US Tour—September-December 1977

FZ, Press Information for the ZAPPA 1977-78 concert season

Concurrent with the release of "LATHER" (pronounced "Leather"), perhaps the most incredible album ever to be made available for universal consumption, the 1977-78 CONCERT SEASON brings to the bored & miserable people of this curious little planet a live-in-person musical experience of unexcelled quality, combined with the usual dreadful & generally tasteless stage antics of myself & various other people (too evolved to cram the ol' safety pin through the cheek, but rude enough to do those things that make for colorful concert reviews when you need a little something to get the readers' minds off the music . . . what the hey . . .), and so, without further ado, some statistics with which to fill those other nasty little vacancies in your impending story:

FRANK ZAPPA lead guitar, vocals, press kit

ADRIAN BELEW rhythm guitar, vocals

PETER WOLF keyboards, butter

TOMMY MARS keyboards, vocals

ED MANN percussion, vocals

PATRICK O'HEARN bass, vocals

TERRY BOZZIO drums, vocalsThe activities of the above mentioned virtuosi are made possible by:

BENNETT GLOTZER our new manager

PAUL HOF our same old stage manager

DAVEY MOIRE sound mixer (audience)

AL SANTOS sound mixer (stage)

COY FEATHERSTON lighting design

TEX ABEL choreography, fashion advice

LEON RODRIGUEZ divine assistance to all

LEE HAUSMAN power distribution

THOMAS NORDEGG keyboard maintenance & card tricks

ALAN BARCLAY electronic design

JOHN SMOTHERS security(plus an as yet undisclosed couple of truck drivers and bus pilot)

KENNY "PONCHO" LYONS drayage

Keyboards

FZ, interviewed by Michael Davis, Keyboard Magazine, June 1980

Q: Why did you decide to go with two keyboard players at this time?

FZ: Because of the orchestrational possibilities. When George Duke was in the band, a second keyboard player would have been a waste of time, partly because of the type of stuff we were doing. George is so diverse; he can play just about any style, and he's got the discipline to play parts. He really understands how to comp; he's a really well rounded musician. But people like George don't grow on trees. Sometimes to replace the guy who is so diverse, you need two guys who can fit into each other's liabilities. [...]

Q: Do you prefer to use synthesizers now instead of horn sections, or does it depend on the type of music involved?

FZ: It depends on the type of music. For instance, if you are playing a synthesizer that makes a brass ensemble sound and you take six fingers and make a six-note chord and it comes out in tune and loud enough to compete with electric guitars, then you are doing the right thing. For two reasons: One, it's easier to get a balance acoustically, and two, chords and things like that really tire out brass players over a long period of time. Just playing whole-notes is a real boring job for a brass player. It always sounds good, but they always hate to do it because horn players too like to play a million notes. There isn't a horn player alive that likes to play background harmony for a guitar player. They just don't like that, and ultimately they hate their lives; you take them on the road and no matter how much money you pay them, they don't like their lives because they're not out there noodling away. You begin to feel sorry for them, and that brings you down. You feel that you can't play for too long because those guys on horns are going to go to sleep back there. So that's one of the best things about a brass-sounding synthesizer: You can get a brass-like sound in a live performance without breaking the hearts of a number of people who blow on things.

Adrian Belew

Noë Goldwasser, "Zappa's Inferno," Guitar World, April 1987

How about Adrian Belew?

I found Adrian working in a bar in Memphis, Tennessee. He was working in a bar band. They were all dressed like the Godfather. They had, you know, fake mob-type suits on and stuff and he was doing Roy Orbison imitations.I never would have thought of him like that. Did you hire him on the spot?

No. I don't hire people right away. I give them a chance to audition.Was he always into that Hendrix thing, or did he develop it later?

He was doing some of it at that show.

Adrian Belew on Guitar Magazine, February 1994

I was in a bar band in Nashville playing covers of Bowie and Rolling Stones tunes. Frank was in town and asked the chauffeur to take him to see a good band. Well, we happened to be the chauffer's favorite band, so he brought Frank to see us. I saw him walk in from the back and just watch us, which made me a little nervous. In the middle of "Gimme Shelter," he came up to the side of the stage and reached over and shook my hand. Later he got my name and number from the chauffeur, and not too long after that he gave me a call to come audition for him.

This was in 1977, I was familiar with some of Frank's work, but I had never played it. I borrowed a bunch of his records from a friend and then realized how hard it was to play. Trying to figure it all out, I never thought that I would pass the audition. When I got to Frank's it was the day they were installing the studio, so I'm standing there in the middle of these movers and electricians running around. I'm trying to concentrate on playing well and Frank's on the other side of the room with all these people moving stuff in and around us. I knew that I had done a bad job by the time I finished, so before Frank could tell me that it wasn't going to work I said to him, "Look, I can play much better than this, give me another chance in a quieter setting." So we went upstairs to another room and he sat on the couch and I redid the audition. That time, I knew I played well and Frank gave me the job.

We began three months of rehearsal, and it was pretty tough rehearsal. Ten hours a day, five days a week. I'd spend my weekends with Frank, and he'd prep me before the week's rehearsals, so that I was ready when we went to play with everybody else. I needed a little more coaching than everybody else.

