A Zappa Affair

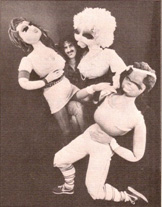

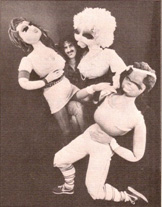

Frank Zappa and Puppets. Photo: Tony Plewik.

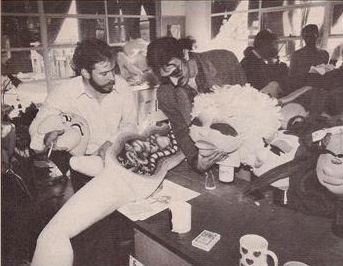

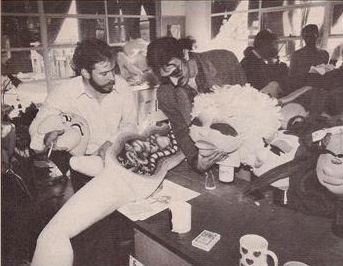

Frank Zappa and John Gilkerson. Photo: Tony Plewik.

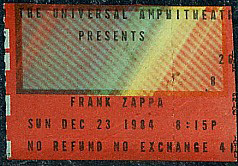

June 15-16, 1984—Zellerbach Auditorium, Berkeley, CA

Two years ago when I first heard of Zappa's pieces for large orchestra, I was working with a ballet company. Kent Nagano, music director and conductor of the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra first brought the works to our attention. It was hoped that the ballet and the symphony would be able to produce the works in a joint concert in the spring of '84. [...]

Both Zappa and Nagano kept the project alive for two years and ultimately, because of financial considerations, the ballet company had to withdraw. In my years at the ballet, I had developed a friendship and admiration for John Gilkerson—a well known Bay Area designer, performer and puppeteer. In early January, John and I met at my home to discuss the expansion of his company, the San Francisco Miniature Theatre. We were casually talking about the demise of the Zappa project with the symphony and the ballet. My head was filled with thoughts of puppetry that night—and in the midst of discussing John's ideas for a full length production of Hans Christian Anderson's Snow Queen, it occurred to me to suggest to Kent that he use John's talents as a puppeteer in the Zappa project. Surprisingly Kent, though initially opposed and concerned about Zappa's reaction to the idea of using puppets, said he would call Zappa that night. John and I spent the rest of the evening discussing the use of the puppets in the four works. We decided they must be large enough to be able to be seen clearly in a large performance space (Zellerbach Auditorium). John's own talents as a performer and his inventive sense of production and staging led to some wonderfully funny solutions to the use of puppets in place of dancers. We knew if Zappa would agree to the idea—that we had something that would surpass the original concept. Well, Zappa loved the idea—and the rest is history, as they say.

John immediately set to work preparing a set of designs for the multitude of characters needed for the production. In all, over 60 life-size and larger-than-life size puppets (one is 14') would be used. Scenic elements would also have to be built for the productions. It was decided to use professional dancers to move the puppets to the choreographed staging of two Bay Area dancer/choreographers, Tandy Beal and Joan Lazarus. After an initial approval by Zappa for John's designs, work began to build 'mock-ups' for an audition to be held in mid-March to choose the dancer-puppeteers. Over 100 Bay Area dancers showed up at the Victoria Theatre on March 19. Initially the dancers were asked to do some choreographed segments to see how well they moved. After five hours of work, twelve dancers were chosen according to their dance backgrounds and abilities. Most important was their skill to project an impression and direct attention to something beyond their actual body movements, i.e.: a puppet attached to them by elastic straps or an object to which their attention was directly focused. The first time I saw the puppets that night—and listened to the reaction of the audience of hopeful dancers roar with laughter—I knew we were involved in a very unique project. I was very excited and impatient to see how the puppets would eventually look. I had to wait until late April at a planned photo session.

Shortly after the audition, the dancers spent one full day getting to 'know' the puppets. It was important that the dancers, so used to moving freely on their own, could be exposed to the complexities of working these huge puppets. It was fun to see the dancers on this first day working with the puppets creating different physical postures. Actual choreography did not start until the first week of May after a great deal of construction on the production was completed. During my visits over the next month or so to John's shop, I was fascinated to observe the artistic process of the building of the puppets step by step. At times the place had an eerie feeling—with bits of bodies strewn all overheads over on one side, stacks of headless bodies in one small room, faces on work tables. Great care was taken to preserve Zappa's artistic control and input and John and his Production Manager, Frank Morales, made several trips to Los Angeles on an on-going basis. John and Zappa worked as a team and the original scenarios were altered slightly as new and funnier as well as more outrageous ideas were thought of by the two.

