January 1983—Jam Session with Tommy Tedesco & Joe Pass

Joe and Tommy Tedesco were doing a NAMM show in Anaheim California in the early 1980s. [...] The story goes like this according to Joe Pass and I'm paraphrasing: "Tommy and I were both very excited to hear the Frank Zappa would be gracing our small stage that day at the NAMM show." Joe went on to say "In fact I was nervous, my palms were sweating, I had read and heard that this man was one of the greatest guitarists and composers of all time, like a modern day Mozart."

"We played a set, we waited, no Zappa, we played another set, still no Zappa. By this time, the suspense was killing both Tedesco and myself," (myself meaning Joe Pass.)

"At last, we see a dark haired man wearing a black long cape surrounded by a flock of worshipers coming toward our stage. We had to stop playing because there was complete chaos around our booth as Zappa was signing autographs and his fans were trying to touch his garment."

"After an hour of worship and autographs, he picks up a guitar and bangs out a couple of loud bar chords. Zappa turns to Tommy and asks, 'What do you guys what to play?'" Joe Pass started to rattle off tunes like Giant Steps, a John Coltrane classic, hey, Joe said, "we figured this Zappa guy is the best, lets play the most demanding music possible."

"After requesting more then two dozen standards, we realized this guy couldn't play any standards, not one. We ended up playing a TOO loud 12 bar blues, that's all Frank could play. It was pathetic."

Translation:

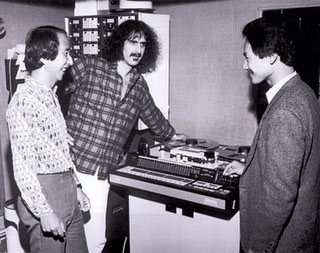

The photograph was taken in January, 1983, in the Pasta Michi restaurant in Sylmar, California, a real magnet for jazz guitarists, attracted by its owner, Charlie Chiarenza—Burt Bacharach's guitarist—, and where Pino played more than once in the mid 80s.

Pino says the reunion took place apparently due to a recording session that Tommy Tedesco did that afternoon for Frank Zappa, whom later he invited to the summit with dinner and 'zapada' at the restaurant. Between the present ones they are, from left to right, Tommy Tedesco, Jack Ranelli, unknown, Charlie Chiarenza, John Pisano, Frank Zappa and Joe Pass, not to talk about the vibe in the picture!

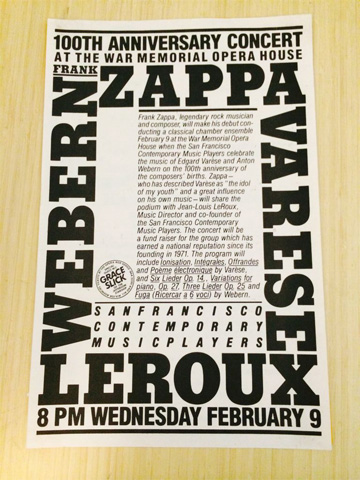

February 9, 1983—Varèse And Webern: One Hundreth Anniversary Celebration

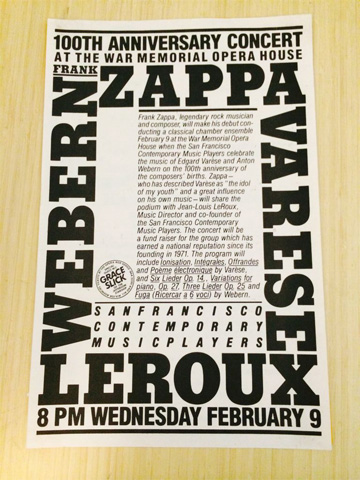

Poster

Frank Zappa, legendary rock musician and composer, will make his debut conducting a classical chamber ensemble February 9 at the War Memorial Opera House when the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players celebrate the music of Edgard Varèse and Anton Webern on the 100th anniversary of the composers' births. Zappa—who has described Varèse as "the idol of my youth" and a great influence on his own music—will share the podium with Jean-Louis LeRoux, Music Director and co-founder of the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players. The concert will be a fund raiser for the group which has earned a national reputation since its founding in 1971. The program will include Ionisation, Intégrales, Offrandes and Poème électronique by Varèse, and Six Lieder Op. 14, Variations for piano, Op. 27, Three Lieder Op. 25 and Fuga (Ricercar a 6 voci) by Webern.