Adrian Belew, interviewed by Gary Marks, T'Mershi Duween, August 1994

I had played in a number of bands and ending up joining a band in Nashville that just played other people's music, but it was a rather interesting band called Sweetheart. I was writing my own material, but the band didn't do that. It was more a band that just played a lot of club dates. We were located in Nashville but didn't often play there. We mostly played around the Mid West. So there I was, floundering in this band (laughs) and Frank had played a concert in Nashville. He was looking for something to do afterwards, and asked his chauffeur where to go. He said, "Well; I like this band playing over at Fanny's," so Frank and his entourage, including John Smothers, Patrick O'Hearn and Terry Bozzio came on over, this strange interesting exotic looking bunch of people. I saw him walk in as I was playing. It was undeniable that it was him, and you know I just lit up like a neon sign, because I played and sang better than I ever had done that night.

[...] It was a total surprise. You could almost tell from the audience that something unusual was happening; there was a real buzz in the air. Frank sat and listened to us for about forty minutes, then he came up and shook my hand in the middle of a song, "Gimme Shelter." He said he would get my number from his chauffeur and audition me some time later. It was about six months before he called and I thought he had forgotten about me, but he'd been out finishing off the tour. So then I auditioned at his house and the rest is history.

[...] I think [the rest of the band] were all genuinely excited for me, but as the months went by, everyone thought it wouldn't happen, and nothing would come of it. The band fizzled out anyway. At about the time Frank called, I had nothing to do. It was a pretty low point for me. I was behind in the rent and just about to go crazy (laughs) when I got this wonderful call saying, "Hi, this is Frank Zappa; I want you to come and have your audition. Here's some songs for you to learn." I don't read or write properly, so he just gave me a bunch of songs and said to try to figure them out, to sing and play them as best I could, and I worked probably sixteen hours a day for the next week.

[...] I did two auditions really because I was so nervous at the first one. I was up at Frank's house; there were people moving pianos and other equipment, and there was me in the middle of the room with a little naked microphone standing there, singing Frank's songs. He was sitting behind a studio board, smoking a cigarette and just said, "Play this; play that," and "No, that's not right; play this one," so it was very nerve-wracking. I stood around the rest of the day, watching other people audition, I actually watched Tommy Mars audition. Incidentally, Frank told me later that he had auditioned fifty guitar players, so I felt lucky to get it. Near the end of the day, I finally caught Frank's eye and said, "Frank, I know I didn't do very well, and it's because I thought we would do this differently. I thought we would sit down somewhere quietly, just you and me and I could play the songs and show you I can do it." He said, "Well fine. Let's go up to the living-room and sit on the couch and we'll do that." So I did the audition a second time; then he shook my hand and said, "You got the job."

Q: How did you feel?

AB: I felt like a million dollars (laughs). I was so happy I couldn't believe it.Q: How long was it after the audition that you were on stage with him?

AB : We rehearsed for three months solid before we ever went on stage and it was a very intense, educational period for me. I worked five days a week with Frank and the band, then on weekends I would go up to his house and start working on next week's songs. In other words, he would give me a chance to start learning them by rote before he would show them to the rest of the guys. So I literally spent seven days a week for three months learning Frank Zappa material and staying at his house, working to the wee hours of the morning with him. Hard work, but I loved every minute of it. It was a great time for me. I will always have nothing but great things to say about him because he was always really great with me. I know other people say he was demanding or hard to work with; yes he was demanding but to me it was always a joy.

Adrian Belew, interviewed by Richard Abowitz, "The Universe Of Frank Zappa," Gadfly, May 1999

I was a starving musician and I suddenly got a call from Frank Zappa. He was very nice to me, and he said, "Well, here is a list of songs." He learned at that point that I didn't read music. All the other musicians he was intending to hire read music, but he still gave me a chance. He gave me a list of songs. I worked feverishly twelve hours a day to try and figure out these songs. Frank's advice to me was simply figure out how to sing and play these songs anyway you can. He then flew me to his house in Hollywood Hills. It was very scary for me, because first of all there was a lot of confusion, a lot of things happening, people were rolling equipment, and here is me standing in the middle of a room with Frank Zappa sitting behind a console smoking a cigarette. Frank would say, "Okay, play this," and then I would try to play it, and he would say, "Okay, try this one." I didn't think it went very well. I stayed there at his house for the rest of the day. I watched him audition a lot of great players, including some of the players that I ended up playing with, Tommy Mars and Ed Mann. It was tremendously hard material that everyone was being asked to play. The rest of the people came in and sight read. It was interesting to see these great musicians being put through their paces by Frank. At the end of the day, after everyone had left and I was still there, I said to Frank, "Hey, you know, I don't feel like I did very well, and that's because I really thought that you and I could just sit down somewhere quietly and I could show you that I can play and sing these songs." He said, "Fine, let's do that, then." So we went upstairs into his living room. We sat on the couch together. I had a little tiny practice amp face down on the couch so it wouldn't be very loud and I did the second audition, at the end of which he shook my hand and said, "You've got the job."

Adrian Belew, Guitarhoo!, April 16, 2004

I was playing here in Nashville. I lived here in the 70's for a couple of years and I played with a band called "Sweetheart". It was a 5 piece band; Saxophone, keyboards, bass, drums, guitar, three singers. Three of us sang I should say, haha. And it was a good band. It was colorful. We dressed in vintage 40's clothing. I wore Fedora hats and ties everywhere we went. It was a band that had a little bit of a following. They played really only just cover music. Things like Stevie Wonder, Steely Dan, the music of that era.

