1980—New Band

Warren Cuccurullo

Warren Cuccurullo, interviewed by Anne Carlini, "Destination Known: To Become A Solid Member Of Society, July 1, 2001

When we [The Missing Persons] had finished our little demo cassette, pre-studio, I get a call from Frank saying we're gonna be going on tour. So, I met up with him and brought this cassette and I played him the tape and told him I really wanted to do this and that I couldn't go on tour with him. It was such a hard thing for me to do, because I was the biggest Zappa fan, but these songs meant so much to me that I couldn't turn away from them. Frank helped us immensely. He let us use his studio to record and he'd never even recorded in it!

It was the hardest decision of my life. But there were always so many band changes and it got so I wanted a more permanent situation. I had been hanging out with Terry and Dale and we'd made about 10 songs together. We thought we had something special and Frank liked it. Then he called up to say he was gearing up for the road again and I said 'I think we're gonna do this band thing. He wished us all the luck in the world. So, with his blessings, we did it.

Warren Cuccurullo, interviewed for Planet Earth, February 1996

PE: Was there ever a point when you thought about ditching the Missing Persons idea?

WC: It was only at the very beginning when Frank called me and said "I am ready to go out on the road, I want you in the band." I said, "I'm going to come over tomorrow night, and I will talk about it." I went up there with a tape, and I explained to him what I had been doing, and he really liked it, and he couldn't believe that Dale could sing in time, because he was the one that discovered Dale, and put her on . . . you know she sang, the first words she'd ever sang was (sings) "Warren Cuccurullo" on "Catholic Girls." He just loved the sound of her voice. So, he couldn't' believe that she was singing, and he liked the stuff, but let me tell you, he said, it's not easy, and he took out a record, and it was a Devo album, and he said "you see these guys, they were the hottest thing last year, 2 years ago, and now nobody even wants to know about them," and um, it was true, you know how it is. It's very trendy and of the moment, and I have to say he was right, but he said if you want to do it, I wish you all the luck in the world, you've got my blessings, and if there is anything I can do to help just let me know. And I said, "yeah, Frank, I really do want to do it," and that was it. I made the decision at that point. I could have had another world tour under my belt, you know, to go out with Frank again, I would have learned a lot more, but I think I did the right thing. I don't regret not staying with him at that point, even though now that he is dead, I wish I had some more great times with him, but you know I had other great times with him even though I wasn't in the band.

Ed Mann

Q: What happened in 1980 and 1984?

E: 1980 I was drumming. Those bands, he didn't want percussion in them. No actually, 1980 I was doing another project.

Arthur Barrow

In mid-January of 1980 I got a call from Frank's wife, Gail. She told me that Frank was putting a band together and he wanted me to come down for an audition. I thought this was ludicrous. I said, "Frank has heard me play and knows what I can do, so I don't think I need to audition. Tell him if he wants to hire me, I will do it, but I am not interested in auditioning." He hired me.

Things were different as far as the pay on this tour, however. Instead of being on a year round retainer of $500 a week, we would be paid $500 a week for rehearsals (I got extra as Clonemeister) and then $1,000 a week on the road. This time, when we were not working, there was no pay.

Rehearsals began at Frank's warehouse in the San Fernando Valley on January 28th, 1980.

Ray White

Ray has been in the band twice. The first time, he felt a little bit out of place because he is an extremely religious person, and our band is not. And I think that there was some religious/emotional conflict the first time that he was in the band. He was always great: He has a good attitude about working and he did a good job. But I sensed that there was a certain amount of discomfort about him being there vs. the type of material we were playing. So I let him go. And later on I said, well, why not try him again, because I had a band that I thought his personality would fit in with. So I called him up, he came down and tried out, and it clicked right away. So he's been with me for the past two or three years.

He's got a really good blues style.

He's wonderful; he just loves that kind of music.

Ray White, "Ray White's Bio"

I toured with Frank until nineteen seventy seven . . . I left the band that year, but was called back into action in the midst of finishing the Walter Hawkins gospel album with Phillip Bailey, Maurice White, and the Tower of Power horns . . . I said YES!

New Drummer

Just after the ["I Don't Wanna Get Drafted"] recording session, about five weeks before the tour was scheduled to begin, I got word that Vinnie had decided to quit the band. He had been asked to record an album with some other group. It was his dream to do session work, and apparently he thought doing the record was more important to his career than doing another Zappa tour. [...]

The call went out to the L.A. musician world, and immediately there were 30 or 40 top players who wanted to try out for the gig. Frank figured a good way to audition drummers was to start by seeing if they could handle the basic, "Thirteen" rhythm.

Sinclair Lott

The story is this. As we all know Vinnie was in the band when he discovered that he could remain in town and make twice as much as touring with Zappa. I remember Arthur coming over one night after rehearsal and playing me some of the stuff with a new drummer Sinclair Lott, which seemed obvious to me at the time that this guy would never make it as FZ's drummer and I mentioned this to Arthur. Less than a week later David Logeman had been hired. That's all I know.

The auditions took place under some duress because Frank was pressed for time to find a new drummer and start rehearsing ASAP for an upcoming tour. I heard about the auditions and decided to go down.

It was essentially a "cattle call" that lasted four or five days that every drummer in Los Angeles showed up at, and many more flew to LA for. Everyone played the same kit. I heard a lot of guys that lasted less that 30 seconds. Frank would stop the band if he wasn't hearing what he wanted, thank the guy, and move on to the next drummer.

When I got up there he quickly told me the rhythmic subdivision of the tune, which as I recall was odd groupings of 2's and 3's. I don't remember exactly, but it wasn't in 4/4.

After we finished the first tune, he counted off another. When we finished that, he gave me a copy of the Black Page and asked me if I could sight read it. I said, "Sure, no problem," which was complete BS. I'd never heard it, and had no intentions of sounding like crap while hacking my way through a piece like that.