The puppets, moved by ten of the dancers, are operated by wooden rods connected to various body parts, as in traditional Bunraku (some are operated by as many as five dancers). Some will actually be attached to the dancer's body by elastic straps, moving freely as the dancer moves. It is hard to distinguish any separation in the two figures—one live, one inanimate. Interacting with the dancer-operated, life-size puppets are two male dancers. They will assume different roles in the productions enhancing the biting wit and fun of the scenarios and the effectiveness of the response from the puppets.

The orchestra planned a schedule of over 20 rehearsals to perfect the difficult orchestration. Kent Nagano is comfortable with scoring of this nature, and especially with Zappa. He conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in a recording that Zappa produced last year of three of the works to be presented in A Zappa Affair.

Kelly Johnson, the manager of the Berkeley Symphony, would rather not talk about the "Zappa Affair," which was one of the symphony's most exciting, and most damaging, productions. Johnson would like to forget what he calls the "nightmare of 1984" and concentrate on the very successful current season. It seems as if no one who had a part in the Zappa concerts wants to be reminded of the experience; one past board member says her "blood pressure goes up every time I think about It." Even now, several years after the Zappa extravaganza, people talk about it with hostility and anger.

What went wrong? Why is it a sore point in the symphony's history? After all, the show was a big critical success. The way it combined theater and dance and larger-than-life puppets with Zappa's music produced "one of those rare times," said the Oakland Tribune, "when a wild new concept is fully realized." The San Francisco Examiner called it "an example of exciting and worthwhile theater." But while it was a dazzling and engaging production, It was also an expensive and disorganized one. What began innocently enough as an evening of Zappa's music, played by the Berkeley Symphony, was expanded into a multi-media performance, and the artistic visions of the people who planned it ended up being far too ambitious for the budget.

The Skaggs Foundation gave the symphony $20,000 for the Zappa project, but the grant hardly began to cover expenses. "I saw the budget go from $50,000 to $100,000 to $130,000," says Johnson, who had just assumed the position of manager and found that all the decisions had been made by the time he arrived. Among choreographers Tandy Beal and Joan Lazarus, designer John Gilkerson, conductor Kent Nagano, and Zappa himself, there were bound to be some personality clashes, which hampered the project. The Oakland Ballet was scheduled to perform, and pulled out halfway through the planning stages. After the show, bills were left unpaid, tempers were high, and the Berkeley Symphony was getting a bad reputation. No one could control the budget; the symphony was going hundreds of thousands of dollars into debt. Johnson describes his first few weeks on the job, and the mental strain of receiving nasty phone calls all day long from everyone involved: "I would come to work, get beaten up, and go home; come to work, get beaten up, and go home."

An outside observer, on the other hand, would say that the Berkeley Symphony's "Zappa Affair" was a real coup, and typical of the symphony's adventurous dedication to excellent performances of contemporary music.

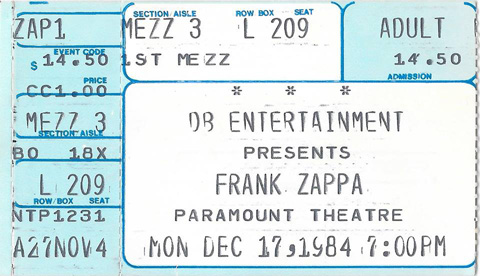

June 20, 1984—San Jose Center For Performing Acts, San Jose, CA (Cancelled)

Gary Worsham, January 4, 2002

The San Jose concerts never occurred. They were cancelled due to lack of ticket sales. Was I the only one who bought one?

The 1984 Tour

[Allan Zavod, Napoleon Murphy Brock, FZ, Chad Wackerman, Ike Willis; Robert Martin, Ray White, Scott Thunes.]

Gear

On the last tour I used two 100-watt Marshalls for main amps and two small Acoustics to run my three MXR digital delays through. The only other effect I use is a stereo chorus.

It's a customized Stratocaster. The only thing on this guitar that is Fender is the body. Everything else on it is custom. It has a custom neck, it has customized electronics, custom pickups, Floyd Rose tremolo.

