can take a two- or three-week period of time to rehearse, then tape it over there. I think this time I'll do it in Europe.

If you want to write enormous orchestra pieces, who's going to pay for it? Who's paying for the musicians? Who pays the copyists? I mean, so far on this project, [a planned Vienna Symphony concert which has since been cancelled] I have spent $44,000 on copying. That's what I've spent—just to get this far with the project, so I had scores in my hand to show those people in Vienna. Now I have more copying bills to get the parts for the orchestra. The copying has been going on for over two years.

[FZ] recently completed a group of ambitious orchestral works that were scheduled for a world premiere in Vienna until the project's primary financial backer, the Austrian television network, pulled out at the last minute. Five years in the making, the works were composed for a 120-piece orchestra, necessitating the employment of five copyists, two of whom had been involved in the process for five years, with a total copying investment of fifty thousand dollars. Another fifty thousand dollars was expended on telephone calls from the U.S. to Austria. Bound in black morocco, one piece, "Mo And Herb's Vacation," which Zappa described as "a dramatic, dissonant piece," comprises 83 pages of music.

[...] One of Zappa's top priorities is seeing his orchestral works performed properly. "The music is done and the parts are copied, so if an orchestra anywhere wanted to give a performance of it, and they would guarantee the right amount of rehearsal time and pay the fees that are involved in performing the music, it could happen again. But," he asserted, "I have no intention of just sitting and spending thousands of dollars to produce reams of wallpaper. I want to hear the music performed right. I don't want to have to go to the concert and sit there and be embarrassed by 120 people playing it wrong. No matter what the audience thought about it—even if they loved the fuck out of it—if the orchestra played it wrong, I'd be very upset."

FZ, interviewed by Michael Branton, BAM Magazine, October 5, 1979

What I really want to hear is that orchestra stuff I wrote for the Vienna Symphony, but that's too expensive. That program was cancelled because the Austrian television station [which had planned to broadcast the program] backed out of the deal.

But behind that has been another pet project stretching back two or three years—an extravagant orchestral score running to two weighty manuscript tomes titled "Mo 'n' Herb's Vacation", and "Wøööøl", "Bob in Dacron and Sad Jane". It would need, Zappa estimates, about 110 musicians, vast sums of money and a month of rehearsals, six hours a day, five days a week. Zappa has never heard it. It is one of the pieces that sprang from the brain and appeared on paper. Short sections of the percussion track have been played, but he admits one of the main reasons he would like to get it on-stage is purely to hear what it sounds like.

The score is immensely complex. Flipping through the pages, he plucked out one drum line which required the gyro brained skin-basher to play 13 notes in the time of two. The rest of the time signatures are equally as haywire.

"In order for it to happen money has to be invested by me to have the stuff printed up, buy ad space you've really got to run a mail-order business in order to sell this stuff. Those books represent a few years worth of work and the copying bills for the people who drew up these things to make it look neat like that was astronomical."

[...] Now he's considering hiring over 100 top musicians—they'll have to be first rate to cope with the ultra-complex score—plus a conductor. Zappa has someone in mind, Friedrich Cerha of Vienna, but isn't sure if he's free.

"He has the scores now and he's interested in doing it. We almost got a performance of this stuff together last year. Austrian Television was contributing one of the largest parts of the budget and at the last minute they dropped out. That left me holding the bag. I'd already advertised that it was coming up, the hall was booked, the orchestra was being provided by the City of Vienna, the conductor had the score—the works, and at the last minute we had to cancel it.

"Since then they've called me back three or four times and asked if I was still interested in it and I told them "I can't do business with you because you've cost me so much money already". There was 50,000 dollars in score-copying bills and approximately 50,000 dollars in telephone calls and transporting my manager all over Europe trying to raise the money for finishing the thing off, and that's a total loss."

Now he has been offered a contract with a guarantee that it will happen in the Summer of 1981, but he still wants it firmed up well beforehand.

The orchestration includes a drum kit, electric keyboard, and electric bass, but the rest is an orchestral monstrosity.

"I know a lot of people already who can play it without too much trouble, but the trick is getting them there all at once. Who pays? Who flies them from LA or New York to Vienna and pays for their food, hotel and salary for the duration of the rehearsals? I'm sure they have some good musicians in Vienna, but no-one is going to sight-read that, I can guarantee it. To get it together, some of that stuff in there requires some specialists playing. Because of the rhythmic writing, unless you have people who can play those funny kinds of rhythms and play them with conviction, the performance wouldn't sound right."

Several years ago . . . five maybe . . . the people who promote our rock shows in Vienna (Stimmung Der Welt) approached me with the idea of doing a concert in Vienna with the Vienna Symphony. I said okay. After two or three years of pooting around with the mechanics of the deal, work began on the final preparations. The concert was to be funded by the City of Vienna, the Austrian Radio, the Austrian Television, and a substantial investment from me (the cost of preparing the scores and parts).

At the point when the official announcement was made that the concert would take place (I think it was in June or July), there was no written contract with any of the governmental agencies listed above. As it turned out, the person from the Austrian TV who pledged $300,000 toward the budget (which was to cover three weeks of rehearsal, shipping of our band equipment, air fares and housing for band members, and band and crew salaries . . . I was not getting paid for any of this) did not really have the authority to do so and was informed by his boss that that amount had already been committed to other TV projects. This created a situation wherein the remaining sponsors still had their funds available, and wished to proceed, but somebody had to round up the missing $300,000 from another source.