Anyway, he told me to hang around and later asked me if I could start rehearsals in a few days. We rehearsed all the material that came out on "You Are What You Is" and then Frank called and said he had someone else that would do the gig.

It was a bit of a blow but within three weeks I was touring Europe and recording with Freddie Hubbard's quintet.

David Aldridge

In January of 1980, I had the chance of a lifetime when Frank Zappa was holding open auditions for Vinnie Colaiuta's replacement. [...]

I'd met Vinnie when he played one night at the Baked Potato, where we struck up a conversation. [...] We stayed in touch, and one day, he let me know he was leaving the band and asked if I was interested in getting an audition. I was 20, had been playing odd meters for about five years, knew a little about polyrhythms from the Gary Chaffee books, but was not a killer reader by any means.

Still, the opportunity for the experience begged that I give it a leap. I spent probably two weeks listening to every Zappa album I could get my hands on, embarking on a crash course in extremely advanced drumming. I don't think I left the house during that time, because I did NOT want to miss the call to go audition.

It came on a grey and dreary afternoon. Los Angeles had been pummeled with rain, and the sun was nowhere to be found. I drove over to a North Hollywood rehearsal studio, took a deep breath, and went inside. I introduced myself to the guy at the desk, and a few minutes later, he ushered me into the actual studio . . .

The band was rehearing a version of "A Love Supreme," only it was "A Mouth Supreme" or something like that . . . funny as hell. A duplicate of Terry Bozzio's double bass kit was set-up, and in front it stood The Man himself.

Zappa welcomed me and described what he wanted to play. I asked if he minded if I jotted the directions down, and he had no objection. Arthur Barrow was playing bass, and he was also Zappa's musical director. When Zappa was away, Arthur led the band's rehearsals. I was in some pretty heavy company and was trying to remember to breathe . . .

The song was in 13/8, subdivided 4/4 + 3/8, (four measures) with a measure of 12/8 afterwards. I really wasn't sure what to play, but I knew I'd better listen to everything Arthur did, because he was holding down the fort.

We started, and it was absolutely surreal. [...] Arthur told me just keep time, and that's what I did. We played that 13/8 deal for a few minutes, then played some variations on the 12/8 measure with a 7/8 turn-around . . . I was able to make sense of it, but when it came to playing reggae in 13/8, I was toast. I couldn't conceptualize it, and while it was frustrating to not continue, I had no complaints.

Zappa shook my hand and thanked me for coming in. He looked you right in the eye, and there was a value in that moment I have cherished for years.

That day taught me that ANYTHING is possible, and I mean MILES beyond what you might think. Not too long ago, I sold a cymbal to the drummer who eventually got the job. We talked about the audition, and I learned that he'd attended Cal Arts, where he learned a great deal about advanced drumming, polyrhythms, etc.

Douglas Bowne

Douglas Bowne, interviewed by Sara Valenzuela, www.saravalenzuela.com

Entonces me llamó Iggy Pop porque unos amigos le contaron de mi y extrañamente la misma semana también me llamó Frank Zappa. Yo tenía que decidir con quien irme, dos semanas antes una amiga me había invitado a un concierto de Iggy Pop y me pareció un gran artista. [...] Entonces decidí que tenía que tocar con él porque era muy bueno. Entonces llamó Zappa para ir a hacer una audición a los Angeles pero en ese entonces no me pareció muy interesante tocar con él ese tipo de comedia musical, me pareció que parte de su material sonaba un poco tonto, en ese entonces yo odiaba la fusión, por supuesto Zappa fue un gran artista y mucho de su material es genial. Era un hombre fuera de serie. Al final me fui de gira un año y medio con Iggy.

Translation:

Then Iggy Pop called me because some friends told him about me and strangely the same week Frank Zappa also called me. I had to decide whom I was going with. Two weeks earlier one friend had invited me to an Iggy Pop concert and I thought he was a great artist. [...] I decided I had to play with him because he was so good. Then Zappa called to audition in Los Angeles, but at that time I wasn't so interested in playing with him that kind of musical comedy. I thought some of his material sounded a little silly, I hated fusion at that time. Of course Zappa was a great artist and most of his material is brilliant. He was one of a kind. Finally I went on tour with Iggy for a year and a half.

David Logeman

You auditioned for Frank Zappa, primarily a rock musician known for composing his songs, with charts and sheet music for each player. Did you ever listen to what a previous drummer of Frank's did with the material or did you rely on your ability to read the sheet music?

I didn't listen to previous performances because of the time factor. I was a fan of his, but by the time I played with him I'd stopped listening to him. I was reading some stuff, and wasn't that concerned with those that had previously performed it.

With written drum parts, do you ever stray from what is on the page?

My own personal philosophy is to play what is written. To me, you are dishonoring the composer (if you don't). You should always play it exactly as written first.

In your estimation, what was it that separated you from the 50 or so drummers that auditioned for Zappa for that spot?

Even though I was replacing Vinnie Coliauta, he didn't want a Vinne Coliauta-type player. The fact that I could play jazz and rock was a big deal.

How did you prepare for it?

I didn't prepare. Every time I went in it was a different scenario.

Was it as grueling an audition as it has been suggested?

Absolutely. When I first went, there was a drum set there, and they were playing in 13/8 and 11/8, but they didn't tell the drummer that. Frank would hand him the sticks and say, 'Play.' If the drummer could not find the 'one,' he would stop the band and tell the drummer to go home. I was smart enough to move to the back of the line. By the time it was my turn, I knew what they were doing.

How did playing with Zappa change your development as a drummer?

I don't know if it changed my development, but it validated it. I was always intent, from early on, to try and learn all styles, to play in authentic situations to learn those styles. I wanted to learn to read as well as possible. I wanted to be prepared for anything that would be thrown at me, and, of course, that was the ultimate. Frank Zappa is the ultimate at throwing things at a drummer.