And we were playing one night in a dark, dank bar called Fanny's which is now a parking lot here in Nashville and Frank had played a concert. He was looking for somewhere to go afterwards with his entourage with a few of the band members and some crew people. And they had a limousine, the limo driver, his name was Terry, was a fan of our band so he directed him to the night club called Fanny's. They came in and listened for about 40 minutes, then Frank came up to the edge of the stage, reached out and grabbed my hand, shook it and said, "I'll get your information from the chauffeur and I'll audition you when I finish this tour." About 4 or 5 months went by before the call actually came and by then of course everybody all thought it was just a fluke, especially me. But then he called and he said, you know, "Here's some songs I want you to learn from these records and I'm going to fly you out to my place and audition you."

Now as the audition went, it was pretty hairy, uh, first of all I don't read music. I had to learn everything by rote, had to figure out as Frank told me, "Play and sing whatever you can figure out, play and sing." So I learned those records and I really dedicated myself to that. [...] It was very complicated music for me at the time because I had never really played anything outside of popular music really. I mean I hadn't really understood odd time signatures and things like that, although I had an ear for it.

So I went to the audition in Franks basement. It was very unnerving 'cause people were moving equipment around, lots of things were happening. I was standing in the middle of the room with a microphone, a pignose amp and a stratocaster and Frank was sitting behind a recording board saying, "Play this." Then he'd stop and say, "ok, stop and try this." and so on and it went that way and all kinds of choas surrounding me. I felt very uncomfortable and didn't feel I did well. And he auditioned 50 guitar players. [...] I didn't see any of the auditions for the guitarists. I only saw some of the keyboard players and percussionists audition and they were tremendously tough auditions for them.

So I was there at his house, I had nowhere to go. So, I stayed around and watched the auditions all day then when the day was over I finally got a moment to say to Frank, "Hey Frank, you know I don't feel I did well in my audition but it's not the way I was expecting it to be. I thought we'd just sit down somewhere quietly and I would play these things for you." [...] And he said, "Well, let's go upstairs and sit in the living room and we'll do that."

We sat upstairs on his purple couch and I did a second audition just sitting right there next to him and that was very successful.

Uh, pretty soon he was mentioning things and you know showing me different harmonies and stuff, you know. Then he reached out his hand and said, "Well, you've got the job and here's what I pay and here's the rules.", and so on. He ws very straight forward, just a verbal agreement, for one year. [...] He said, "This is a one year agreement." That's how he did it, year by year with his players. And he had different rates for whether you were rehearsing, there was a rate. There was a rate if you were recording. There was a rate if you were touring. Filming had another rate, you know. So basically it was a pay scale and it was more money then I'd ever made, haha... I was thrilled about it of course.

Adrian Belew, interviewed by James Santiago and Daryl Trombino, Virtual Guitar Magazine, 1999

I lived Nashville for two and a half years in the '70s. I played with a band called Sweetheart. It was a good band, and it attracted a lot of attention and stuff. It was a cover band, but we had a unique look and a unique style of doing these songs. Frank came in and saw the band play for 40 minutes, came up and shook my hand and said, "I'm going to audition you. I'll get your name from the chauffeur." That's what happened. Then I flew out here to California for my first time ever, went to his house and did an audition. There were, I guess, 50 guitar players, supposedly. And then I got the gig. Then, you know, really for that first year that I worked with Frank, I stuck beside him like glue. I used to go to his house every weekend. We rehearsed all week, five days a week, but on Friday night I went home with him. I stayed with him at his house so he could show me what was going on the next week and get me started. [...] I was the only guy in the band who didn't read music. So in order for me to learn it, I would start ahead of everyone else. On Monday mornings they would get sheet music, but I would sort of already know what was coming up by then. That lasted for three months. So I felt like in those three months I really got to know Frank very well, and lived at his house and got to know his family and thing. It was a great experience. And then we went on tour all through the states and Europe.

[...] I was also the person who introduced everyone I knew to the Roland [JC-120] Jazz Chorus Amps, including Frank. I heard the Roland at a party I went to when I was rehearsing with Frank, and I said, "You've got to hear this new amp," and they brought some over. That's when I started with them.

Adrian Belew, interviewed by Matthew Shapiro, State Of Mind Music, November 1, 2008

Frank for me was my first and only official schooling. I'm a self-taught musician. I don't read or write music or dots on paper. I was the only guy in the band that way; everyone else was a reader. So‚ they got sheet music. It meant that I had to really pay close attention in practice and I had to memorize a lot. I had to work close with Frank‚ and I got close with him. I would work with him on the weekends in between rehearsals that would last all week. It was a great year for me because of that factor. I was able to absorb so much practical knowledge—not just musical knowledge‚ but all this other knowledge that you would gather from around the world from touring and making records.

[...] I read about how he used to stay at a different hotel than the rest of the band. But with you it seems like it was a lot different.