At this point Bennett Glotzer, my manager, got on a plane to Europe and spent the best part of a month thrashing around the continent trying to raise the missing bucks. No luck. Between his travel, food, hotels and intercontinental phone calls and my investment in copyist fees to prepare the music (not to mention the two or three years I had spent writing it), the total amount I had spent in cash at the time the concert was cancelled came to around $135,000 . . . this is not funny unless you're Nelson Bunker Hunt.

A moving moment as the Master summons his bodyguard to fetch two gigantic mammoth format bound notebooks containing the complete orchestrations for guitar, percussion and 108-piece orchestra of 4 great works: Bob in Dacron, Sad Jane, Mo 'n' Herb's Vacation and VOOOOL, bravura pieces of uncertain fortunes. Sad Jane was to have been performed by the Vienna Philharmonic, conducted by Frank, but the project had to be abandoned for lack of funds (yet again), Austrian TV refusing to pay the rights asked for recording the event. Frank has since entrusted the whole thing to the person responsible for the CBS classical catalogue so that they could end up with Pierre Boulez. But it seems more likely now that the works will be put on by the London Symphony Orchestra. Watch this space . . .

Mark Lundahl, "Frank Zappa Remembers San Ber'dino," The Sun, Baltimore, April 7, 1980

Zappa has also finished composing another grand-scale orchestral work, "Bob in Dacron and Sad Jane," written for 120 pieces. However, he still is having trouble finding an orchestra to play this and his other recent instrumental pieces. The reason: Sheer expense.

"In a more gracious era it was not the composer's responsibility to work his ass off at a parttime job in order to pay for the privilege of hearing his music played. I find that just disgusting," Zappa said.

"Even if I could pay for it, that I would have to in order to hear it, that's an insult. I already did the hard part. I wrote it.

"The government should set enough money aside for the arts to the extent where it will help enough people. Right now it's dispensed by committees who give it to approved, clean sorts . . . you know the type."

Holland Festival, 1981

Frank is working out a deal with the Dutch government for a presentation of his orchestral music next summer. Originally Zappa had planned to work with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra for a television program, "and the Austrian television was supposed to put up $300,000. Then, at the last minute, they backed out. I said, 'You want me to put up $300,000 of my own money? Look, I already did the hard part, I wrote the stuff!'" The deal was called off, but not before the Dutch heard about it.

"They sent me a list of things they wanted to perform. They wanted 'Music for Low-Budget Orchestra,' they wanted 'Let Me Take You to the Beach,' 'Waka/Jawaka,' all the stuff from The Grand Wazoo, and I said, 'I'll fix you right up.'" And to sweeten things, "they may get a choir, and if they do we'll be able to do some of the things from 200 Motels."

What difference does Zappa make between writing for an orchestra and writing for a band?

"I approach it the same way. Some of the members of the band will play parts, and there are a couple of guitar solos which I'll do."

Last year in Amsterdam, the head of The Holland Festival came to my hotel and said they wanted to do a special performance of my orchestral music with The Residentie Orchestra (from The Hague), as well as performances of certain other smaller pieces by The Nederlands Wind Ensemble, all of these performances were to take place during one whole week of the festival. I told him that I had received several offers in the past (including one from the Oslo Philharmonic where they thought they might be able to squeeze in two days of rehearsal), and described the whole Vienna business in glowing terrns. I told him that it would be nice to have the music performed, but, since there was a lot of it, and it was difficult stuff, there was no way I would discuss it any further without the guarantee of a minimum of three weeks rehearsal, and in no way was I interested in spending any more of my own money on projects such as this.

He assured me that they were committed to doing the project, and that the rehearsal schedule could be arranged, and not only that . . . they were willing to pay for the WHOLE THING. The Holland Festival put up the equivalent of $500,000 for the event. Deals were then made with CBS to record and release the music, more copyists were hired, musicians from the U.S. who were going to play the amplified parts of the score were hired, road crew people who would handle the P.A. equipment (as the concert was to be held in an 8,000 seat hall) were hired, and a rock tour of Europe was booked (to help pay the cost of shipping the equipment and the salaries of the U.S. people involved . . . again, I was not getting paid), all in preparation for another summer orchestral concert that was doomed like the other one.

What happened? Well, first, let's understand the economics of a project like this. It involves a lot of musicians and they all like to get paid (this is a mild way of putting it). Also, since it was to be an amplified concert, there is the problem of special equipment to make the sound as clear as possible in the hall (it was called "THE AHOY" . . . a charming sort of Dutch indoor bicycle racing arena with a concrete floor and a banked wooden track all around the room). Also there was going to be a recording of the music, necessitating the expenditure of even more money for the rental of the equipment, engineer's salary, travel expense, etc., etc.

After making a deal wıth CBS to cover expenses that the Dutch government wouldn't, a new problem arose that became insourmountable—the needs of the U.S. musicians. Despite earnings of $15.000 for 17 weeks in Europe, all expenses paid, a few of these musicians ["Vinnie Colaiuta and Jeff Berlin," FZ, TRFZB, p. 149] called our office shortly before the start of U.S. rehearsals and tried to make secret deals to get their salaries raised and "Don't tell the other guys . . ."