Transcriptions

Steve Vai

I got a tape from a kid—I think he's eighteen—named Steve Vai. He plays Stratocaster, and he's going to Berklee [College of Music in Boston]. He sent me a cassette, and it was fantastic; I mean, this kid has got incredible chops. He said he wanted to play the "Black Page Number One" [Zappa In New York] on the guitar and asked me for the music. So I sent it to him, and he sent me a cassette of two versions of it—one at metronome 58, and another one at metronome 84; I mean, if you saw it on paper you'd realize what a problem it is to do that at 58. It's a slow metronome tempo, but it's still fast when you get to the fast parts. And he got it going so fast that you could just barely discern what the melody was. That's pretty much the faster is better. But he's got an awful lot of chops, and he sent me a cassette of some original compositions that are real nice. I think he's going to turn into something.

How did you first meet up with [Steve Vai]?

He sent me a cassette. When he was 17.

And he was in a music school at the time.

Berklee.

Steve Vai, interviewed by Michael Brenna, Society Pages #10, May 1982

I've always been an avid Frank fan, and I have all his records. Not fanatical, but for the music end of it, I really like that. Then I transcribed a song called "The Black Page," and sent it to Frank along with a tape of my playing. He liked it, and then I sent him the transcription of a song called "Black Napkins." He hired me as a transcriber, you know listening to the music and writing it down. I transcribed all the guitar solos on Joe's Garage, and a lot of the stuff on the Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar records, which is now being put in book form to be published.

Steve Vai got the job because he sent a cassette and a transcription of "The Black Page," and from hearing that, I could tell that he had a superior musical intelligence and very great guitar chops. And this showed me the possibility to write things that were even harder for that interment than what had already been used in the band. That's why he got the job.

When I heard "The Black Page" by Zappa, I almost died. I couldn't believe it. [...] I was just awed by it, and I tried to transcribe it. It took me months. I did a rough copy of it, and then every week I'd add something to it. That's when I was first exposed to artificial groupings—like when you take an odd number of notes, say, and put them over one or two beats. It's just out of your ordinary type of rhythmic structure. Here's an example of this kind of proportional grouping: Start with a normal grouping of a dotted eighth-note with a sixteenth. This is a normal grouping; you take the beat and it is divided into one or two or four—but it's even. Now, when you take something like five and put it over an even beat, it's called an artificial grouping, or a polyrhythm. That is, you have two rhythms going at once. And that's what I discovered about "The Black Page": There are a lot of polyrhythmic things in it. And I remember saying, "If you can do this, you can do that." One thing led to another and I transcribed "The Black Page" ["Zappa In New York"]. I sent it to Frank and he wrote back telling me that he liked it, and he offered me a job transcribing. I took it, of course: Frank was my favorite. [...] I was 18 or 19 when I transcribed all the stuff that's in the book. I started transcribing then, and I just finished, right before the 1982 tour.

[...] I was in my fourth semester—I went straight summers and all—and right at the very end of the fourth semester I got the call from Frank to start transcribing. I was living in a Boston apartment about the size of my kitchen, with mice that you had to wrestle with. It was incredible. Well, working for Frank is a full-time thing, you can't go to college and work for Zappa—it just doesn't work. So it was a choice, and of course I started working for Frank. Right away, I was transcribing anywhere between 13 and 15 hours a day. That's nerve-wracking. There's a huge stack of my transcriptions that I'm sure he'll eventually find use for. God, I really worked my ass off. At the beginning I was getting paid nothing—I was getting paid like $10.00 a page, which is what a lead sheet transcriber would get. And I used to cram this stuff on the page and cram all the staffs so that Frank would see that I wasn't trying to rip him off. [...] Well, $10.00 a page was still a lot of money for someone who was living on $10.00 a week! And I remember the first one I did that I was on salary for was "Outside Now" ["Joe's Garage, Acts II & III"]. Then I did "He Used To Cut The Grass" ["Joe's Garage, Acts II & III"]. And this stuff was transcribed using a cassette recorder that was so small and weak and lousy. It was really hard. I used to sit and listen to one bar of music maybe a hundred times—hours and hours and hours of music. But it was fun; I enjoyed it. I felt useful. I was learning. I think that transcribing is one of the biggest learning experiences for a musician, and it's really good for a person.

Steve Vai, interviewed by Adrian Belew, Guitar For The Practicing Musician, January 1994

I was going to Berkeley at the time and I was such a big fan of Frank's, I had transcribed "Black Page" and sent it to him. He was pretty blown away with it. So he sent me all these guitar solos and asked me to transcribe them. Which—if you know the way Frank plays—(is) not like a jazz player blowing over eighth notes, it's just attacking the strings with vengeance. Especially with Vinnie (Colaiuta, drummer) going off onto Venus. I actually did my best to transcribe the guitar and drum parts. It was a lot of fun because it was like an art project. It's not like a sax solo or an Allan Holdsworth or (Al) Di Meola solo. I had an opportunity to explore these twisted notational rhythms. I really got my ears together because I transcribed for four years and it came to the point where I didn't use a guitar anymore or any instrument. My relative pitch got really good. Frank started sending me all sorts of things from lead sheets to orchestra scores where he had orchestrated certain sections, like "Gregory Peccary." Other sections weren't orchestrated, they were just put together by Frank and he wanted to have the score for it.

[...] I transcribed the orchestration. I remember being amazed, sitting at airports with Frank and he would suddenly pull out some music and sit there and start writing. He did that all the time and I'd always try to get in on what he was doing and he would never let on.