I just started using this particualr guitar in July, and usually when I go on tour I take a number of guitars and I change them during the show. The ones I brought on the 82 tour I changed a lot. On this tour I just play this one guitar.

Auditions

Frank was looking for a piano player, but he needed someone who was a particularly great reader. Steve DeFuria (his then Synclavier programmer and now VP of Corporate Strategy at Line6, and

one of my oldest friends) and I knew a piano player from our Berklee

days who just moved out to Los Angeles, and we gave Mr. Piano a hearty

recommendation. Frank once again cautioned us that he "had to be a

great reader" and we told him that Mr. Piano was a former Berklee teacher and could read a fly running across a page. Trouble was that

Mr. Piano had a bit of a superiority attitude, which we assumed he

would tone down in the presence of someone so esteemed as Frank Zappa.

Just to be sure that Mr. Piano had a fair chance at the reading part of

the audition, Frank gave him 2 pieces of music to work on a week before

the audition was to take place. One of these pieces is called "The Black Page," which was pretty dense with notes and a real challenge to play.

Challenge enough that Mr. Piano kind of gave up learning it as

precisely as needed and decided he was good enough to wing it during

the audition instead. Fatal mistake #1.

When the audition started Mr. Piano gave Frank a little of his natural

superiority attitude—fatal mistake #2! Frank's acerbic side reared up

and about 4 bars into "The Black Page" he stopped Mr. Piano as said, "Can

you play the song backwards?" Mr. Piano now starts to sweat a little

bit as he realizes that he's in for more than he expected.

After about another 4 bars of playing Frank stops him again and says,

"Can you switch hands so that the right hand is playing the bass clef

and the left hand is playing the treble?" Mr. Piano is now really

obviously nervous since he's way deep in unfamiliar waters (Frank

Zappa's natural environment), his playing is completely inverted, plus

he's still attempting to play the song backwards (from end to finish).

As a result, his attitude comes back to earth in a sudden crash, just

where Frank wants it.

After another rather limp 4 bars Frank comes in for the death blow.

"Can you play the song without using your thumbs?" Now Mr. Piano is a

quivering mass of jelly and can't even get a bar through when he stops

and says to Frank, "That's impossible. No one can play it this way!" To

which Frank replies, "You're a pretty good player, but you're not that

good. I know 3 drummers who can play this with no problem."

And with that, Mr. Piano player was on his way, his ego definitely in a different place than when the day started.

Musicians

IB: What memories do you have of Napoleon Murphy Brock on the 84 tour?

ST: He was great. I loved the way he stayed in bed 'til it was time to leave for our first gig (San Diego? Three-hour drive away.) without even remotely getting his room ready to leave. We out-of-towners (me, Ray White, Napi) were put up at a residency apartment in the San Fernando Valley. Kitchen, utensils and plates. That type of thing. We were there for about three month's worth of rehearsals and so we were very much 'living' there. Napi's room was a fucking mess. We were due to leave at, oh, say, NOON, and I went to go get him and, bless his heart, he was lying there asleep or something. I went in to wrangle him and it was obvious that he wasn't planning on driving with us in the van, but intended to use his own very large old-school boat of an American car to drive himself. Mistake number one. He very seriously completely missed the entire first sound-check. This is a serious no-no and I only did it once in the seven years I played with Frank, and that was for a pretty serious reason (I'd lost my passport) and Frank had even threatened to fine me for it. I told him to go ahead, I couldn't help it. So whatever, dood. He didn't. So for Napi to whip that out at the beginning of the tour was pretty righteous. The next two weeks were repeats of this type of thing. After a while, Frank just figured he was too high to proceed. I have no idea if drugs were involved—I'm just guessing—but you'd have to have a serious priority-issue if you thought that what you were doing was more important than what Frank needed you to do. I wish he'd stayed.

I guess 1984 was probably my least favourite. Allan Zavod was the primary keyboard player on that tour, and he's also a wonderful player. [...] But we didn't have Tommy [Mars] on that tour; not to say anything bad about Allan Zavod. I missed Tommy for his musicianship and his approach.

That was also the first time we went out without percussion. We were doing the MIDI thing, and we had all these DX7s MIDIed together. While that seemed wonderful at the time, the DX7 was kind of a doinky thin little sound and it just wasn't the same as a real marimba. Chad wasn't really using real drums—he had the kick and the snare—but the rest were pads. He didn't even have cymbals, did he? Did he have a real hi-hat? I don't remember; I think he probably did. It was a different sound. Frank was into it; it was like new, but I think the bottom line, when I go back and listen to things from that tour, the sound of the band just wasn't . . . [...]