When I heard of this, I cancelled the usage of the electric group with the orchestra, saving myself a lot of time and trouble rehearsing them, and a lot of money moving them around. Plans remained in effect for the orchestral concerts to continue as acoustic events in smaller halls. The recording plans remained the same also . . . five days of recording following the live performances.

About a week or so after the attempted hijack by the U.S. musicians, our office received a letter from the head of the Residentie Orchestra. Among other things, it mentioned that the orchestra committee (a group of players that represents the orchestra members in discussions with the orchestra management) had hired a lawyer and were ready to begin negotiations to determine how much of a royalty they would get for making a record. Since I had already raised the funds from CBS to pay them the necessary recording scale for doing this work, such a demand seemed to be totally out of line with reality, as I had never heard of a situation wherein an orchestra demanded that the composer pay them royalties for their performance of works he had written, nor did I feel it would have been advisable to set a dangerous precedent that might affect the livelihood of other composers by acceding to the wishes of this greedy bunch of mechanics.

A short time after that, the orchestra manager and the guy we originally talked to from the Holland Festival flew to Los Angeles for a meeting to go over final details. They arrived at my house about midnight. By about 1:30 AM, I had told them that I never wished to see their mercenary little ensemble and that permission to perform any of my works would not be granted to them under any circumstances. They left soon after that.

It was determined shortly thereafter that the cost of going through all of this inter-continental hoo-hah had brought my "serious music investment" to about $250,000, and I still hadn't heard a note of it.

CDK: You sent me this letter about the HOLLAND FESTIVAL . . .

FZ: The reason why the people from that particular orchestra give out wrong information about it is because they don't wanna let people know how fucked they are, and that they have to cover it up to let it look like something other than what it was. It was a case of pure union greed, just like in the USA or in any country where unions think they're fantastic . . . FUCK UNIONS is what I got to say.

Eric van den Berg, interview with Gail Zappa, de Volkskrant, June 8, 2000 (translation by Corne van Hooijdonk)

In 1980 Frank had a fight about an extra payment to the Residence Orchestra and withdrew his cooperation for a Zappa-week. Never ever would a Dutch orchestra play Zappa's music, was what he promised to put in his last will.

Looking For The Ideal Orchestra, 1981-1982

FZ, interviewed by Dave Benson & Dave Alpert, WMET-FM, Chicago, IL, June 28, 1981

As a matter of fact I just finished a little trip to Buffalo, where Buffalo Symphony played some of my material, we had a discussion—it was just a rehearsal—and we had discussions about them doing a performance of the material some time next summer.

And we've also been in negotiation with the Chicago Symphony—they were interested, they requested scores, the scores have been sent to them. I haven't heard from them yet whether or not they're interested in playing it.

Wanna know why we didn't do this thing in the United States? Besides the bad attitude we encountered, it was a money situation. We were originally going to record this with the Syracuse Orchestra with Christopher Keene conducting, and it was going to be premiered at Lincoln Center in New York City. We had made a deal with the Syracuse Orchestra and within a matter of days they managed to double the price. It started out at $150,000 for the whole project and then somebody in the orchestra union had found a whole bunch of extra rules that brought the cost up to $300,000. So I said no way.

Well, as soon as we got this extortionary message from the Syracuse Orchestra we decided to try to contact a British orchestra. First we called the BBC Orchestra but they were booked solid for the next five years. Then we called the LSO and they said, "Well, we don't know whether we can do it because we're just finishing off a film score and the musicians have one week off before they have to do another film score." And since they get to vote on everything they want to do, they put it to the orchestra and the orchestra members chose to record my stuff rather than take a vacation. They went directly from Return Of The Jedi to my stuff to another film. We had just a certain number of days to do the whole thing, and they were rehearsing their butts off. We had 30 hours of rehearsal for one concert and three days to record. [...]

I went to Mexico City and actually conducted their orchestra for a little while. They were very interested in doing the project, then after we had the rehearsal and we got down to what it would cost, the guy I dealt with added it up and wanted $400,000. He had somehow gotten a hold of what the scale would have been if I had done it in New York City. And there was no way that they were as good as the New York Philharmonic and no way that I was gonna give them $400,000 . . . so I said, "Thank you, goodbye."

As far as the Krakow Orchestra goes, they had been after me for years and at one point last August, right at the end of a European tour, I was supposed to go from Sicily to Warsaw to start this project. It had all been set up at the beginning of the tour. Two weeks into the tour, martial law broke out in Poland and all this other crap was happening over there. So I said, "I don't think I want to take my recording truck into Poland next to the tanks. It's crazy to do that." So we passed.

After the Holland deal bit the dust, there was another one . . . in Poland . . . actually, two different orchestras in Poland—and always the same result: NO MUSIC—LARGE EXPENSE. Anyway, finally I said: "These European orchestras are a pain in the ass."

Most of the projects were situations in which a governmental agency was involved —the government of the municipality or the country, whatever it was—situations in which 'official guys' had originally suggested the project, and were supposedly going to be responsible for paying for it.

That's when I decided to just go ahead, pay for it all myself and do it with A Real American Orchestra.

We made a deal with the Syracuse Symphony. We booked a concert date (January 30, 1983) at Lincoln Center. The music was going to be played and recorded in the United States.