[...] The thing I got most from Frank is he is a very honest guy. [...] There was one episode I remember from when I was transcribing. Fifteen years ago you had to have lead sheets for all your songs. And they paid you per bar. There was one song I was doing that could have been done in 2/4 or 4/4 and I went to Frank and said, "I can do this in 2/4 and there'll be more bars and you can get paid more." He said, "Just do the song the way it should be done—I don't need to make my money that way." That episode really stunned me. (He's) right—you don't ever need to make your money that way.

Steve was around 16 years old when one of his buddies showed him a Rolodex he had stolen from a New York recording studio. Steve could not believe it when he saw his idol Frank Zappas number right there in black and white. So he called Mr. Zappa, but his wife Gail answered. She was patient in listening to Steve profess his love for Franks music, and Gail mentioned to him that Frank is on tour but you can call back in 6 months. And teenage Vai did just that, every six months he would call the Zappas home. (Sometimes, Gail Zappa would answer, but Frank was never available).

Finally, in Steves first year at Berklee when he made his annual call, Zappa actually happened to be around, picked up the phone and was in a talkative mood. Steve had read that Frank was looking for some Edgard Varese scores, and Steve, wanting to impress Zappa, suggested he could xerox them from the Boston Library and send them to Frank. Feeling the timing was right, Steve suggested he could also send his transcribed version of Zappas 'Black Page' and the Morning Thunder demo tape. Frank said, 'Sure.'

Vai thought maybe that was all of the interaction he was going to have with Frank. But Zappa was thoroughly impressed with Steves transcription as well as his playing. So Frank suggested that Vai record himself playing 'Black Page' both at regular tempo and as fast as he possibly could. Steve did so and sent Zappa the recording. It was so good, that he wanted Steve to try out for his band, but once he found out how old Vai was, Zappa felt 18 was just too young for everything recording and touring would demand. But Zappa did hire Vai to transcribe his music at $10 a page.

Steve Vai, November 2022, on the liner notes of Zappa '80—Mudd Club/Munich (2023)

In or around 1978 when I was 18 years old, I had the opportunity to talk with Frank on the phone. He allowed me to send him some materials such as xerox copies of some Edgar Varèse scores, a transcription I did of "The Black Page" and a tape of my band from Berklee College of Music. After he heard my tape, he wanted to try me out for the band but when I told him I was 18 he said, "Forget it, you're too young." But he did hire me to transcribe a truck load of his recently recorded guitar solos and Vinnie Colaiuta drum tracks at that time.

Billy James

I first met Frank in 1977 after a gig at Atlanta. It was as brief as could be. I shook his hand and said hello, and that was about it. It wasn't really until about 1980 that Zappa was looking for a copy of this ten record boot that someone had released, and I had quite an extravagant collection of recordings. Steve [Vai] would borrow some of my tapes and he told Frank that I could probably get him the record. I did track it down for him. I went backstage at Rhode Island and 1980 and gave him the set, and also handed him some of my chart work. Steve was doing a lot of the transcriptions of the jams from the live shows, the spontaneous improvisations. Steve is probably the most amazing transcriber in the world. There are rhythms in this stuff that I cannot believe he could transcribe because they are so difficult and foreign to ninety-nine per cent of the musicians in the world. So he was feeding me some of these transcriptions. A lot of these polyrhythmic figures were so difficult that I developed a mathematical formula that demonstrated how these figures worked.

So I'd handed some of these charts to Frank, never expecting to hear from him. Then a few months later, I got a letter from him telling me how much he appreciated the charts. This lead to me doing some more charts for him which I guess he used to teach the band members how to play certain rhythms. He will often use some of the rhythmic figures to write things. A lot of the band members, even though they are excellent players and readers, could not understand how these rhythms worked. I remember doing some things like 'Stucco Homes' and 'Joe's Garage' and a few live things. So it wasn't really an awful lot.

March-May 1980—Spring Tour, US

April 5, 1980—Swing Auditorium, San Bernardino, CA

Mark Lundahl, "Zappa Sings Medley Of The Unknown," The Sun, Baltimore, April 7, 1980

SAN BERNARDINO—"Hello. We haven't played here for 11 or 12 years, and they still have that ugly stuff hanging from the ceiling . . . Well, that's progress."

Yep, snide old Frank Zappa was back at Swing Auditorium with a new show, a new look, and his first tour in 2 1/2 years.

The hair was no longer a tangled mop. A recent haircut took care of that. But the droopy mustache, droll humor, and instrumental finesse remained.

It's wise to expect the unexpected at a Zappa concert, and Saturday night that meant no oldies: No "Dynamo Hum," no "Peaches en Regalia," and (gasp) no "San Ber'dino."

Instead, nearly all of Zappa's two-hour-plus show was devoted to new, unreleased material. A few selections from Joe's Garage, the instrumental "Black Napkins," disco (?) his "Dancin' Fool" as well as a cover of Tony Allen's "Night Owl" were added for good measure, but for the rest of the evening it was a medley of the unknown.

Instrumentals did not play a major part at this concert. The new material was vocal-intensive with black singers Ike Wills and Ray White taking most of the parts.

As always, off-beat subjects and blue humor was the order of business. Some of the topics covered: Coneheads, Dumbo, suicide and TV preachers. Some of the songs: "Charlie's Enormous Mouth," "Beauty Knows No Pain," "Heavenly Bank Account" and "Harder Than Your Husband."

It might have helped if the security guards outside had handed out lyric sheets as they were frisking the audience. The close harmonies and fuzzy acoustics often buried the humor.

Instrumentally, the band did not quite play with the precision of some of Zappa's past groups. Only keyboardist Tommy Mars was really impressive, particularly with his synthesizer colorings.

And Zappa, whose guitar once seemed to be a permanent appendage to his body, only picked up his axe on occasion (the concert's fines moments), choosing to spend the rest of the time darting around the stage, mike in hand, like some demented cabaret crooner.

Well, that's progress.

