Jello Biafra

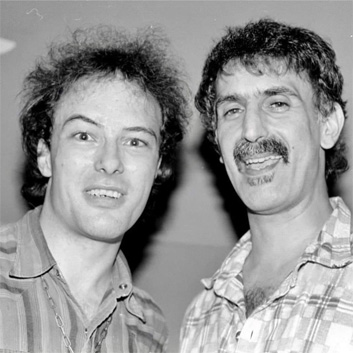

[Jello Biafra, FZ.]

Dead Kennedys Band Info, AlternativeTentacles.com

Biafra stumbled upon a reproduction of a painting by European artist H.R. Giger titled "Landscape No. 20: Where We Are Coming From." The painting, which features dismembered, ugly genitals copulating in what looks like sludge, had been reproduced in many books and magazines over the years, and Biafra secured the rights to include it as part of the Frankenchrist package. About the painting, Biafra says "I began to realize, 'My god, we have met the enemy and it is us, this is what we do to each other every day in consumer-oriented society. Wait a minute, this is what we're talking about on a lot of the Frankenchrist songs.' I thought the Giger painting would be a great way to drive home the point, even if some people in high positions of power with no sense of humor didn't seem to understand."

Originally, the painting was meant to be the gatefold inner cover for Frankenchrist, but a member of DKs vehemently objected and it was instead inserted into the album as a poster. Although the poster was expected to raise some eyebrows, no one expected it to cause as much trouble as it did. A warning sticker, albeit a sarcastic one, was affixed to the cover, partially to parody the warning stickers that the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) was demanding at the time, partially to cover themselves in case there was difficulty. The sticker read : "WARNING : The inside fold out to this record cover is a work of art by H.R. Giger that some people may find shocking, repulsive or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way."

When a San Fernando Valley mother complained that her 13- year old daughter had purchased the record as a gift for her 11-year old brother (at a Wherehouse Records outlet in a large mall), the LA City Attorney's Office decided to prosecute the case. Deputy city attorney Michael Guarino, the prosecutor in the case, admitted they chose to prosecute the DKs because it would be a "cost-effective" way to send a message to other musicians, record companies and fans. Guarino had been considering prosecuting several other groups when this case came along, and he thought he could win this one.

The first Biafra heard of all this was when he was awakened from his sleep one morning by the sound of his window being broken and several police officers invading his house, supposedly to seize the "evidence." ( No one bothered to knock.) They took numerous personal effects, including his address book, as well as a few copies of Frankenchrist and the business ledgers of Alternative Tentacles, making it impossible to conduct business for a while.

Charged in the case were Biafra, and four others, including the 67-year old man whose company pressed the Frankenchrist disc. Conspicuously not charged were Wherehouse Records which sold the offending album. They had agreed to stop selling Frankenchrist and all other Dead Kennedys albums when the controversy first surfaced.

Biafra and the others decided to fight the charges of distributing harmful matter to minors, and set up the No More Censorship Defense Fund, which along with helping with the legal fees in the Frankenchrist case, makes available copies of articles dealing with censorship and plans to help others who are being harassed. Contributions came in mostly from fans of alternative music; envelopes of teenager's allowance and an encouraging note were common. Not so common were contributions from those popular figures who stood to suffer if Biafra lost the case. Three notable figures who did come to Biafra's aid were Frank Zappa, Little Steven Van Zandt and Paul Kantner.

Although Tipper Gore's PMRC did not claim credit for the case, they certainly approved of it, and it was their talk of rating records that led to the pro-censorship climate of the mid and late 1980's. ( Of course, they are very loath to call it censorship, even though several major record store chains had agreed to not to carry any record that contained a negative rating label.) The No More Censorship Defense Fund called for a boycott of Coors beer and other companies that financed the PMRC, and chronicled their activities in the newsletters inserted in DKs albums.

Finally, after months of delay, during which Biafra's time was taxed enough that he had no time to work on his music, the case went to trial. After a week-long trial in which witnesses such as Greil Marcus testified on the group's behalf, and a respected art teacher attempted to show how the poster was an integral part of the Frankenchrist package, the jury came out deadlocked (7-5 in favor of acquittal), and the judge dismissed the case.

Ironically, the painting which stirred up all the controversy had been printed in several books which could be found in libraries all across the U.S., all published without incident. Giger is a highly respected artist who had even won an academy award ( for his Alien set design), and found all the controversy very strange.

Alternative Tentacles News, May 16, 2001

The famous obscenity trial for the DK's Frankenchrist album resulted in a precedent setting victory for free speech, but nearly bankrupted the label. Amazingly, despite the numerous famous artists under attack at that time, only Frank Zappa and a couple of others tried to help.