Well, somehow, AFTER the deal was made, somebody in the Syracuse Symphony 'upper echelon' decided to DOUBLE the agreed-upon price by whipping out an assortment of semi-obscure 'local union regulations.' Syracuse priced themselves out of the market.

So I said—actually, by this time, I'm screaming—"Fuck this! I'm not going to get bent over by some deranged American union extortionist!"— and that's when I decided to rent the BBC Orchestra (or the equivalent) in England. We called the BBC Orchestra. They were booked for the next five years.

They would have been a good orchestra to do it because they specialize in contemporary repertoire, BUT they weren't available. So, we called the LSO—and, at first, THEY weren't available either.

They were just finishing a film score and had planned a two-week vacation for themselves, after which they were going to start on ANOTHER film score.

The way the LSO works is, it's owned by the musicians—it's a 'cooperative.' THEY decide who's going to be their conductor and what work they're going to do. When my project was suggested to them, they voted to do it rather than take a vacation, so I went ahead. We rehearsed thirty hours, did one live concert, and then did the recording.

The LSO Project

There's no amplified instruments on there. It's all acoustic. That's

just what the music was supposed to be. It wasn't supposed to be an

electric band backed up by the London Symphony Orchestra. [...]

The

problem is, any time somebody from rock and roll does anything with an

orchestra, it's polluted by the rip-off type stuff that's been done in

the past you know, with three or four guys playing fuzztone crap while

the whole orchestra plays whole notes in the background, and then every

18 bars goes da da to daaah! Everybody has this picture of rock

and roll vs. symphonic-fusion stuff. I didn't want to have anything to

do with that. That's not what the intent of the album was.

Can you tell the whole story of the LSO?

The LSO's kind of an interesting story in itself, because basically, if you every had the chance, and maybe you hadn't or you had, if you never had a chance to go around Frank's house and his basement, the basement connected to the— the regular house went through a basement, which we had a little film editing room in, and then we had a fireplace in there, with a guitar that Jimi Hendrix gave him, hanging up, which is kind of the mascot of the studio. You walk through that into the other studio. Well, in different corners, you would see stacks of sheet music. I mean stacked like three feet high. Huge stacks of sheet music. And they were all over the place. And I started asking him, "Frank," soon after I got there, I said, "Frank, what are these things?" He said, "Oh, just something I've been writing." It was his classical music that he was writing, and he was real serious about it. And because he was real serious about it, he didn't really talk about it a lot. So I kind of worked on him as a friend. I just kind of said, "How long you been writing this stuff?" He said, "Oh, 13, 14 years." He'd been working on it a real long time. And it was always his dream to record classical music. When we got our out-of-court settlement, with Warner Bros, we got a $12.5 million out-of-court settlement . . .

This is a resolution of the whole . . .

Of the five-and-a-half years of the whole Warner Bros thing, so he had a good chunk of money. So I said, "Frank, now that you got some money, why don't we record some of your classical stuff? Because we can afford it, right?" He said, "No." He kind of just didn't want to do it. We hemmed around like this for months and months, and just never— and then finally one day I said— I started every angle I could. You know how you would with friends? You'd go, "What do you gotta do, you gotta die first, and then somebody's gotta take the transcripts." You know what I mean. You just try every angle you can, because you realize that he was very sensitive about this stuff. It wasn't like another sarcasm album, like he was famous for doing. This was something that he took more personal, and I think he was afraid people might laugh at him.

He'd already done the Orchestral Favorites album.

Right. He'd done Orchestral Favorites, but this adventure was a little bit different, because even then, there was a sort of satire in that, if you think about it. All the stuff he did with "Billy The Mountain." Orchestral Favorites itself had a kind of a twist. That was kind of like his tribute to Varèse. His version of that. Where this other stuff here was just a little bit more of a serious tone. He was writing it more from a inside thing. He would be around his piano writing, and nobody could disturb him when he wrote. Not even his son, not his wife, not a telephone call, not me, not anybody. Nobody could walk in that room when he was writing that stuff. And he would chart stuff out. You just did not interrupt him at all. He would finish his train of thought, and get it all on paper. At any rate, to try to make a shorter story out of all this, because all this stuff is so long and detailed, he started trying out some different symphonies. We tried out the Mexican Symphony, and they didn't seem to be really very good. And Frank's dream was to do the Berlin Symphony. The real reason we had so many channels on the recording truck is that he had written— most of his stuff was written for 132 pieces. His whole ensembles were written— so what it all boiled down to is, we had a chance to do the London Symphony Orchestra, and it was only 107 pieces. And Frank had to condense down the writing, of course, he had to convert the writing down, and I had to go find a recording truck, because we didn't have enough time to bring our truck over there. Which was a real, it was a real sharp pain for me. I had to go over and use a Helios truck. But we made a deal with them, and we [end of side]

. . . so he got on with the manager, which had been Bennett Glotzer, and they basically fired the engineer. And Frank came into the control room and he said, "By the way, you're now the engineer for this whole project." I said, "Gee, Frank, thanks. But why are you doing that?" He said, "The guy never even heard of a PZM microphone." That's basically was his comment to me. He said, "There's no way I can work with an idiot like this guy I just talked to on the phone."