Yeah‚ he didn't treat me that way. He sort of took me under his wing. Actually‚ the people that didn't want to hang with me was the band. They didn't care too much about me. So‚ I hung with Frank all the time‚ and‚ like I said‚ he took me under his wing and it was really generous. I felt a little like a teacher's pet‚ but I felt like this was my opportunity and I want to learn as much I can from this guy who is a genius. You don't get around that everyday! [laughs]

Adrian Belew, interviewed by Max Mobley, Crawdaddy, June 10, 2009

I moved here to Nashville back in the mid-'70s to play with a particular band, a regional band that did a lot of work and was well-known, called Sweetheart, and they wore 1940s authentic vintage clothing everywhere. If you were in Sweetheart, you had to wear your 1940s three-piece suit with a fedora, even if you were just shopping at Kroger's at two in the afternoon. They were a very good cover band and they did songs that were not your normal fare—a lot of Steely Dan, Stevie Wonder, McCartney and Wings—stuff that you wouldn't be ashamed to play. Anyway, Frank Zappa played Nashville, and after his concert, he had a chauffeur and a limo, and he asked the limo driver, whose name was Terrance Pugh, where would he go to hear some good rock music. And Terrance said, "Well, my favorite band is playing over here in this little biker bar called Fanny's," and Zappa said, "Okay, let's go." So I was standing on stage playing, and suddenly I saw Frank Zappa with his big bodyguard, John [Smothers], and Terry Bozzio. They walked in and listened to us for 40 minutes, then Frank came up and shook my hand while we were playing "Gimme Shelter" and he said, "I'll get your name and number from the chauffeur and when my tour is over, I'm going to audition you."

FZ, interviewed by Tom Mulhern, Guitar Player, February 1983

Adrian Belew, I thought, had potential to add something to the band as it was constituted at that time, which was kind of a funny band. We blew out a lot of comedy stuff like "Punky's Whips." That was the band that originated "Broken Hearts Are for Assholes," and that kind of material. And Adrian just fit in with that, and so that's why he got the job.

Adrian Belew, interviewing Steve Vai, Guitar For The Practicing Musician, January 1994

ADRIAN: Frank is blatantly straightforward and honest. That's one of the things that first appealed to me about him. When I passed the audition with him he shook my hand and said here's how much I pay, here's how much I expect from you, and that was it. There was never any bullshit to have to work through.

STEVE: No contracts, no lawyers. None of that shit.

Adrian Belew, interviewed by Jimmie Leslie, Guitar Player, December 2005

"I was playing in a little Nashville club called Fanny's, and I had just begun sneaking noises into the cover songs we did," recalls the affable Adrian Belew. "All of a sudden, you'd hear the sound of a car horn, and you'd wonder where it was coming from. Ironically, the place is now a parking lot! Frank Zappa played a show in town one night, and he was looking to check out a local band after his gig, as he often did. Frank learned from the chauffer that his favorite band was playing at Fanny's, so Frank showed up with a large entourage that included Terry Bozzio. It was obvious to everyone that Frank Zappa was there.

"It was a special night and I lit up—playing and singing my best. Our band did covers by Stevie Wonder, Steely Dan, and other stuff like that. Forty minutes into the set, while we were playing 'Gimmie Shelter,' Frank reached up, shook my hand, and said, 'Hey, do you want to audition for my band? I'll get your name from the chauffer and I'll call you.' It generated a big buzz with the local musicians at the time, but then nothing happened for six months. About the point where I'd forgotten about it, he called me for the audition.

"Frank gave me a list of difficult songs from several different records, and his instructions were, 'Figure out how to play and sing this the best you can, however you can.' The music was pretty complicated for a guy who was just playing in a bar band. I had never played in odd time signatures, and I didn't read music, whereas the rest of the Frank's band did. And I was so poor at the time that I didn't even buy the records. I borrowed them from my friends, because I didn't know if it was going to work out anyway.

"The audition was pretty brutal, and I didn't do very well. It was like the chaos of a movie set with people moving pianos around and so on. And there's little me standing in the middle of a room with a Pignose amplifier and a Stratocaster trying to sing and play lots of Frank Zappa songs. I was so nervous. I remember doing 'Andy,' and 'Wind Up Working in a Gas Station.' I thought I did poorly, and I had nowhere to go. I had just flown in, and was driven to his house, so I sat there all day watching everyone else. I watched some really tough auditions, especially for keyboard players and percussionists. I didn't see any other guitar players, but I was later told that he auditioned 50 guitar players.

"At the end of the day, when it all calmed down and people were finally leaving, I finally got my time to speak to Frank again. I said simply this: 'Frank, I don't think I did so well. I imagined this would have happened differently. I thought you and I would sit somewhere quiet, and I would play and sing the songs for you. And he said, 'OK, then let's do that.'

"We went upstairs to his living room, and we sat on his purple couch. I placed my Pignose amplifier face down on the couch so I could get a little bit of sustain, and I auditioned all over again. At the end of it, he reached out his hand and said, 'You got the job.' We shook hands, and that was an absolute turning point in my life."

Adrian Belew, "Anecdote #555, Part Two," Elephant Blog, May 17, 2007

The Audition For A Hand Shake.

my first phone conversation with frank went something like this:

frank: "do you read music?"

adrian: "no, I don't, but I can learn from records pretty well."

frank: "alright, here's a list of 12 songs. try to figure out how to sing

and play as much of them as you can. I'll see you here next week".I borrowed the records I needed to learn from

(I couldn't afford to buy them) and went into high gear.

every day for the next week I was consumed from morning till night

with learning frank zappa music.

man, it was hard.

the day came to fly to his house. it was the first time in my life I had been past the Missisippi. one of frank's crew members met me at the airport in a white cargo van. it was hot in california. the windows were down. he was shouting questions as he drove like a madman up the canyon's winding hills. I was deposited at frank's house. me, my strat, and my little pignose amp.

there was the beginnings of a studio in frank's basement. he sat behind a console chain smoking. I stood in the middle of the room with my little amp and sang into a microphone.

frank would say, "okay, try wind up workin' in a gas station". I would play and sing for a minute or two, he would stop me. "that's enough".