RIP Magazine, June 1986

RIP: They're cracking down on rock 'n' roll in other ways too. Look at the lawsuit against Jello Biafra stemming from the poster inside of the Dead Kennedys' Frankenchrist album. Or the suit against Ozzy Osbourne because some father claims that it's Ozzy's fault that his kid committed suicide while one of Ozzy's records was playing. A spokesman from the L.A. District Attorney's office stated that he has a deskful of other possible rock 'n' roll prosecutions. Is this too going to become fashionable?

ZAPPA: It depends on the outcome of the Biafra case. Right now I'd take that folder on the other prosecutions and use it as evidence in the Biafra case to prove it's a conspiracy on the part of the judiciary and the law-enforcement officers in California, and that it's completely prejudicial and has nothing to do with anything in rock 'n' roll.

What I want to know is, how can a person in the San Fernando Valley who becomes irate at a rock 'n' roll poster in an album suddenly get a search warrant from the State Attorney General's office, requiring the service of six vice-squad officers plus three more flown up from Los Angeles, to search someone's house in San Francisco who's not presumed to be dangerous? That's nine guys, armed, going up to someone's house with a search warrant from the State Attorney General for the purpose of, as the warrant says, "To pick up three copies of the album." First of all, why not go to a record store and buy them? Then there's the slight matter of who's been indicted here, right down to the guy who pressed the albums. Notice it's not the Wherehouse record store that sold the records—a curious omission. And, they have to prove that by seeing this poster, someone has been irreparably damaged. It's an absurd case.

FZ, interviewed by Dave Turner and Lisa Weisberg, Buzz, March 1988

DT: Are you up on what Jello Biafra is doing on his anti censorship tour?

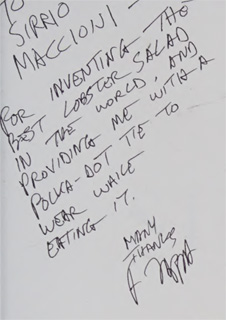

FZ: I know he's on tour, and he's made an album of some of it, but I haven't seen it. He's been over here (at the house) a few times. I've met him, but he's not a close' friend. I supported him during his trial. We put out something called a Z-Pack, and I provided him with all that data (on the PMRC, and censorship).

Richard Abowitz, "The Universe Of Frank Zappa," Gadfly, May 1999

When the punk label Alternative Tentacles was attacked by the government for the artwork included with a Dead Kennedys album, Zappa put his money alongside his mouth. Despite his antipathy for punk, Zappa made a sizeable donation to the No More Censorship Defense Fund and called up label owner and Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra. Biafra recalls being advised to remember that he was the victim and to keep his dignity. In all, they had about seven or eight conversations, and Biafra was invited over to Zappa's house.

Jeffrey Ressner, Rolling Stone, October 1987

The two-week trial of former Dead Kennedys vocalist Jello Biafra ended on August 27th in a victory for the singer when a Los Angeles jury was unable to reach a verdict. Biafra and Michael Bonanno, the former manager of Biafra's record label, Alternative Tentacles, were charged with distributing harmful matter to a minor. It was apparently the first court case to scrutinize the contents of a rock album. The jurors deliberated a little more than a day before declaring themselves stalemated, causing the judge to declare a mistrial and throw out the case. [...] But the singer added that the victory didn't come cheaply. Since his arrest, the Dead Kennedys have disbanded, and Biafra's marriage has ended. "I've been wearing Lenny Bruce's shoes for over a year, and I don't think they fit very well," he said, referring to the late comic, whose career tailspinned after several obscenity arrests. Biafra's legal fees total more than $55,000. Few members of the music community came to Biafra's support; Frank Zappa, Steve Van Zandt and Paul Kantner were the only high-profile rock artists to contribute to his defense fund.

Jello Biafra, "Punk Politics," alternativetentacles.com, 2004

Meeting Frank Zappa was one of the few silver linings to come out of the trial. He got a hold of me and the helpers of the No More Censorship Defense Fund rather than us having to find him. He gave me some very valuable advice very early on; something that anybody subjected to that kind of harassment should remember: You are the victim. You have to constantly frame yourself that way in the mass media so you don't get branded some kind of outlaw simply because of your beliefs and the way you express your art. The outlaws are the police. I got to visit Frank two or three more times at his house in Los Angeles and those were very special times. He showed me a hilarious Christian aerobics video. The women were in their skintight leotards doing jumping jacks. "One-two, two-two, three-two, praise the Lord!" And of course the bustiest one was in a striped spandex suit dead ront center of the screen!

- Jello Biafra is mentioned in The Real Frank Zappa Book (1989) p. 289.