Kent Nagano

Kent Nagano, "Premiering Zappa with the London Symphony Orchestra," Zappa!, 1992, p. 8-11

I was on Paris at IRCAM, which is run by Pierre Boulez, and what really stuck out on the project list was Frank Zappa's name involved in a concert and recording [The Perfect Stranger]. I was so surprised that he was not only an icon of popular and rock music, but also had captured the interest of such people as Boulez and the Ensemble Intercontemporain. So when I came back to California, I contacted—among other people—Don Menn and asked how I could get in touch with Frank, because I wanted to see his music myself. I was put in touch with his office, which informed me that he would be visiting my area shortly on tour, and if I was really interested they would send me up some scores. The scores never came, but Frank did. He phoned to introduce himself and explain that he'd heard I was interested in his music. He had some scores with him, which he would be happy to show me, but he didn't have time to deliver them: I would have to come to his concert and look at them.

Being a classical music student, I was pretty nervous about setting foot in a jam-packed theater full of impressive electronic equipment and amplifiers so tall they seemed like skyscrapers. I was even more nervous when Frank's bodyguard escorted me downstairs to a dressing room, and there I met Frank Zappa. He brought out some of his scores. I looked at them and realized they were far too complicated for me to comprehend just sitting there. I asked if I could study them a little more. Frank said, "Sure, go on, hold on to them as long as you want." And so, after watching a very interesting and complicated rock show complete with choreography and conducting, I left with the scores under my arm. [...]

I asked Frank if I could perform some of his music with the Berkeley Symphony. I thought it would be challenging for the musicians and interesting for our audiences, and we might actually serve the purpose of opening the window for the world to see what sort of compositions he had outside of the rock ensemble setting. One thing let to another, and Frank decided to have a huge project that would include a public performance of his works and a recording of these very large orchestral pieces. The London Symphony Orchestra was chosen, and the conductor selected was me, a choice that was totally unsolicited and a complete surprise to me. Frank Zappa is capable of choosing whomever he wants to work with. It certainly wasn't necessary at all for him to choose me. I had just had that one brief meeting with him in Berkeley, and had only spoken to him a few times over the telephone. But, of course, being chosen was a tremendous privilege, honor, and opportunity. I found out two years ago that he had done pretty detailed research on my work. He had called a lot of my colleagues—composers, conductors, and players in the various symphonies—to find out if I had any talent.

When I was working with this orchestra that didn't have any money (laugh) and didn't have any audience, I mention that it was really important to work very hard and fast and quickly, be efficient and my reputation was spreading by word of mouth of someone who had ears, could hear and good sense of precession for complex scores. So when Zappa was looking for a conductor for his music, which is extremely difficult, it's one of the most difficult music to count that's been written. The only thing comparable that will beat it, perhaps a very complex Elliot Carter score or Takahashi's music or perhaps some of Pierre Boulez' music, I mean it's mathematically how to count out the rhythms, it's extremely difficult and technically.. it's exercises the parts of instruments ranges that's not very easy to play, quite virtual (some writing). And large orchestras, complicated passages where You really have to have a good control of basic rhythm technic to help guide a orchestra through it. Unknown to me if Frank was doing some research to find out who could actually conduct his music. He had at that moment, just had a huge tremendous commercial success with one of his records and he wanted to realize a dream of his that he always had, which is to hear his symphonic scores played by one of the worlds great ensemble so that he actually could hear what it sounds alike instead of being massacred by.. by an orchestra that wasn't properly rehearsed. So he wanted the best orchestra that he could find and he wanted a conductor that could actually deal with it. And .. I've had heard of his music because I was visiting Mr. Boulez in the Institute of Research eh .. IRCAM at Georges Pompidou Center and I saw on the bulletin board "feature commissions" and on the list of composers who have been invited to write for Boulez and IRCAM was Frank Zappa's name and I couldn't believe it. You know I mean, this was for me a relic of the 1960:s. So I asked my friend of who worked there: what's the story with this Frank Zappa commission. He explained to me that there was a project that Pierre Boulez was going to conduct a concert of all Frank Zappa pieces and record them. And I thought God this is crazy, so I got in touch with Frank Zappa's manager and I said I like to see some of his scores but I never.. I never really heard anything for a long time until one day I just got a telephone call, it was from Frank Zappa, inviting me to come to one of his concerts. And he will give me some scores.

So I never in my life been to a rock concert before (laugh), having lived a very sheltered life as a classical musician, though I went out and bought some earplugs and went to this rock concert. And it was everything that I have feared. It was smokey and sort of light shows all over the place, crowded with thousands of people, dressed in very unusual clothing (laugh). During the intermission, this enormous bodyguard found me where I was sitting in the seats. He was so big, he looked lie a sumo wrestler and said "follow me" and of course I didn't argue and I followed him and he took me downstairs to the dressingroom. And there I met Frank Zappa. He was taking his intermission break and he showed me the score's he brought with him. He said, take a look at that, what do You think? And I open up the score's and they were really, as I said, so complicated that.. I was a bit taken aback and I didn't know what to make of them so I explained to him that I really didn't know what to make out of the score's. I had to take them home and study them a little bit before I could answer him. He said okay, he said take the score's, go home and let me know what You think. So I studied the scores and I had a great time because they were so complicated. They were challenging to figure out. And I found in my great surprise that in this stack of scores was some pieces that were really great, really exciting wonderful pieces. That, not only were it's complex but they were.. they were well written compositions.