April 11, 1980—Henry Levitt Arena, Wichita, KS

I contacted Frank when he came to Wichita for his concert. Earlier that week I had been recognised by the board of the Wichita Jazz Festival as the New Aspiring Artist in Wichita. When I asked them if I could play, they said that I had not submitted a tape according to their process. I asked them why the Joe's Garage album I had recently recorded on wasn't sufficient and that I would think that a local player who had just recorded with Zappa would be joyfully showcased, but they blew me off. I shared this with Frank, so when he introduced me to my home town audience, he stated this: "The Wichita Jazz Festival won't let Twister play, I think that stinks so we are going to feature him here with us tonight!" Typical Frank Zappa, a phenomenal artist who would go to bat for a tree trimmer who was on the correct side of an ethic!

April 29, 1980—Tower Theater, Upper Darby, PA

May 8, 1980—Mudd Club, NYC, NY

US & Canada Tour—October-December 1980

Rehearsals

When I got to the rehearsal studio on September 15th, 1980, I was surprised to see that David Logeman's drums were not set up. A completely different set was in place. That was the first time I heard that Vinnie was back in the band. There were other changes, too, with the addition of Bob Harris on vocals, keys, and trumpet, and a 19-year-old Steve Vai on guitar. [...] I was the Clonemeister again, but this time, the biggest problem I had was getting the band back on their instruments to resume rehearsal after breaks.

Steve Vai

I transcribed a song called "The Deathless Horsie" ["Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar Some More"], and Frank asked me to learn it on the guitar. He knew I played guitar because I'd sent him a tape he'd said he liked. So I told him I'd try. I learned the song, and I guess it was pretty good because he used it on the record and went into the studio and doubled the original guitar part. And if you listen to the album, you can hear two guitars—I'm playing exactly the same part as Frank; I doubled the solo. You can hear the distinction, though. So when that happened, Frank had written a piece which turned into "The Second Movement Of The Sinister Footwear". It sort of looks like the other transcriptions looked—really weird. I learned that, and I think he was impressed with it. So, he asked me if I'd do some overdubs for "You Are What You Is". So I ended up redoing about 80% of the guitars on the album. He had me down to rehearsal, and I got the gig.

Steve Vai, 2nd Annual Surround Music Awards, December 11, 2003

Here I am, 20 years old and Frank tells me to learn something like 40 songs to try out with the band at rehearsals. I get there and obviously he doesn't choose to perform any of the songs that he told me to learn. He picks up the guitar and awkwardly and slowly plays a very unorthodox fingered melody line. "Play this," he says to me. So I'm like, okay, and I play it. He says, "Faster." I said, "Okay" and played it faster. He goes, "Okay, now play it in 7/8." I think for a second and say, "OK," and I play it in 7/8. He says, "Now add this note." Okay, I add the note and play it in 7. And he goes, "Now reggae, 7/8 reggae." This is a true story. I thought for a minute and said, "Okay, I got it." and I played it in 7/8 reggae. He goes, "Okay, now add this note." And he played a note on his guitar. I thought for a minute and then I looked up and said, "Um . . . that's impossible," because it was impossible to do on the guitar. It was just physically impossible for anyone to do on the instrument. And Frank says, "Well, I hear Linda Rondstadt is looking for a guitar player."

Steve Vai on Guitar Magazine, February 1994

When I had gotten on the road with Frank, I was a nervous wreck. I wasn't eating right, I was sick, I was fooling around all the time. I was 19 years old and I was out there and I got no respect from anybody on the crew. I was under a lot of pressure because the music was so hard to play and I didn't want to make any mistakes. I did—it was inevitable—but the music was extremely hard and I had to keep practicing all the time. But, it was all really just nerves. I thought Frank was going to send me home. Why he didn't, I don't know.

As far as playing guitar, some people are born with inner time and some people just have to work on it. I didn't even realize what it was until I started working with Frank. He just sat and tried to punch me through this one [song] and I said, "I don't understand, Frank." I'm surprised he didn't fire me or just say, "Forget it, I'll get somebody else." But he was patient with me and explained to me what it really meant to be in time.

Vinnie Colaiuta

RF: You played double bass with Zappa?

VC: Here's what happened. When I started with Frank, for the first two tours, I had this little Gretsch set with one 20" bass drum and he loved it. But after a while, I wanted to go out and get a bigger bass drum, a 22" or something. He said, "No, I'll make it sound good." So he went out and got a lot of outboard gear and made it sound good. He just loved the idea of this little set I was playing. I sat like two inches off the ground and he kind of liked the concept of where I was coming from. I guess he wanted to get into a different approach, drumwise. Finally, on the last tour I told him I wanted to play two bass drums. He said, "No, because we'd have to leave one mic open all the time and there would be problems acoustically." But finally I convinced him and just took them on the gig. I didn't really practice on them, but when you rehearse a tour with Frank, you rehearse for like two months, eight hours a day, before you go out. So I got a chance to get used to them in rehearsals. But it took a while. We went on the road for three months or something, and by the middle of the tour, they started feeling good.

[...] It's funny, because my whole equipment scene evolved to a point with Frank where at the end of the time I was with him, I had two bass drums, I had a Synare electronic bass drum in the middle of those two drums, a real snare, a Synare snare, timbales, four Syndrums, five Synare tympani, tom-toms, Roto-toms, the two cymbals on top of one another, and one of those splash cymbals that is cut out of a hi-hat so it sounded real thick. I was starting to think of it more like all these sound varieties to the point where I'd come up with grooves that you wouldn't normally do on a hi-hat and one bass drum. Nowadays, I'm playing one bass drum, two tom-toms, two floor toms, a ride cymbal, two crash cymbals and a hi-hat.