There were personnel problems. We had too many singers at first for one thing. The band for the first couple of weeks of the tour was different from then on. We had Napoleon Murphy Brock back in the band in the beginning, and Ray and Ike and Frank and myself, so we had five people that could really sing; well, if you include Frank in that (laughs). Four people who could really sing and Frank. It was just too much. What we did was they put me up one inversion higher from all the harmonies I used to sing, so now instead of a triad with Frank, Ray and me which was the 1981 tour, it was Frank, Ike, Ray and me, with me singing an octave higher than Frank's parts all the time, so it was a triad plus an octave. Not that I couldn't do it, but it was 'Why do we need to do this?' Some things I wasn't singing because Nappy was there, and one of us had to drop out because it was just too many. It did make possible some interesting things vocally from time to time. But there was some friction with Nappy and some of the other guys and he ended up leaving. The rest of the tour continued with everyone else. [...]

We also had a problem with the repertoire. I remember one night, Scott Thunes and I ganged up on Allan—I think it was in Munich. We took him out to one of these big beer halls and sat him down and said 'Look Allan, we got to learn some more stuff, because we were getting tired of playing the same stuff all the time. He didn't have enough of the repertoire learned and memorised to enable us to do what we normally did. By the end of most of the other tours, we would have as many as like two hundred pieces that we could select from. Not just stupid little songs, but Zappa songs. That wasn't happening in 1984. So we kind of prevailed upon Allan to get some more stuff going, and by the end of the tour, it did improve a bit, but that kind of slowed things down a bit. That was one of the drawbacks of that tour.

Ed Mann

Q: What happened in 1980 and 1984?

E: 1980 I was drumming. Those bands, he didn't want percussion in them. No actually, 1980 I was doing another project. '84 was when we started this band with Vida [Vierra] and Mike Hoffmann. It was a different concept, you know. I went to see the band and I thought 'It needs percussion'.

Tommy Mars

Well, '84 . . . I really don't know what happened. I was having a problem with Scott Thunes to be perfectly honest. Nothing against Scott, but I just didn't want to go on the road. It was around the time that I started to become a painter, a fine artist. I started getting really very disenchanted with the music biznis. I was getting a desire to paint a lot more. I was tired of going on the road and decided not to do it.

Napoleon Murphy Brock

Alain: What did happen with Napoleon Murphy Brock?

FZ: I gave him chance to be back in the band and he failed. So I had to fire him in the middle of the tour.

IB: I was going to ask you about the 84 tour. As you say, it was a short tour for you.

NMB: Yeah, I could only do the short American leg. I couldn't do Europe and the rest of the tour. When we got back together for the Thing-Fish album and some things for Them Or Us, Frank said "Why don't you come and do the tour with us?" And I said, "Well I can't do the whole thing, but I'll do what I can."

IB: I don't think he released any recordings from that early part of the tour. He's released lots from the subsequent part, and I have to say it's some of my least favourite stuff. So I'd loved to have heard you with them.

NMB: He was trying so hard to keep them happy. I was playing flute, alto sax, tenor sax, and baritone sax. So I wasn't doing a lot of singing.

[...]

The last time I spoke to Frank was when I finished the 84 tour.

Brad Cole

Scott Thunes, January 23-25, 2002

[...] Brad Cole was 'in the band' as far as I was concerned at that point ["Be In My Video" recording session]. He was GREAT and I was TOTALLY DEPRESSED to find that he was going back with Phil Collins for TONS MORE MONEY than Frank was offering. One of my favorite pieces at that point in my life was the Bartok Piano Concerto No. 2. He played me the cadenza from the first movement and I wanted to fuck him right there in the studio. He quit just a little while after that and RUINED the 84 tour by having Frank hire AZ. RUINED!!!

[Brad Cole] passed an auditon for Gino Vanelli—a musician's musician, who at the time was at the height of his success. [...] But when Vanelli's popularity was on the wane he found himself back to the club dates and casuals once again, backing a string of nostalgia acts such as Helen Reddy, Englebert Humperdinck and Donny and Marie Osmond.