"now try andy".

I would play and sing for a bit and he would stop me.

and that's how it went.

the problem was the commotion. there were roadies rolling equipment around the room and people busy doing things to prepare for rehearsals. it seemed like there was an army in that small basement.

I knew I hadn't done well. I had nowhere to go until my flight back home so I stayed around all day watching other torturous auditions. I watched tommy mars' piano audition. it was frightening. but tommy was fabulous. I was told later frank had auditioned 50 guitar players!

as the day was ending and things quieted down I had a moment to say something to frank. I told him I knew I hadn't done well but it was not what I'd expected. I thought it would be the two of us somewhere quiet. he said, "well fine. let's go upstairs".

we sat on the purple couch in his living room.

I put my pignose amp face down on a pillow so it wouldn't be too loud.

and frank gave me a second audition.

at the end of it he reached over and shook my hand.

he told me I had the job for one year

and went on to explain his pay arrangements

(i.e. so much for rehearsal, so much for shows, etc.)with that hand shake my life was changed forever.

Adrian Belew, Halloween 77 (2017), liner notes

the first flight of my life was to Hollywood to audition for the position. roadie Tex Abel picked me at the airport and frantically whisked me through the LA traffic to Trapeze School, also known as Frank's basement. I felt so out of place in midst of the chaotic activity it took two scary auditions, but eventually Frank shook my hand and congratulated me.

Peter Wolf

Peter Wolf interviewed by Michael Davis, Keyboard Magazine, June 1980

How did you come to join Frank's band?

The reason that I stayed in the South was that I ran out of money; I wanted to come to L.A. right away. The Weather Report guys are old friends of mine and I know George Duke and [bassist] Alphonso Johnson, so I figured that when I came out here I could get in touch with them and they could turn me on to some gigs or something, which was totally wrong because nobody has time to do that here, but I had to figure that out for myself. So I came to town and I just got lucky. The singer that was in the band with Carl Ratzer, Lalomie Washburn, was doing an album and she said, "Why don't you do this thing with me?" So I did the album. She was renting from [Andre] Lewis, an old friend of hers who also knew Zappa. She must have played him some tapes and he must have liked them. So one day I was trying out synthesizers at the Guitar Center in Hollywood when [Andre] walks in the door and says, "You must be Peter Wolf" And I said, "Yeah." I gave [him] my phone number, and the next day at nine in the morning I got a call from Frank. "This is Frank Zappa; I'm looking for a keyboard player. Do you want to audition?" So I said, "Yeah, sure." And I came down, I auditioned, and I was in the band.

What does an audition with Frank consist of?

He first played me some tapes from the Zappa in New York album and checked out my reactions, I guess. Then he whipped some music in front of me to sight-read and I stumbled through it. First of all, I am not an excellent sight-reader, and then of course Frank's stuff is unbelievable to sight-read. That's part of his trip, I guess; he gets pleasure to a certain extent to give a player something he can't pull off. You have to practice that stuff, you can't just do it. Then he said, "Play me something." I took a piano solo. Patrick O'Hearn was there and he whipped out his acoustic bass and we started playing, just acoustic piano and acoustic bass. Finally, Frank said, "Well, what do you think, Pat, you want to play with this guy?" And Pat said, "Yeah." So Frank turned around and said, "You're hired." That was it.

Peter Wolf interviewed by Robert L. Doeschuk, Keyboardist, April 1994

I was in Los Angeles literally just two weeks when Frank Zappa called me. I did a job with Lalomie Washburn, a singer who was renting a room from Andre Lewis, the keyboard player who replaced George Duke in Frank's band. She played Andre some of the tapes, and he went to Frank's house to tell him about me. At that point, Frank was looking for a new keyboard player; he had auditioned, like, 60 of them. So he called me: "Hi, this is Frank Zappa. I'm looking for a keyboard player. Do you want to audition?" I said, "Sure!"

I went over to his place and went through the whole madness of reading "The Black Page." It was so hard! I can read anything that a studio gig in L.A. would ask me to read, but Frank Zappa material was beyond belief: seventeen tuplets followed by sixteenth-notes, and that's followed by quarter-note triplets. Nobody in the world can sight-read that correctly. So I would trip over these incredible rhythms, and he would go, "No, that's wrong. Try it again."

After a while, Patrick O'Hearn came in; he had already been in the band for a year. Frank said, "Patrick, why don't you play with this guy?" Patrick had his acoustic bass, so I played piano. We had a great time, because we were both jazz players. We were flying! Then Frank said, "You like to play with this guy?" Patrick said, "Yeah!" And that was that.

Mr. Bonzai, "Getting The Call, Giving It All," Keyboard, November 2007

I saved some money and came to California in 1976. I arrived here and met a lady by the name of Lalomie Washburn, who I met through a guitarist I had played with in Vienna. He'd come to America a year or two prior and was always telling Lalomie about me. So when I came to L.A., I called her and she said, "Why don't you come down to the studio? We're rehearsing for my new record on Casablanca."

I wound up recording the album with her, playing on it and working as musical director and arranger. Lalomie's roommate was Andre Lewis, a keyboardist and friend of Zappa. One day, I went to Guitar Center to try some synthesizers, and this tall man came over to me and said, "You must be Peter Wolf." I nodded, and he asked for my phone number.