Craig Steward

FZ quoted on Rock et Folk, June 1980 (translation by A. Murkin)

He came for an audition at the time of Roxy and Elsewhere. He was already very good, but he couldn't learn his parts fast enough, not as fast as George Duke and the others, he was slowing us down. I said to him: go home and work, and call me when you're ready. That's what he did, and now he's in the group.

Recordings

Frank Zappa Sessions Information, compiled by Greg Russo, August 2003

12/03/80 (2 shows: 7:00PM and 9:30PM) The Terrace Ballroom, Salt Lake City, UT—no titles listed

MUSICIANS: FZ (leader), Isaac Willis, Steve Vai, Ray White, Vincent Colaiuta, Thomas Mariano, Robert Harris, Arthur William Barrow

12/05/80 (2 shows: 7:00PM and 10:30PM) Berkeley Community Theater, Berkeley, CA—no titles listed

MUSICIANS: FZ (leader), Isaac Willis, Steve Vai, Ray White, Vincent Colaiuta, Thomas Mariano, Robert Harris, Arthur William Barrow

12/08/80 (7:30PM performance) The Arlington Theatre, Santa Barbara, CA—no titles listed

MUSICIANS: FZ (leader), Isaac Willis, Steve Vai, Ray White, Vincent Colaiuta, Thomas Mariano, Robert Harris, Arthur William Barrow

12/09/80 (performance time not listed) San Diego Civic Auditorium, San Diego, CA—no titles listed

MUSICIANS: FZ (leader), Isaac Willis, Steve Vai, Ray White, Vincent Colaiuta, Thomas Mariano, Robert Harris, Arthur William Barrow

12/11/80 (2 shows: 7:30PM and 10:30PM) Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, Santa Monica, CA—no titles listed

MUSICIANS: FZ (leader), Isaac Willis, Steve Vai, Ray White, Vincent Colaiuta, Thomas Mariano, Robert Harris, Arthur William Barrow

Mark Pinske, January 26, 2003

We used a 24 track when we got back to the states and most of the recordings we did overseas were on a SoundCraft 1 inch 8 track.

[...] Klaus was helping early in 1980, but George [Douglas] did the rest of that and we had cased up the 24 track machine, because Frank was not real happy with the 8 tracks form Europe, etc., and we were trying to improve the live recordings all of the time. Some of them came out OK. It wasn't until we built the recording truck and I stopped mixing the house that we got the real good stuff because the truck allowed us to have more control over everything.

George Douglas, who joined the organization in 1980, remembers making road tapes from a position just behind the stage with two Yamaha PM1000 consoles and a Tascam 8-track. "It was obviously less than ideal, as far as monitoring went," he notes. "After the European tour, I asked for and got a Midas 32-channel 8x8 and set up a Dolby rig and two 3M M79 24-tracks."

October 12, 1980—Albuquerque, NM

I remember one time, I think it was eighty-one, nineteen eighty-one, I had just done the album "You Are What You Is" with him, and he played in Albuquerque. I was living in Albuqureque, New Mexico at that time. And he played a gig there, it was one of the first gigs of the tour. And he asked me to sit in and sing "Harder Than Your Husband" with the band. And I did. And he said "come on backstage", before I went on. "Have a glass of wine with me". And I said, you know, at that time I wasn't drinking anymore. I had quit, I think for five or six years I didn't drink anything, no alcohol. And that was at that time. "I'm sorry, Frank, but I'm on the wagon." "OK... All right." He was cool. Most of the time, he was cool.

October 12th 1980 was [my girlfriend] Husta's 40th Birthday and that is when Frank and the band came to Albuquerque on their tour. It was the second gig of the Crush All Boxes tour.

We went to the concert and Husta was backstage with me when Frank invited me up to sing "Harder Than Your Husband" with them. The show was actually recorded and broadcast by the local television. [...] Before the show, Frank and I went to the local college radio station and did an interview with them. Frank explained why the new LP was going to be called Crush All Boxes instead of Fred Zeppelin, which is what he was originally going to call it. John Bonham had just died so he changed the name out of respect. Probably the only time Frank would do something like that.

At the time, I was on the wagon and wasn't drinking anything alcoholic at all. Frank offered to have a drink with me but I had to explain to him that I couldn't accept because it wouldn't work for me.

After the show, we were having a party for Husta at one of our friend's house and so we invited everybody back to the house. The band all came back but before anyone came in, John Smothers, who was Zappa's bodyguard, went in and said, "All Pot will be put out before Frank comes in!" Boy, that really pissed Dee off, the chick whose house it was, and she said, "I don't give a fuck whether he comes in the house or not, Man! This is my fuckin' house and if I wanna smoke Pot in it, I'm gonna!" So anyway, Frank came in and he stayed for about 30 or 40 minutes with his cup of coffee while the rest of us kept on smoking our Pot. Vinnie Colaiuta, Arthur Barrow, Ray [White] and Ike all came in the limo with him and, when he left, they stayed and smoked their fucking brains out with us.

October 18, 1980—Tulsa, OK

Hog Heaven

Recording Date 10/18/80

Recording Location Brady Theater, Tulsa

Engineer George Douglas

Facility UMRK remote

October 25, 1980—Buffalo, NY

October 30-November 1, 1980—The Palladium, NYC

When I was here the last time at Halloween, I had the flu so bad, I couldn't even stand up and for 4 out of the 5 shows, I managed to get through it. I had to cancel the fifth one cause I was so weak I thought I was gonna have to go into the hospital and that was the beginning of the tour. I thought I was gonna have to cancel a bunch of dates and I had to knock off the last show.

"To Henry [Goldrich] from F. Zappa and the guys"

[Ray White, Bob Harris #2, Ike Willis, FZ, Tommy Mars, Steve Vai, Vinnie Colaiuta, Arthur Barrow]

"Another Variation Of The Formerly Secret" [...] (Recorded live at The Palladium, NYC, 30 October 1980)

[...] Mixed with Bob Stone at UMRK, ca. 1981

Original Recording Engineer: George Douglas

Allen Sides?