And few weeks went by and I got a telephone call from Frank Zappa, again announced out of the blue, said: well, what do You think, Would You be interested in the scores. And I said: well yes, I'm really interested in a couple of scores and I would like to perform them. He said: how would You like to come with me. I've hired the London Symphony Orchestra, how would You like to come with me to London and record these pieces, do public concerts in London and record them? And at this point I was really unknown, I was just basically out of school and I was working with this orchestra that's having a tough time. This is one of the very few times in my life when I tried to be coy (laugh), cause I want to be cool. So, of course I wanted to go, and I liked the music a lot, but I said: well gee, I don't know. I have to think about it, and of course that was being dishonest. But I said it anyway and Frank said: hmm, well I tell You what. I'll give You fifteen seconds to think about it, and after fifteen seconds You either say yes or no and if You don't say anything at all, I'll just go to another conductor. So I said: well actually Mr. Zappa I am.. I am interested (laugh) and that was the last time that I actually ever tried to be coy. Because when You're dealing with people who are really serious, there's really no room to play games. I mean people who are really concerned about making music, just want to make good music, so in a way he taught me a lesson very early on in my career.

And it was a wonderful experience. Frank Zappa is a great musician. He has ears that can hear things that are just phenomenal. Extremely complex textures and we founded partnership because they were... I could call a lot of wrong notes but actually so could he. He could hear this incredibly complex orchestrations and identify what wasn't working right. And because of that, he earned my great respect. Oftentimes a composer doesn't even know what he's written and then... I can't be serious about his music if the composer is not serious. He earned my respect and the London Symphony's respect. They stood up and gave him a standing ovation after the public concert. And we produced three albums during that period and that was my introduction to the London Symphony, a group whom I still serve today as principal guest conductor. It's a funny way to make the acquaintance of an orchestra but I suppose You have to started somewhere (laugh) and so now, twelve years later we were a lot together and record a lot together.

When I heard that Frank Zappa had been commissioned to write some pieces for Pierre Boulez, I was really curious, because that's one of the biggest honors a composer can possibly get—to have Boulez ask you to write a piece for his ensemble.

So I contacted Frank's management and met with him backstage when he played the Berkeley Community Theater, late in 1981. He showed me a score and said, "This is what I do." So I sat there and looked at it, and it was just an amazing score. It was not some thing that I could just sit and casually glance over. Very, very sophisticated stuff; I couldn't even hear it—I had to take it home and look at it at the piano. He let me borrow it to study and gave me a couple of other ones. It took me a long time just to get through it. Bear in mind, I'm one of those overly educated erudite jerks—heavy theory background. I was very excited by it. For someone like me, who peruses—without exaggeration—maybe 50 or 60 brand new scores a year, it was so refreshing to see a very finely crafted score like that. So I called Frank and explained that I'd like to perform the piece. His answer, which now I realize is typical but at the time sort of took me aback, was, "What makes you think you can play the piece?"

We had a meeting about it, but the main issue was being able to pull together enough rehearsal time to do it properly, which is a very expensive venture. The music is so difficult it requires maybe five times the normal amount of rehearsal, so if you're working with a union orchestra it means big dollars. But then Frank called me with the invitation to go to London.

Nagano came to see Frank Zappa backstage during a 1981 Zappa tour, and mentioned some pieces he had heard Zappa had been working on, which hadn't been performed. Zappa was reluctant to pull them out and rework them, but Nagano's perseverance apparently convinced him. Nagano calls Zappa's scores "phenomenal." The two started working together on the four pieces—Bob in Dacron/Sad Jane, Mo 'n Herb's Vacation, Sinister Footwear, and Pedro's Dowry—and soon afterwards Nagano led the London Symphony Orchestra for the recording. The Berkeley Symphony's "Zappa Affair" marked the first performance In the United States.

Kent Nagano with Inge Kloepfer, Classical Music: Expect The Unexpected, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2019, p. 131-132

I still remember that my parents forbade Zappa's music in our house after watching one of his concerts on TV. In their opinion, Zappa was absolutely not for children. I discovered Zappa in the late seventies on a first short trip to Paris. Pierre Boulez wanted to perform several of Zappa's works with the Ensemble intercontemporain. It aroused my interest. I marveled.

At home in California, I decided to contact his manager so I could take a look at some of his scores. But for a very long time, I did not get any response to the message I had left. Then, all of a sudden, out of nowhere, Zappa himself called me. He first wanted to know what my interest in his compositions was based on. Then he invited me to one of his concerts, which was to take place in Berkeley. He wanted to meet me there and show me some of his scores.

Even as an adult, I had never in my life been to a rock concert. As a classical music artist I had grown up quite sheltered. Rock concerts were out of the question. The concert in Berkeley was a completely new experience for me, a mass event, teeming with thousands of people. One lightshow after the other, endless smoking—it was all entirely unfamiliar to me. During the break one of his gigantic bodyguards, named Big John, came up to me, ordered me to follow him and brought me to the superstar's dressing room.