The experience with Vanelli, however, did afford him the opportunity of playing alongside other respected musicians on the LA scene and consequently getting his name 'out there', an all-important element in the session musician's networking game. It was through this band that he first met Genesis guitarist Daryl Stuermer who would later be instrumental in his recruitment into Phil Collins' band. But that wouldn't be for another ten years. Meantime, the late rock 'n' roll genius Frank Zappa was knocking at his door.

"One weekend I went from playing with Donny and Marie Osmond in some little theatre somewhere to the next day flying home and having an audition with Frank Zappa. I thought that was the epitome of going from one extreme to another," he laughs.

Such is the life of a session musician, never quite knowing what's around the next corner. In fact, Brad got the Zappa gig contributing keyboard parts to his 1984 album Them Or Us, but subsequently twice turned down offers to become a permanent member of Zappa's backing band in favour of a Supertramp tour and a string recording session in LA with mainstream established artists such as Michael Bolton, Natalie Cole and Lionel Richie.

You turned down another pretty huge crazy gig.

This was this the all-time mash-up—music business mash-up, because I went from a Saturday night gig with Donnie and Marie at some like dinner theater kind of place in the midwest, fly back to L.A. and go out to Frank Zappa's house for an audition, and I did—I auditioned for Frank and much to my amazement he was going to hire me. And I wasn't expecting that and I had a panic attack over it 'cause I thought, "Now I have to actually deliver and that's when he's going to find out that I suck" And I had to say no, I turned it down.

And you know, people thought I was insane, and I think I was insane in some ways, but I just wasn't emotionally strong enough to do that at the time. I regret it because it would have been the experience of a lifetime but—

Was he intimidating?

No. He was great. He was—Everything you would want Frank Zappe to be, he was. And he was— The audition was so much fun because it was—I figured immediately I was not going to get this 'cause the guys who came before me were monsters. Monsters. I knew—I had gone to school with one of them, Tommy Mars. He and I had the same piano teacher for a long time. Tommy was just living in another astral plane somewhere, as a player and as a human being. He was just somewhere else and I thought, "I'm much too ordinary for a gig like this and, you know, I'm not entertaining enough, I'm not weird enough, but I know if I get the gig I'm gonna become that," and I got kind of frightened by that. 'Cause I thought, "I can't handle—I can't even handle being ordinary, that's difficult enough." But being weird would probably, you know, that would be it, you know.

But the audition was fantastic because not, not or at least believing I wasn't going to get it I just wasn't nervous about it, I was just having fun thinking, "Oh, this is what these auditions are like, I've heard about them, here I am in one!" And the highlight was he wanted me to play play— He says, "Do you, can you play any TV themes?" Now that's not your usual request at an audition. And I thought for a minute and I said, "Yeah! How about Perry Mason?" I play Perry Mason. He goes, "Okay, that's all right. Now, can you do it as a— Do it as a reggae." And I right away knew where he was going, he wanted to see how flexible I was, and I just laughed because I thought, "That's exactly what you think Frank Zappa would ask and he just asked it." So I did it. I played Perry Mason with a reggae beat and all that. He goes, "Okay, now, now do it as Mozart." You know, he was pushing, pushing the boundaries. So I laughed again, I just thought, "This is great, so cool!" And I tried as best I could to play, you know, a classical version of the Perry Mason theme and I thought, "Well, this is good." I nailed that. He goes, "Now play it like Mozart with a reggae feel." Mozart with a reggae feel! I laughed the most at that 'cause I thought, "There's no limit to where this can go!" And that's the whole point, he wanted to see how malleable and flexible my musical mind was. I thought, "That's great, that's, that's what I like too." So I tried it—I'm laughing while I'm doing it because this is ridiculous idea, you know.

And the next thing I know he's offering me the gig. And I was— I was really, as they say, without speech. Speechless. 'Cause I wasn't expecting anything close to that. So I had to— I said, "I don't know, let me think about it." And that's not what you're supposed to say, you're supposed to say, "Yes! Yes! Please!" But he was wonderful about it, and he gave me a little consolation prize—he let me play on one of the tracks on the album he was working on, and it was a song called "Be In My Video"—and there was actual video for it, which you can find on YouTube . And it was one of his kind of like a snarky kind of parody songs of the time, making fun of the video culture. And the piano part was as Liberace as you can get. That was the instruction he gave me. "Just as, as, you know, stupidly over the top Liberace as you can do." And I started playing all these arpeggios and just, you know, really tasteless stuff. And he came out after one of the takes and he goes, "You're the perfect guy for this song." And I said, "Thank you, I think," I don't—you know. I actually thought about that for months as to whether that was a compliment or not. But nevertheless I'm on a Frank Zappa album.