Apparently, Frank had asked Andre if he knew any new keyboardists. Andre said he had heard "an Austrian kid who sounded pretty good." He gave Frank my number and the next morning—at 7 o'clock!—I get this call, "Hi, this is Frank Zappa. I'm looking for a keyboard player. Want to audition?" I said, "When?" And he said, "Now."

I drove up to his home and spent the entire day. He had a Bösendorfer Imperial grand, which the family still has, and he put all this heavy music in front of me. I stumbled through this hard, hard, stuff. I thought I would never get the gig. Then Patrick O'Hearn walked in, with outrageous long hair. I didn't know who it was at the time, but Patrick was the bassist for Joe Pass for years. We started playing and had a really great time. Frank asks Patrick, "Do you want to play with this guy?" "Yeah," says Patrick. Frank turned to me: "Okay, you're hired." That was it.

Ed Mann

Ed Mann, interviewed by Rick Mattingly, Modern Drummer, August 1982

RM: How did you get the gig with Zappa?

EM: John Bergamo had done a lot of orchestral work with Frank. About the time I graduated from Cal. Arts, John called Frank just to see what he was doing, and Frank was about to do the overdubs on "The Black Page." He gave John the music for that, John gave me a copy, and we both learned it. Before John went down to record it, he told Frank that I also knew the piece, so we both went down and recorded it. There are two versions: one is full band with mallets, the other version uses alternative sound sources—brake drums, pipes, the kind of thing Repercussion was involved in. We still had the Repercussion Unit at that time. So anyway, John and I did the overdubs on "The Black Page," and I met Frank then.

A few months later, Ruth [Underwood] told me that Frank was forming a new band and was looking for another keyboard player. I had known Tommy Mars since 71. We used to have bands together on the East Coast. He had just come out to California and was looking for a gig. So I called Frank up to get Tommy an audition. Frank remembered me and asked me if I would like to audition too, because he was also looking for a percussionist. That was June of 77.

RM: Did you have a formal audition?

EM: To a degree, but Frank already had a decent idea of what I could do since I had done some recording with him. It wasn't a "cattle call," which was fortunate. A lot of times, you'll see players come through those things, and when you have fifteen players waiting to audition, it's just "Next . . . next . . . next . . ." Depending on your ability to handle a situation like that, you may give a good impression of yourself or not, regardless of what your abilities are. So a lot of it is based on Frank's intuitive feeling at the time.

I think that had a lot to do with it when he asked me to join the band. When I went to the audition, it was about one o'clock in the morning. I had called him up about midnight, and he said, "Well, if you think you'd like the job, why don't you come up right now?" And I said, "Well, maybe tomorrow or something?" "No, no, if you want to do it, come up right now." So I went up and he had this really dimly lit room in his basement. He put all of the charts in front of me. It was an audition of sorts—he wanted to see how I could handle some of the music and how my basic sight reading was. I struggled through it, but I didn't feel I did a particularly good job. I suppose Frank just got the feeling I could handle it.

It took a lot of work that summer. We were rehearsing about six to eight hours a day, five days a week, and I would spend the rest of my time at home practicing it. I was just trying to get a basic feel for it. There are certain rhythmic patterns that Frank writes. You see them in different pieces and in different places, but it's all sort of coming from the same idea. It's not a formula; it's just a stylistic thing. Certain things occur here and there and you can relate them to other pieces. So I used all of my extra time to get a handle on how Frank wrote, his phrasing, and how he wanted things to sound stylistically.

Ed Mann, interviewed by Andrew Greenaway, The Idiot Bastard, March 14, 2004

[...] Ruth [Underwood] did call me one night late to ask if I knew any great keyboard players—Frank was looking for someone interesting and unable to find anyone. Tommy (Mars) had just moved out to California and so I said that I absolutely knew the guy for the gig—Ruth said call Frank RIGHT NOW (it was midnight)—so I did—and 3 hours later I was in the band. The next day when I called Ruth to tell her—she said, "I knew that would happen," in kind of a dismayed way . . . but she was a supporter, and was gracious. She also did quit the band several years earlier and if she had not, the gig still would have been hers.

[...] When Ruth called me at midnight, and then I called FZ at midnight, FZ seemed only mildly interested in the keyboard player info. But he said, "I remember you—why don't you come over here right now." So I did—it was about 1.30 a.m. when I got there. Patrick O'Hearn and Adrian were there too. Frank's basement: red velvet walls, muted yellow lights; dark. A big marimba with music stand sitting in the centre of this poorly lit room. First Frank put up the chart to 'Montana' and asked me to sight read it—which I did, but not really that well. Good enough to show that I knew how to figure stuff out I guess. There was some other bits and pieces—stuff that wound up in 'Wild Love'—and then Frank put on his guitar and said "OK—I will play a lick, and then you play it back to me on the marimba." That went pretty well. The whole time I was thinking "this is just entertainment for Frank," because when we had been in the studio recording 'The Black Page' several months earlier, he said out of the blue that he no longer would be taking any percussion on the road. Anyway, then Frank asked me to improvise—play a little solo, etc. I did that for a few minutes and then Frank says, "Great—you want to be in the band?" I just thought "WHAT?!?"—but I stammered, "Uh—yeah!" FZ extends The Handshake and then outlines the responsibilities, the pay, the schedule, and the expectation that I would have to buy all my own gear—he was otherwise purchasing gear for the keyboard players and guitarists—but that he did have some stuff I could use . . . then he pulled a 6-pack of Budweiser out of the fridge and we sat around for a half hour. Then he told me to arrive at 9 p.m. the next night for further planning, etc. I got home at 4 a.m. thinking, "Wow—what a day."