Varèse And Webern: One Hundreth Anniversary Celebration (program)

VARESE AND WEBERN: ONE HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION

THE SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS

JEAN-LOUIS LEROUX, MUSIC DIRECTOR

MARCELLA DE CRAY, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

GUEST CONDUCTOR: FRANK ZAPPA

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 1983 8:00 P.M.

WAR MEMORIAL OPERA HOUSE

WITH INTRODUCTION BY GRACE SLICK

PROGRAM

INTRODUCTION

Grace Slick, Mistress of Ceremonies

IONISATION (1931)

for percussion ensemble of 13 players

Edgard Varèse

SIX LIEDER, Opus 14 (1917-21)

for soprano, clarinet, bass-clarinet, violin and cello

Anton Webern

VARIATIONS FOR PIANO, Opus 27 (1936)

Anton Webern

OFFRANDES (1921-22)

for soprano, piccolo, flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, harp, two violins, viola, cello, contra-bass and six percussionists

Edgard Varèse

INTERMISSION

POEME ELECTRONIQUE (1957-58)

for magnetic tape

Edgard Varèse

THREE LIEDER, Opus 25 (1934)

for soprano and piano

Anton Webern

FUGA (RICERCATA) a sei voci, No. 2 (1934-35)

from the "Musical Offering" by J.S. Bach for flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bass-clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, timpani, harp and string quintet

Anton Webern

INTEGRALES (1924-25)

for two piccolos, oboe, Eb clarinet, Bb clarinet, horn, trumpet in D, trumpet in C, tenor-trombone, bass-trombone, contrabass-trombone and four percussionists

Edgard Varèse

No photographic or recording equipment permitted.

All proceeds benefit the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players.

PLAYERS: Judith Cline, soprano; Marvin Tartak, piano; Roy Malan, Dan Smiley, violins; Ruth Freeman, viola; Bonnie Hampton, cello; Steven d'Amico, bass; Janet Lawrence, Barbara Chaffe, flutes; Deborah Henry, oboe; Marilyn Coyne, English horn; Jim Dukey, Tom Rose, clarinets; David Bartolotta, bassoon; Larry Ragent, French horn; Charles Metzger, Ralph Wagner, trumpets; Hall Geff, McDowell Kenley, John E. Williams, trombones; Marcella DeCray, harp; Danny Montoro, timpani; David Rosenthal, Todd Marley, Richard Kvistad, William Winant, Raymond Froelich, Perry Dreiman, Tyler Mack, Pat Scott, Ray Bachand, Kevin Neuhoff, Marvin Tartak, Jean-Louis LeRoux, percussion.

Frank Zappa, Jean-Louis LeRoux, conductors.

Crawford: In 1983 there was a benefit concert of Varèse and Webern with Frank Zappa. Talk about that. How was that put together?

LeRoux: I had heard that Zappa had conducted some pieces in New York. He had a tremendous admiration for Varèse, so I think I called him on the phone and said, "I would like to organize a concert. That would be the 100th anniversary of Varèse and Webern, and how about sharing the conducting—you conduct the Varèse pieces and I take care of Webern?" He said yes almost immediately. And he said, "My only problem is that I need a little bit of instruction, how to conduct, to handle these pieces." I said fine.

So I went to Los Angeles. I spent an entire day with him in his house, talking about music, and we talked about what to do and what to watch out for, and I told him it would be so well received and the Players would be so happy to see him and to be working with him, and he would not have any problems.

And he came with only one request, to be in a hotel where they have twenty-four-hour service, so he could eat anything at any time. [laughter]

Crawford: And you rented and nearly filled the opera house!

LeRoux: We had more than 2,000 people. I still have a hole in my stomach about the risk we were taking. [laughter] No, I don't know how much it cost. It's a lot of money to rent the opera house, a lot of money.

Crawford: You don't remember how much?

LeRoux: No. There were stagehands and everything that goes with it. It was a lot of money.

Crawford: But the board agreed. It was a great accomplishment.

LeRoux: We did it, and we made quite a bit of money, too. Several thousand.

Crawford: Grace Slick was the mistress of ceremonies. How did that happen?

LeRoux: I think that was Frank's idea to ask her, said she would do it, and she did, and she did a wonderful job.

STRANGE GOINGS-ON in the Opera House Wednesday. Some 2500 folk, mostly under 30s, vividly gotten up and down for the occasion, were there sitting in quiet awe of four delicately colored works by Anton Webern and wowed by Edgard Varèse's modernist "music noises," sensuous and otherwise.