Allen [Sides] did some of the live tapes at the New York Palladium. Before we had the truck, we rented the Record Plant truck. And Allen had done that.

At the Roxy in New York, and at one of the other shows in New York, we did rent a truck. We had the Record Plant truck one year. I'm trying to remember what other truck we used. We used the Record Plant mobile one year, that Allen Sides helped out with. And there was a couple of times in there where we had the truck.

Román

Could Pinske actually be referring to the Tower Theater, Upper Darby, PA, April 29, 1980 recordings?

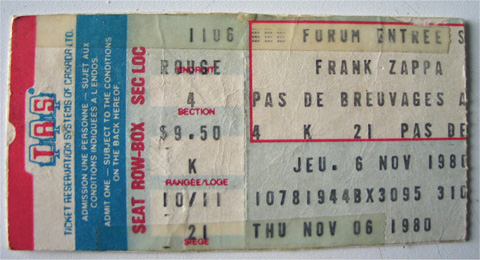

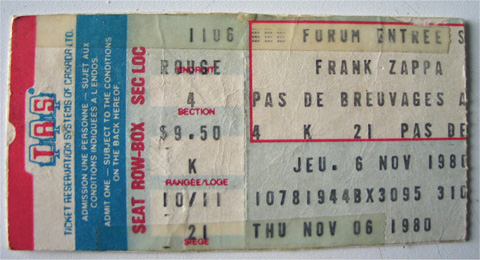

November 6, 1980—Forum, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

November 15, 1980—Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL

Alan Sculley, "Audience Reaction Is Major Catalyst At Zappa Concert," The Daily Egyptian, October 17, 1980, p. 8, 11

About 7,000 Arena fans were welcomed Saturday night into the strange and unique world fondly known as Frank Zappa's mind.

In the dark recesses of his universe come thoughts that no normal man could think of. His is the work of a strangely creative man; one who, throughout his career which spans approximately 15 years, has showcased his ability to change and adapt to whatever the situation seems to require.

This ability was in clear evidence Saturday. Zappa was very nonchalant about everything going on around him, reeling off snappy remarks and short bits of philosophy throughout the show. In short, he was in typical form.

After a disorganized instrumental which opened his set, Zappa strolled up to the microphone and announced a unique offer to the crowd—the raffling off of drummer Vinnie Colaiuta.

The deal was simple. Zappa instructed any female wanting Colaiuta for the night to throw her underpants on the stage and the drummer would chose the winner as the pair that pleased him most. It was an icebreaker in the vintage Zappa style. And he milked the "contest" for all it was worth, keeping the joke alive during the entire two-hour show.

Zappa's ability to play off of audience reaction was a major catalyst in the success of this performance. Some examples are:

—One raffle contestant threw her slip on stage, so Zappa immediately put it on his head, creating a walking, talking Sheik Yerbuti.

—Another audience member threw a miniature shark with the word "mud" printed on its side, prompting Zappa and the band to launch into an impromptu version of "Mud Shark," off his 1971 live album from the Fillmore East.

—Another audience member handed Zappa a giant-size graduate student identification card with his photo on it. This quickly became a backdrop for the riser in front of the drum set.

Spontaneous stage ploys such as these combined perfectly with Zappa's suave stage manner. Whether he was sitting on a stool in front of the drums, grabbing a quick smoke while his band played on, or taking a miniature pointer and conducting his band a la Lawrence Welk, Zappa was simply entertaining.

In fact, Zappa's stage demeanor so dominated his songs that the music often took a back seat to his off-the-cuff wisecracks.

Zappa's unstructured and often unimpressive music is his main weakness. His wandering songs serve only as a framework for his lyrics. This weakness was very obvious throughout the Arena show, when the band performed a tedious half-hour jam that just seemed like [noise] being created on stage.

If it weren't for an occasional panty being thrown on the stage, which spawned some hilarious comments by Zappa and the band, this section of the show would have suffocated an extremely tight sequence of songs.

It was not until the mud shark hit the stage near the end of the show that the band recovered its early pace. Zappa used the tune to weave a yarn about a motel in Seattle, Wash., which is built on a peninsula, where guests fish out the windows of their rooms.

He then closed the show with an encore set which pushed the crowd back to the loud cheering clamor which greeted Zappa when he took the stage.

This brings up an interesting point. Zappa played a surprising sequence of songs, omitting such well-known tunes as "Dancing Fool" and "I Want A Steamy Little Jewish Princess." Only the classic "watch out where the huskies go and don't you eat that yellow snow," and "Joe's Garage," which was his first of two encores, remained in the show.

But in the context of the show, this arrangement of songs was not so surprising, as he was always doing the unexpected. This is part of what makes Zappa an attractive performer. While some bands stick to a tightly planned sequence of music, Zappa is likely to do whatever seems natural when the mood strikes him.

Fortunately the mood was good Saturday night, and so was Zappa.

Informant: Javier Marcote.