But all, you know, what he wanted most to talk about was Donnie and Marie. He was itching to get details on them, 'cause he understood immediately that, the implications of having somebody who just come, comes out of this schlock world into his world. It's like an alien coming to the planet, you know. And that's—we just talked about Donnie and Marie for a long, long time, and I told him Donnie and Marie stories and things that happened to us in the road and all that stuff. He just ate it up with a spoon, he loved it. So that may have had— you know the thing about Frank was he was casting his band the way you cast a movie—everybody has a character. And my character might have been the stupid Poindexter from the straight world, that might have been what he had in mind for me. I didn't come to that realization till years later, but maybe that's what it was and I wouldn't have had to have been such a chopster.

Informant: billf (Zappateers, October 22, 2024).

Allan Zavod

His name was Chase. He was the road manager for Jean Luc Ponty when I first joined Jean Luc Ponty. They had a few managers but he was the first one. I was out of Ponty for eight years and I hadn't seen Chase for maybe six years. And I don't know how he found me, but I was in Arizona, I'd just come back from the Grand Canyon, with my father. My father came to visit me in the US; he said we'd go for a holiday. My girlfriend lived in Phoenix, Arizona. So my father and I went to Phoenix, put our bags down, took the car and went to the Grand Canyon, just the two of us. Then we got back, got into bed, we were tired after three or four days of traveling and the phone rang.

How did this man find me? It's eight o'clock at night and he says: Frank's looking for a keyboard player and I know you're the guy. You're the guy, you're the right person! Get to L.A.! Here's Frank's number. So I called Frank. He gets on the phone right away. He knew who I was because I'd been with Jean Luc Ponty, he'd followed my career. I didn't know that. So he gets to the phone and he says: Can you come now to L.A.?

In those days (it was in '84) the airlines only flew till 7.30, now they fly in each hour. I was an eight hour drive away from L.A. so I said: I can't fly but I have a car, I'm gonna get there for two o'clock, why don't we do it tomorrow? He said: no, no, come now. OK, then.

Nine o'clock I'm on the road with my father, we're driving and about twelve o'clock we're still not there, so I called Frank again and I said: Look, I wanna be good for the audition, I'd be so tired, maybe we'd do it tomorrow. No, come now, you have to come now. Don't worry if you're tired, I understand. So I get into car and I said to my father: Dad, I have to get some sleep, you have to drive. My father had never driven in America. So, he's driving on the freeways of L.A. and I'm sleeping, I got a one hour sleep, which was good.

We got there three o'clock in the morning, Frank was there, the whole band was there because they said this guy must be good, if the boss is stayin', we're gonna stay, we're gonna check this guy out. Some of them knew me anyway. I had my father with me so it looked good, you know, good family upbringing, Frank was a big family man.

And he puts the most impossible music—Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch—can't read it, he was making a joke. I tried. He took the music and said I can see you can read and then he said: we'll play. So we just played a couple of chords. I was playing with everything I've got and he liked that. I could see they were all smiling and he was looking and smiling at his band so I got more confident and then he played and I accompanied him. Then he stops the band and he says: Excuse me, he says, can you hear me? Very rude. He was just testing—can I take his personality, will I fit into his band? He's already made up his mind, but he wanted to test me, checking out my vibe. So I said nicely, yes I can hear you very well. He says you're playing too many notes. So I played beautifully. So now he knew he could give me orders and that I could understand them and that I was strong, so he could rely on me to give him information. He wanted me to give him ideas, too. Frank Zappa was very strong but he always looked for others too around him for ideas. He wanted to bring out the best in everybody and sometimes on the tour I'd play something and he'd say listen to this idea or some other. He would always go for the challenge.

Anyway, so we played and he said: OK, we'd like to have you. The only time in the whole history of Frank Zappa ever did he give the job on the spot right away, except for me and George Duke. Normally he would say we'll call you or we'll let you know. He was looking for something. I know what he was looking for. He needed someone who was classically trained and jazz trained, good rock deal, someone who would be able to be new at something, research it and get it. The keyboarders at Frank Zappa's band were very important, especially me. I had to anchor the band. The strong harmony, pulling it together was very important and you had to be able to accompany. The last keyboard player who played—Tommy Mars—couldn't accompany very well. He was great, he knew all the material but he couldn't accompany very well. Frank used to say when I solo, don't play. But with me, because I was jazz trained—I'd been with Woody Herman, Glen Miller, Maynard Ferguson, Jean Luc Ponty—I studied and taught at Berkley, so I knew my stuff. We'd have a terrific relationship. Nothing bad to say about Tommy, he was a fantastic musician, but they wanted something different this time.