Loud whoops went up periodically, a surprising one after the first of Webern's "Six Lieder," Op. 14, but mostly to greet the appearance onstage of rock heroes Frank Zappa and Grace Slick. It was the Varèse-Webern dual centennial celebration mounted by Jean-Louis LeRoux' San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, a benefit.

Zappa was there to conduct the Varèse "songs" as emcee Slick routinely called them: "Ionization" (1931) to open, and "Intégrales" (1925) to close the program. [...] He took his untypically formal role seriously. He shushed the greeting, responded to some shouts with "Let's get serious," turned, gave the beat in an audible "One, two, three, four" and awkwardly stroked out the conducting patterns, mouthing the count.

HIS STRICT marking of time and meter changes was enough for the SFCM Players to give Varèse a good, rhythmically clean, dynamically balanced go. "Ionization," with 13 percussionists on 34 instruments, was effective but no longer shocking, having made its influential point years ago. "Intégrales" for 11 winds, four percussion, was the hit, evocative of some primitive ritual, of contrabass shofars, battle horns, deep-lying forces.

[...] The SFCM Players were rewarded for the unconventional event itself, and properly. Popularizing Webern on a grand scale and with rock stars for bait? Well, no harm done.

Dan Forte, "An Interview With Frank Zappa," Mix, June 1983

In February, Zappa shared the baton with maestro Jean-Louis LeRoux for a 100th anniversary celebration of the music of Varese and Anton Webern, performed by the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players at the city's War Memorial Opera House. Though the concert was a bona fide success, Zappa admitted afterward, "It was the first time I've conducted anything by anybody else, and we only had two rehearsals. I didn't even know if I was going to be good enough to do the Integrales, because it's a lot harder than Ionisation, the other Varese piece I conducted."

[...] Mix: How did you interact with the San Francisco Contemporary Music

Players in the rehearsals?

Zappa: Did I tweeze it out? Yeah, I tweezed it. They knew the stuff

very well before I got here; they had played it before. They knew what the notes

were—it was just a matter of spiffing it up. Ultimately, it's up to the musician.

What the conductor is doing is showing where the beat is, and then telling them

things about style to taper it to his own taste. The instructions I gave them

about style were not extensive, because the minute I started conducting them

they sounded like they had a pretty good grasp of what the piece was supposed

to be. The only things I told them, for instance, was how to say certain

parts—don't just play the notes, but make it talk.

Mix: What's your feeling regarding the success of having your name connected

with a program of classical music by other people?

Zappa: Well, I think it helps to sell tickets.

Alain: In an Edgard Varèse tribute you conducted some various compositions, what were they?

FZ: Ionisation and Intégrales.

Alain: Do you plan to make a record of those sessions?

FZ: No. At the time that I did it, I thought that the performances were really good and the only thing that exists is a little cassette that was made in the audience. There wasn't any money, any source to pay for the musicians or recording to do it. But those musicians in San Francisco that played it were very, very good. It's too bad it wasn't recorded because they had the parts well learned, and the tone was good, the rhythm was good—it was a pleasure to conduct them.

DS: In '83, I saw the concert in San Francisco in which you conducted the music of Edgar Varèse . . .

FZ: Um-hm.

DS: I was familiar with those compositions. I had listened to them many times, and, if memory serves me right, even attempted, perhaps futilely, to read a score along with some of that stuff.

FZ: Um-hm.

DS: But when I saw that performance, it gave me a completely new outlook on that music, simply because was able to see how the syncopations were working within that . . .

FZ: In the beat.

DS: . . . within that beat that you were swingin' with the baton. It completely changed my whole perspective on that.

FZ: I happen to think I did a fabulous job conducting those pieces! I have a cassette of it, and from a rhythmic standpoint, I think I'm getting real close to what's on the paper on both of those pieces. There were a couple of things that I didn't like about it, but I thought I did a good job on 'em.

DS: How did you feel the ensemble did?

FZ: Pretty good. I had one rehearsal . . . so . . .

DS: That's kinda jumpin' in the deep end, huh?

FZ: Yeah, well, I rehearsed the score at home, just beating thin air, and I knew what the pieces were supposed to sound like, 'cause I'd been listening to 'em for years, so that part wasn't so hard, but I only had about three hours with these guys the day of the show.