November 16, 1980—Madison, Wisconsin

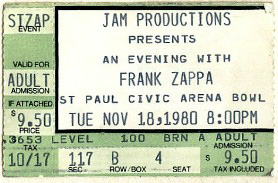

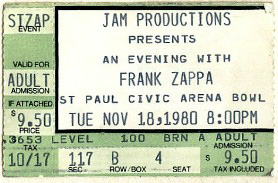

November 18, 1980—Civic Arena Bowl, St. Paul, MN

Yesterday Wafflez

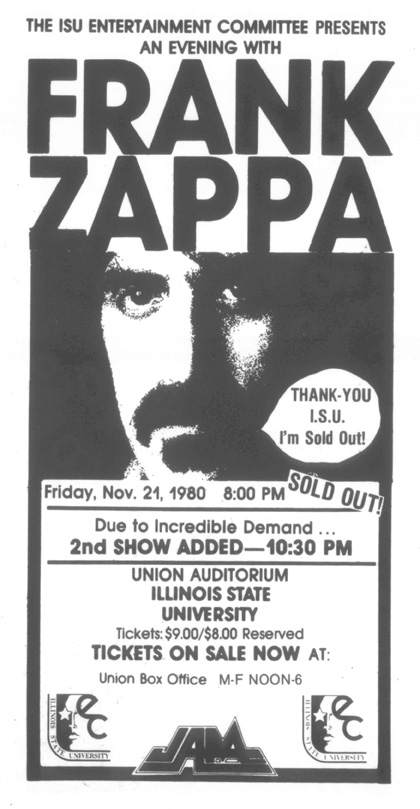

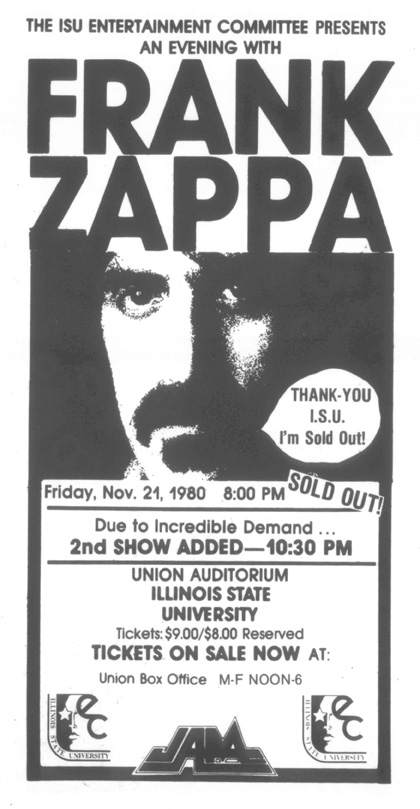

November 21, 1980—University Union Auditorium, Normal, IL

Daily Vidette, October 29, 1980, p. 6

Extra Zappa show set

The Entertainment Committee announced Tuesday that Frank Zappa has agreed to a second concert performance at 10:30 p.m. on Nov. 21.

Tickets for the performance go on sale from noon to 6 p.m. today at the Union box office, and will conctinue until sold out. the concert is a Jam Production.

Tom Naughton, "Zappa Performance Filled With Goods, Bads," Daily Vidette, November 23, 1980, p. 7

It looked like it could be a crazy time, the kind of experience people who would go to see Frank Zappa would expect.

Zappa came out on stage to start the first show at the Union Auditorium Friday and asked for any girls in the audience who were willing to throw their bras and underwear up to him because, he said, he wanted to make a quilt out of them.

He even had a clothesline on the stage with garments gathered at previous concerts hanging on it. The audience began to warm up in anticipation of more craziness.

By the time the concert was over, however, the mood established at the beginning had been dragged down by too many long jams and not enough rapport-building by Zappa himself.

Not to say the music wasn't good. It was, in fact, superb. Zappa and his seven-member band showed they can play virtually every kind of music. The songs ranged in sound from blues, to heavy metal, to big-band. There was even a satire of Bob Dylan. Many of the songs featured excellent three-part harmony.

But every time the band began to generate some momentum on stage, they drowned it in long instrumentals that only hard-core Zappa fans could really enjoy.

Zappa is an excellent guitarist, but his long leads were probably not what the audience came to hear. When many numbers went by without any of Zappa's infamous strange lyrics being heard, the fact that the audience was not getting what it wanted showed in its response, which lessened in enthusiasm as the show went along.

Zappa's stage presence also left a lot to be desired. He spoke to the audience very few times compared with most performers; he simply played his music and usually went from one song right into another.

As with almost any concert, it took an encore to get the band to play its popular songs.

Zappa came back out on stage after leaving once and played two more songs, including "Yellow Snow," then left the stage again. Indeed, there was no clamoring for another encore.

Informant: Javier Marcote.

December 3, 1980—Salt Lake City, Utah

December 5, 1980—Berkeley

December 8, 1980—Arlington Theater, Santa Barbara, CA

Arthur Barrow, Of Course I Said Yes!, 2016, p. 113-114

One of the worst nights of the tour was a horrible night for anyone in the world who loved The Beatles. On December 8th, 1980 we played in santa Barbara at the Arlington Theater. I had just stepped up onto the stage and we were about to start the opening vamp when one of the roadies ran up to me and said, "John Lennon has just been shot to death in New York City!" I was in shock, then seconds later I heard Vinnie count off "One, two, three, four" and the show began. I played that whole show with tears in my eyes and my heart in my throat. Frank knew, also, I think, but wisely did not announce it to the audience. Because this was before the age of cell phones, they didn't find out till after the show. For the last few shows of the tour, we actually had some security checks at the doors of the venues.

There's two things I saw that meant a lot to Frank. The Hendrix guitar that was given to him, and then, unfortunately, the sad death of John Lennon. Which had a profound effect on him. [...] He almost didn't go on stage that night. We almost cancelled the show, I think. One of those things on the road, you know?

December 9, 1980—Civic Theater, San Diego, CA

Third time: 20 years ago today (well, tomorrow as I type this on the west coast), the day after John Lennon was murdered. I didn't see how anyone could play a rock concert that day and not acknowledge the horrible events of the night before, especially someone who had once shared a stage with the man. The least interesting of the Zappa shows I saw . . . lots of material that would show up on Tinsel Town Rebellion and YAWYI, plus all the cheap-shock stuff like "Bobby Brown," "Enema Bandit," "Broken Hearts Are For Assholes," "Honey Don't You . . ." and "Ms. Pinky." "Black Napkins" and "Torture" were nice. This was one of the panty shows . . . strings of undies all over the stage.

December 11, 1980—Santa Monica, CA