[...]

Every night on tour I'd go to my hotel room and then next day whatever I'd learned we'd rehearse. We never had a sound check, it was always rehearsal. Sure you tried the instruments, but we rehearsed for two hours every day before the gig. And if the rehearsal went well, that night it would be on the list. See, every night we'd play a different program, different order and different things. We always had a meeting before the show and he would say: This is what we'll play. So we never knew what we'd gonna play. It was always up to me, whatever I could learn, they would play, it was a lot of pressure.

July 24, 1984—Open Air Amphitheater, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA

Last call: a warm July evening in 1984, still in San Diego, but outdoors this time. Napoleon was back! (Not for long, though.) Up there with Ike and Ray, having entirely too much fun, occasionally flopping on their bellies when FZ would invoke the night's secret word, "matches." (You need to bring some if you want to use the toilet after Ray's been in there.) Frank began by requesting that anyone within earshot who would be made to vomit or to go to Hell by the use of bad words should leave, and to give them time to do so, he would play an instrumental. And so, perched on a stool as the sun faded, Zappa lit into a smoldering "Zoot Allures." The show that followed had more buffoonery than the others I'd seen: abusing a Raggedy Ann doll during "Honey Don't You Want A Man Like Me," brandishing an oversized glove for "Oh No" ("You think that you really know the meaning of glove...You say glove is all you need..."). Napi did his operatic "Evil Prince" aria. An uncharacteristically wistful Frank concluded the show by noting "This is a nice place. I like playing here."

Sadly, he never came back.

September 13, 1984—Drammenshallen, Drammen, Norway

Michael Brenna, "The Spoo Show," Society Pages #22, November 1984

"Welcome to Drammin . . . drammln-drammin-hollin-hollin-hollin-hollln!" are Frank's first words tonight. [...]

The compulsory opening instrumental and guitar solo is ["Chunga's Revenge"], featuring Frank on his Fender, which he will use for every solo during the concert. Thls number also features Bobby Martin on French horn. He played alpenhorn on the US tour this summer, but didn't bring it with him to Europe. He hopes to purchase another one in Switzerland, though.

[...] Some other guy in the band said Frank wasn't too satisfied with Alan [Zavod] on the fast complex stuff, no matter how good a jazz musician he might be. So this might well be his only tour with Zappa, as far as we understand.

[...] No recording truck was brought along for the European part of the tour, but recording equipment will be rented for the London Odeon Hammersmith concerts. Hopefully those performances will be as inspired as this one is.

[...] Before the second and last encore things really start happening. Some funny noises are made by the various musicians and Ike tries to impress with a rather abortive feedback on his guitar. Frank thinks this is very funny and goes "SPOO! . . . oh no, terriffic!", and the whole band cracks up and launches into this evenings version: "Dancing Spoo." Frank had to explan the word to me after the show. He gave a definition in his well-known exact way: "When you jerk off and manage too keep quiet, spoo is the little sound the white stuff makes when it comes out." The bar monologue at the end of the song is modified to "what are you doing here in Drammin-drammin-d rammin-hollin-hollin-hollin, love your spoo . . . " etc.

[...] According to Frank the concert was videotaped, and he might edit pieces of it into the video he'll make after this whole tour in February.

In Norway, we have played several times in a place called the Drammenshallen, or, as band vets refer to it: the Drammin-drammin-drammin-drammin-hollin-hollin-hollin-hollin. The last time we performed there was in the fall of 1984.

Some months before that date, Ike had used the word 'spoo'—roughly the equivalent of jizz—in a conversation. I don't know where it came from, or if he made it up. In any event, 'spoo' turned out to be 'the mystery word' onstage that night.

When we came back to do the encore, Ike arrived first, and was kneeling down in front of his amplifier, doing kind of a low-rent Jimi Hendrix "wee-wee-wee-wee." As I walked out and witnessed this act of near desperation, I said "Spoo!" to him—he got it right away. [Translation: "You're jerking off in front of your amplifier, Dr. Willis, and I know it."]