There he sat, Frank Zappa, admired, controversial and as a symphonic composer by and large unknown. he was eating caviar with sour cream. After a short exchange, he handed me quite a number of his scores. I took a look and found some unbelievably complex orchestral music that I was barely able to evaluate at first glance. He let me take the scores home. I wanted to look at them more closely there. Given their complexity, it turned into a quite a challenge, to be honest. I was completely surprised to find incredible passages of serious music on many of those sheets of music, exciting, excellently written, tremendously colorful. I had his music in my head for days. However, I didn't hear from Zappa for weeks. I had neither his phone number nor his address, and thus no way of contacting him.

Then, suddenly, and again completely out of noweher, he called me. "And," he asked, "what do you make of it all?" He wanted me to visit him at his home, so we fixed a date and time and he collected me from the airport, but then we didn't drive to his place after all; instead, we went straight to the university campus. There he had hired an orchestra, with whom I was meant to rehearse several of his works—as a trial run, so to speak. I caught my breath, yet I had no choice but to comply. After a lengthy rehearsal we drove to his home. There he told me about his big dream. One day, he wanted to have his symphonic works performed. This was why he had started looking for an orchestra and a conductor who could make his dream come true. I left deeply impressed with the seriousness of his request.

A few days later again, I received another call from him. Quite abruptly, he asked me this time if I wanted to accompany him to London to record his music with the London Symphony Orchestra. At that time, I was not yet particularly well know as a conductor—and I hesitated. A little too nonchalant, I told him I would think about it. Frank's response was both a shock and an impressive lesson about the intransigence of great artists: "I give you exactly fifteen seconds to say either yes or no," he replied calmly. "You have to decide now. If you say nothing at all, I'll hang up and find myself a different conductor." After less than fifteen seconds I said yes—accompanied by a feeling of deep shame for having hesitated, and not giving a straight answer to an artist who cared so deeply about his art. Those who really mean it seriously do not make a fuss and do not play games. That was a lesson I learned from Zappa.

Here's a moment I remember clearly. It was the first rehearsal, maybe halfway through. I was standing behind the basses, listening. During a short break, one of the bass players turned around and asked me what the conductor's name was. I told him, and the player said "he's very clear." And he was very clear. He was a young hotshot. As I mentioned, the LSO hired him later one—so that bass player wasn't the only one in the orchestra who was impressed.

The Recording Sessions

The LSO session was largely paid for by Valley Girl profits.

FZ, notes for LSO Vol. II

Rock journalists (especially the British ones) who have complained about the "coldness," the "attempts at perfection," and missing "human elements" in JAZZ FROM HELL should find L.S.O. Volume II a real treat. It is infested with wrong notes and out-of-tune passages. I postponed its release for several years, hoping that a digital technologist somewhere might develop a piece of machinery powerful enough to conceal the evils lurking on the master tapes. Since 1983 there have been a few advances, but nothing sophisticated enough to remove "human elements" like the out-of-tune trumpets in 'STRICTLY GENTEEL,' or the lack of rhythmic coordination elsewhere.

The rehearsals were from January 7th 1983 and before that we had the last 5 sessions on a film called Krull with James Horner, so there is no truth in the holiday change idea. In fact, in those days the orchestra didn't have a fixed holiday period (although we do now) and each player took time off at a time to suit themselves, with very little pay.

Most of us saw the music on the day we started. There was a Principal Flute on trial who eventually got the position and the way he coped with Zappa's intricate rhythms helped him make his mark. Usually with such music when the composer comes from abroad they bring the music with them so it's only available at the last minute. First reactions were, Oh My God! Lots of practising ensued I can assure you! London musicians are known as the fastest in the world at sorting out music but I can assure you we were pushed to the limits that week

The music was considered to be extremely complex. Lots of 11's, 15's, 17's, 19's etc, all against each other—which in real terms would have been impossible to play. It was a really difficult few days, I remember. We were rehearsed in Abbey Road and did the recordings down in some TV studios in Twickenham and a young conductor called Kent Nagano was brought in as he had a fantastic reputation in California for coping with modern music and had worked with Zappa in California! He, of course, went on to a permanent relationship with us becoming our Associate Guest Conductor for many years (in the 90's) and became the Halle's Principal Conductor.

[FZ] threw a champagne or drinks party at the end so he couldn't have been that unhappy!

There were 12 extra rehearsals before the concert day running from Jan 7-10, with a Barbican concert on the 11th January. I can't think of any other project that has had anywhere near that many rehearsals! We then had 6 sessions in Twickenham after all this so it was given an extraordinary amount of time.

The timpanist gave me a 1-hour lesson that was the most insightful ever regarding the physical action of a drumhead and tuning. I walked out of that understanding even more that I am not a real-serious timpanist. The brass players were sceptical—just not completely committed to the whole idea. Frank and Mark Pinske had developed (and were experimenting with) really wild and unorthodox mic'ing methods, and had constructed these weird mic'd glass panels that were looming over people's heads. But it sounded great, considering the recordings were made on an early digital machine. The orchestra was NOT used to playing music that was so difficult and that required homework—and there was some grumbling which of course made Frank irate because he was, after all, paying them. It did feel strange at first playing some of the band music with the LSO (like 'Strictly Genteel')—we were all used to it being so BIG. But what a great orchestra, and in the end I think that Frank was happy too.