[...] Later on during the summer of 1977, I felt like I just was not getting some critical detail about how to play Franks' music on the marimba—Frank wrote stuff that required your hands move in directions that was opposite of the normal way that the arms will allow. So I called on Ruth and went over to her house so I could watch her play some of the passages. She played a little bit of 'Inca Roads', a bit from 'The Black Page', and a lot of Bach. That was very kind of Ruth to accommodate me—and I know that she was doing it for Frank as much as for me—and it did help. I adore Ruth—you gotta love Ruth!

Ed Mann, "Hired By Frank Zappa—Chapter 2: The First Week," Gonzo Today, August 17, 2021

Oh! . . . right . . . my new friend Ruth Underwood (Frank's virtuosic, legendary and only band percussionist to date) called me at 12:30 AM (!) declaring an emergency situation which Frank was in, concerning his failed attempt to locate an extraordinary genius keyboardist, yet even though I had a good suggestion, Ruth refused to take the telephone number I offered, insisting that Frank himself instructed her to instruct me (whom he didn't remember) to call Frank himself to give him the telephone number of The Guy (Tommy Mariano) personally.

So I called Frank himself, who answered immediately yet said he didn't remember me from The Black Page recording sessions, but then suddenly he did remember me, all the while expressing no interest in the keyboard player idea I was supposedly calling him about. Instead, Frank invited me up to his house to "mess around with some music" which we did for 10-15 minutes followed by a few questions, and then . . . he proceeded to offer me a job in his Band! Which made no sense, as he had made it clear during the recording sessions that he'd never use percussion in his band again, and last night was no real audition. And, I had accepted the offer. I began to realize what I'd impulsively committed myself to just hours before.

Why would Frank do that? No audition, and he knows I'm not up to Ruth's ability to play his music in strict, written form on a marimba.

Tommy Mars

Tommy Mars, interviewed by Axel Wünsch & Aad Hoogesteger, T'Mershi Duween, July-September 1991

I moved to Santa Barbara to pursue a solo career. I worked there for about four, five months. Then I got a call from Ed who I hadn't seen in a long time. He was living in Southern California and said that Frank Zappa was auditioning for a new band and would I be interested in taking the job. The only Zappa song I knew was 'King Kong' because me and Ed used to play it in World Consort. I said 'Wow yeah, I'm going for it', so I went down to LA. And I probably did for me the worst possible audition. Frank had a toothache and it was solo. I went to his house and everything was going terribly. He would play certain measures for me and then play it and then do another section; and doing strange rhythmic things that I hadn't done since college. But I was kind of making it. I just felt I was on a sinking ship but just holding on to everything.

He finally said after about half an hour 'Can you sing at all?' And I said 'Well, I probably know about a thousand songs Frank, but I'm so fucked up now with this audition.' He said 'Yeah me too.' I said 'Would you mind if I just improvise? I mean I can't remember a whole song all the way through; could I just sing and improvise?' He looked up at the sky like that and said 'That's the first good thing you've done today. Let's go for it'. And from then on, we were together. He just loved it; he even brought his wife down. And I'll never forget that moment. I remember there's a piece . . . I think it's 'Sinister Footwear' that I always used to sing. That part was wet; the ink was wet on that part. And that's what I was having an audition on. It was really interesting to see how his music evolved into different pieces. I'll never forget when he called Gail down and said 'Do that exactly again.' And I said 'All right; no problem.' I was feeling good.

[...]

Q: Did you create your sound, the brass sound, yourself?

T: Yes. Frank at first put me on retainer for a week. He said 'I want you to learn this music, that whole 'Sheik Yerbouti' shit.' Next time, I brought down my Electron synth. The guys from Emu were there at the time and he had two big Emu modules. And when he heard the Electron, he said 'I want that sound.' The Emu was very like my synth but on a larger scale. But I'll never forget it when Frank said 'Hardwire that thing just like his is, right now,' I felt like I was on the vanguard of the business. It was my distinctive sound. Now you hear it all over the place. I was the first person to use it, because there's no synth that made that sound before me. And it's a very warm sound.

Tommy Mars, interviewed by Robert L. Doeschuk, Keyboardist, April 1994

I had been earning a living in Santa Barbara as a choir master, organist, and solo jazz pianist when my friend Ed Mann, who was playing percussion with Frank, called and said that Frank Zappa was auditioning keyboard players. Aside from "King Kong" and "Peaches En Regalia" I didn't really know Frank's music. I just thought he was kind of a nutty guy. But he called me up, and I went down to his house.

Immediately, Frank puts me to the wall. He was still writing "Sinister Footwear," although it was called "Slowly" at the time. The ink was still wet on it. He said, "I want to hear how this sounds." I hadn't seen these kinds of rhythmic relationships since I was doing serious contemporary classical music in college. I read through it; it wasn't perfect, but at least I started and stopped at the right time, and that's reading to me. Then he played a couple of measures for me and said, "Okay, this is Section A. Here's Section B. Now play them A-B-B." Then he said, "Here's Section C. I want you to put A with C, then do two of B ..." I couldn't write any of this down, because he wanted to check my memory. It was baffling, with these strange guitar licks. I have perfect pitch, so that helped a bit, but I was like, "Holy shit! This guy is stretching me like freakin' gum!"