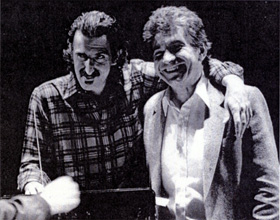

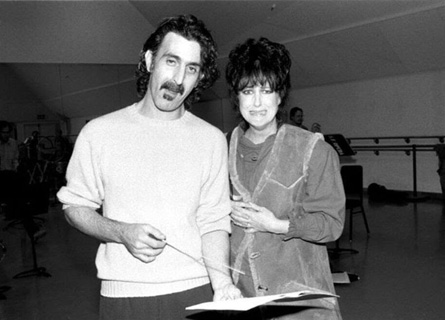

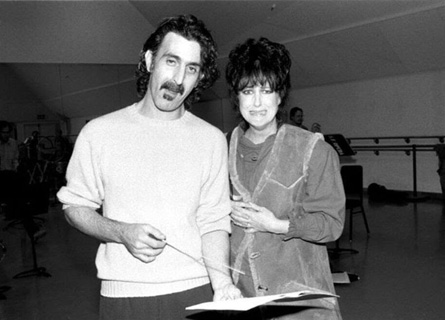

Rehearsals

[FZ, Grace Slick.]

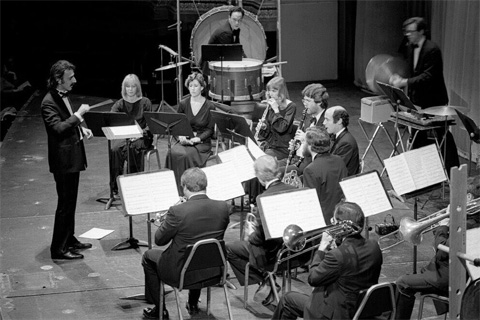

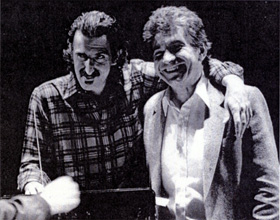

The concert

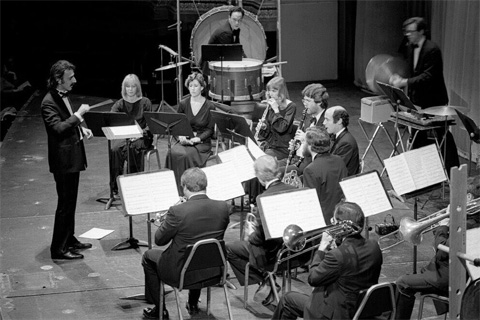

[FZ. San Francisco Contemporary Music Players.]

September 1983—FZ vs. Warner Bros. (Again)

It's a really complicated legal story, and I don't want to recite it again. But the fact of the matter is that part of the lawsuit was settled out of court, and I got all of those masters back; I got all of the tapes back. They're going to be remixed, remastered, and re-released.

Allan Handelman: You won the case from Warner Brothers. That's where it started, right?

FZ: Well, it's not— The thing was settled out of court. It didn't go to a conclusion where one or the other side won. It was settled out of court. And part of the settlement was I've retained the ownership to all of my original masters going all the way back to the beginning. The only album that I don't own is 200 Motels, because that's owned by United Artists. But everything else I have, and I'm going to remix it, remaster it, and put it out in a humungous collection around Christmastime.

Associated Press, September 14, 1983

Rock star Frank Zappa [...] is suing Warner Bros. Records Inc. for $6 million, his lawer says.

Attorney Christina Jacobs says the suit filed Monday in Superior Court charges that Warner Bros. failed to account properly for sales under the 42-year-old entertainer's two records labels, Bizarre Records Inc. and Discreet Records Inc., and seeks $3 million in compensatory damages and another $3 million in punitive damages.

"Frank Zaps 'Em" (unknown origin, reprinted on Mother People #20, October 22, 1983)

Singer Frank Zappa filed a $6 million suit Monday against Warner Bros. Records, charging that the firm's distribution company failed to properly account for the royalties owed him. The Superior Court suit claims Warner failed to account completely for sales and issued false statements to Zappa and his tow companies, Bizarre Records Inc. and Discreet Records Inc., in violation of agreements reaached in 1968 and 1973. The suit seeks an accounting of record earnings, $3 million in compensatory damages and $3 million in punitive damages.

Q: How's the situation with Warner Brothers?

Zappa: I'm still suing them. This is my second suit against them. It was originally started in the state of New York and brought back to the state of California, and will probably be going to trial in about three years. These things take time. The first one lasted seven or eight years, and I've got another suit against CBS which is the same problem, royalties.

In 1983, Zappa sued Warner Bros. Records, alleging that Warner used questionable accounting methods to mislead him about royalties due from sales of his music, a practice he says is still common in the music business. Most artists don't take the time to closely scrutinize their contracts with record companies, Zappa said. But he wanted more control over the sales of his records.