ZappaPZM, Zappateers.com, April 24, 2011

In 1982 I was working for Ken Wahrenbrock developing and selling Pressure Zone Microphones (PZMs) when I received a call from Tom "Coach" Ehle at Frank's studio. Frank was finally going to be recording his orchestral compositions and he wanted to use Pressure Zone Microphones to record the London Symphony Orchestra. I agreed to go to the UMRK and was given the address in the Hollywood Hills. Frank was familiar with the flat plate version of the PZM and invited us into his living room to watch the Dub Room Video which has him wearing one on his forehead. We had been developing different baffle configurations for use with the San Diego Symphony and other live stage productions. Frank became very excited and started to make plans as to what to use to record the different instruments. I made arrangements with Crown, who was manufacturing the PZMs, to provide 60 of the capsules which we mounted in custom made baffles to fit Frank's requirements. Frank took them to London, did the recording and when he returned he invited Ken and me to the studio to hear the recordings.

Like to solve problems? Consider these. Arrive in London to record a music project that has been developing since 1975. The leased hall for the recording with the London Symphony (107 musicians) is too small. An immovable motion picture screen about eight feet from the rear wall (which the leasing agent forgot to mention) makes the room even smaller. It is also too noisy, and all the other major concert halls are booked.

Frank Zappa faced this as he arrived last January in London to record the ballet music he had been composing for the last eight years. He finally found space in Twickenham Studios, using a sound stage where the "007" movies had been shot. It was rather dead, which made it difficult for the orchestra but provided dry tracks for better mixdown and final editing. The music was also presented at a live concert at the [Barbican]. [...]

As he prepared for this project, Frank had Thom Ehle, one of his engineers, contact Vince Motel of Wahrenbrock Sound to check out some new prototype PZMs. Vince took several models to The Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, their recording studio. Frank and Mark Pinske, his recording engineer, tested them and wanted to explore PZMicrophony more. [...]

Frank chose to take many of the traditional microphones with him also and had arranged for the remote recording van to have many of them available, including a Calrec Soundfield mike. As they prepared for the recording session, Mark had 90 minutes to place the microphones after the stage crew placed the stands and chairs. He set up the microphones as they had planned with PZMs for strings and some percussion, and regular mikes for many of the instruments were set up in the usual way. As the rehearsal started and he checked each mike on the "solo buss," he found such vast differences in pickup quality that at each break he was scrambling to replace as many other mikes as he could with PZMs.

Due to the nature of the acoustics in the new venue and the size of the orchestra, PZMs became the overwhelming choice for this job. Because there were not quite enough PZMs available to use them exclusively, a few AKG 451s and an RCA ribbon mike were left in the setup. The hall, the musicians, the timing, all demanded a quality of microphone pickup that would lay down tracks for extensive editing work with little loss of quality and minimum noise and leakage. According to Zappa, this record could not have been made without PZMs, the Sony PCM 24-track digital recorder and the Lexicon programmable reverb unit. The recording studio in London turned out to be very dry and the Lexicon unit added the needed richness. And the thousands of edits for the final mix were humanly possible, Zappa says, only because of the outstanding features of the Sony recorder.

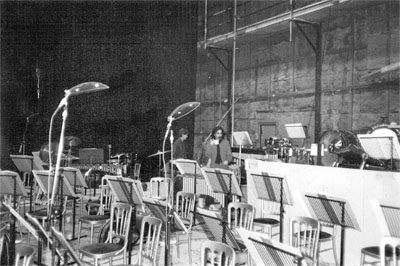

Frank Zappa during rehearsal break during the recording with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Kent Nagano, in January 1983. Picture by Karl Dallas.

Those recordings have no overdubs that I'm aware of. Everything was recorded in one big airplane-hanger studio. The whole orchestra took up only half of it. It was a big orchestra—with (as I remember) 9 percussionists (including Chad and Ed). The recordings were made in a sound truck parked outside. There were miles of cable, each section was miked every which way with PZM mikes attached to strangely shaped plexiglas baffles. Each section was recorded to a separate digital track—so it's no surprise that the recording sound have a kind of studio over-dub sound to it.

To the best of my recollection, every note in the score was recorded. The recordings were made to multi-track tape—probably 24 tracks, but I don't remember exactly. In the sessions, a great deal of effort went into acoustically isolating different sections. The orchestra was somewhat spread out but, unlike the concert, seating was pretty much standard orchestra layout. And there was those plexiglass baffles on the microphones that were supposed to increase the isolation.

Afterwards, Frank wasn't completely happy with the recordings (sometimes actually disappointed). I know he spent a lot of time trying to improve them in the mix. I remember him complaining that Kent's tempos varied from take to take, making it hard for him to splice. So the most likely explanation for parts disappearing from the released recording is that for some reason Frank decided to remove them. I doubt Kent had any input at all once the recordings were finished. About mallet parts not making it into the recording—one of Frank's orchestration tricks was to double a difficult wind or string line with some "precise" instrument (meaning one that has a sharp clear attack, like xylophone). The doubling instruments were supposed to blend into one sound, of course. The fact that he took those out of the mix implies the blend wasn't working for some reason.

Why drumset parts appeared on the recording that aren't in the score, I don't know.

It wasn't that the performances were bad it was more about—the way Frank put it—107 people all playing the parts right at the same time. Frank originally wrote many of his charts for another orchestra of 132 pieces (the Berlin Symphony Orchestra), so he had to condense it down to 107 pieces, which is all that the LSO had. He wanted to get the songs mixed with as many of the parts as he wrote them. So, a lot of edits.