When the suit was settled out of court, ownership of many of the masters reverted to him. Zappa said he spent about $1.6 million on the suit, but the steady sales of his old records are very lucrative. "I have albums that were released 10, 15, 20, 25 years ago that are selling substantial quantities in CD and cassette," he said.

Warner Bros. executives declined to give figures on past sales of Zappa's albums, and they remain touchy about the lawsuit. "I'm not going to deal with any issue relating to Frank Zappa," said a source at the company, who asked that his name not be used. "If we say he sold 2 million records for us, he might come back and sue us for royalties." But the source did say Zappa's records consistently sold hundreds of thousands of units, which "wasn't huge, but it was substantial."

Synclavier

Steve De Furia

The Synclavier came right in the control room. As a matter of fact, Steve De Furia, who was a gentleman from New England Digital, came in to do a demonstration for us. [...] He came in and did an audition with the Synclavier, and Frank saw it as a very usable tool. Something that would be—oh, gee, I don't know—something we could use to implement samples and making good recordings, and all that kind of stuff. [...] So when he auditioned the Synclavier, Frank said, "Well, we need somebody to operate this thing." So he offered Steve De Furia the job. To just come on board with us. And Steve accepted the job. Steve was working with me in the control room when we started going into the so-called Synclavier phase. And him and Frank started doing all kinds of archiving together on the actual Synclavier itself. Heck, we had—at one point, believe it or not, we lost about three months worth of work into that thing, when the Winchester hard drive crashed. It was just a heartbreaker. In those days we still had some of those reliability problems.

We have a trumpet sample in the Synclavier now, and the guy who's programming for me, Steve [De Furia], did a tweeze on it that he calls "wazzing" the note. He set it up so that once the sample is initiated by the keyboard, it starts to rise an octave; and it will go all the way up an octave if you keep your finger on the key long enough. But if you take your finger off, or if you're playing fast lines, the result is this bizarre sort of thwarted linear desire: It keeps trying to rise, but it never gets all the way up to the octave. It makes the strangest effect on the trumpet sounds. I imagine it would do just as well on any string sample. So far we've sampled some great low notes on a Bösendorfer piano, huge bass drums, castanets, snorks, wu-han cymbals, chimes—all kinds of stuff. And you're able to play scales of these things after they're in there, and they sound completely real. It's not like the Fairlight [another digital synthesizer], which, to me, sounds kind of like cardboard when you put things in sample. Synclavier sampling is much more realistic because of the 50k [50,000 cycles per second] sampling rate.

My first experience as a software designer was writing a set of composition programs for Frank Zappa. Those programs got me very deep into computer programming. Before that, I'd never really written any software.

Well, I have had [my Synclavier] for about four years, and when I first got it I probably did the same thing that a lot of people do when they buy a complex piece of equipment—I said, "Oh my God, do I have to read all those big books?" So I didn't! Yes, I can tell you honestly folks that I never did read those big books.

But on the other hand I did happen to hire people who had read them, and they did all the stuff that I didn't want to do.

What I wanted to do right away was write music on it, not learn how to write computer programs. I still don't know how to do that and I will probably never bother to find out, because it took me about two or three months before I could turn round and say, "I can type music into that!"

I remember I had a guy [Steve De Furia] operating the machine and the way it happened was—and, boy, how this man suffered! I was working on a piece and I had to get the musical information into the computer. Since I didn't know how to type it in, I had to sit next to him and say, "Make that one a C, make the next one a G, etc." Then one day he said, "Look Frank . . . if you would just do this, then I wouldn't have to sit here!" So I said "Okay, let me try," and it only took about a day to learn the process. From that point on he couldn't even get into the room to use the machine because I was there day and night!

How did you become interested in the Synclavier?

I read about it in a magazine and then I had somebody bring one over for a demonstration and when I saw what it could do, I bought it, and I also hired the guy who demonstrated it. His name is Steve De Furia.

David Ocker

Steve DeFuria [...] taught me a lot about the Synclavier—and he actually wrote software that we used. In fact, I got switched over from copying to Synclavier because Steve really wasn't available for as much work as Frank wanted done. Steve wrote a column in Keyboard magazine after that for a while.

David [Ocker] is in the process of loading in some stuff on the computer, this composition that I'm working on, so that's very time consuming. Basically, what he's working on is a keyboard piece that is rhythmically pretty close to impossible for a human being to play. But the computer I've got in the other room is doing it very nicely. It's a great sounding piece, but he can only load in two or three minutes a day. I work on it during nights.