Then he said, "Hey, can you sing?" I said, "Look, man. I sing for my supper. I have to sing every night on these club gigs. I must know a thousand songs. But my head is so fucked up from this audition that I don't think I could remember the lyrics to one song all the way through. How about if I just improvise for you?" He gave me the strangest look, and he said, "Man, that's the first right thing you've done all day. Go for it, kid."

So I started wailing. For some reason, the last thing I did was that song from The Wizard of Oz, the one that goes, "Bzz bzz bzz, chirp chirp chirp, and a couple of la-de-dahs." I don't think I'd ever done that song before, but I played the most wild, insane version. And he totally broke up. He said, "Number one, just sit right where you are. Number two, I don't think you're ever going to play again in any more Holiday Inns. Number three, I'm gonna go up and get my wife; I've never heard anything like this before. Just hold tight." And he went upstairs.

While he was gone—I can't tell you how cosmic this was—I looked at some of the music he had in the room. And on the bottom of one sheet, it said, "Munchkin Music." I said, "Whoa! I think this is meant to be."

He came back with Gail and said, "I want you to do it again, exactly like you just did it." I said, "Look, man, that was an improv. But I can approximate it." I went for it, and Gail just fell in love with me. So Frank gave me 12 or 13 pieces and said, "I want you to learn this. I'm putting you on a temporary retainer." Back in Santa Barbara, as I went through this stuff, I was thinking, "My God, this is very Hindemithian," or, "These melodic ideas and rhythmic phrases are incredibly Stravinsky-like." It was barking at all the composers, yet it didn't sound like them. It was strictly Zappa's own hybrid. I noticed his passion for reiterated notes. To me, if you play one note, you've said it. But he always had to play the same note two or three times. That was a definite rhythmic characteristic.

A week later, I came back down from Santa Barbara; I had learned every piece that he gave me as a solo piano arrangement, even "The Black Page" and "Punky's Whips." He thought I would just learn the chords and some of the melodic licks, but I did everything as if I would do it solo. So he was utterly flabbergasted. The rest is history.

Tommy Mars, interviewed by Evil Prince, T'Mershi Duween, October 1997

Q: When did you meet Frank for the first time?

TM: I believe it was the first week in May 1977. I was playing solo in Santa Barbara at the Biltmore Hotel. I had a call from Ed Mann who I'd always been in touch with and who had moved to California a couple of years before I did. He told me Frank was auditioning keyboard players and he really sort of tooted my horn pretty well. Frank already had a keyboard player and he didn't really need another one, but Ed raved about me so much that Frank said 'I gotta hear this dude'. I thought Ed was putting me on when I got a phone call saying 'This is Frank' and I said 'Frank who?' I was getting tired playing solo piano in terms of the people who were in these hotels and piano bars. I couldn't put the right mask on any more. It was a situation where I would see perfect ladies and gentlemen come into the bar and after a few drinks, maybe an hour later, they would turn into animals. They weren't really listening to the music and they were really disrespectful even among themselves. I would start scat singing to just one of them, like (sings) 'You're just such a fucked-up dude. What the hell do you see in this asshole, dear?' And I would get fired! So when I got the call from Frank, it was like he was going to hire me to be me, finally. I was not really versed in his music at all. 'Peaches' and 'King Kong'; those were the only two Zappa songs I knew. But it was no big deal. He appreciated what I did.

Q: So how was the audition for Frank's band?

TM: Ooh, it was wild. The first thing I remember, walking into the pad, were all these airline bottles of Johnny Walker Red and you have to know that Frank didn't drink or do drugs. I'm saying 'Wow, he's a drinking dude' (Fialka laughs again) and he took a sip of this and I'm waiting for him to swallow it, but he just holds it and I think I've never seen anyone drink like that. Later on, I realise Frank would occasionally get a tooth-ache and he would just hold it on his gum. That was my first impression. I'm thinking 'Why doesn't he just buy a jug?'

Then we started the audition and it was really difficult. I think he made it extra-special difficult for me because he already had hired Peter Wolf the week before. The first part of it was riff recognition. He would play a part on a record for me and say 'That's A—you got that? Here's B. OK, play A twice then B once. OK here's C. Now play C then B twice, then C and A four times.' These were not like 'Mary Had a Little Lamb' licks. These were like 'Enter the Demon'. My heart starts pounding. I did halfway decent on it.

The next thing, if I remember correctly, was a very special part to me. The song that came to be 'Sinister Footwear' had the first twenty-two measures just written. I remember looking at that page and seeing three or four measures not done yet, and on top it was called 'Slowly'. I said 'Jeez, that looks like a very interesting piece'. He said 'Yeah, play it'. I said 'OK', but he didn't want it from the top, just from the part that goes (sings the bit that also appears on 'Wild Love'). That gave me such problems because I hadn't seen figures like that since I was in college. I could tell I was cracking a nut with him, he was getting pissed off. I was reading it, and that to me means feeling a harmonic rhythm. You continue, you keep going, you grab what you can, but I think he wanted to hear it perfectly. He wanted Mr. College Graduate to just like blow. I didn't drown at this point; I was treading water with a very little popsicle stick. I was really started to get frustrated. My self-esteem was waning at this point.

He asked me if I can sing and I said 'Yah'. He wanted me to sing him a song. I was so frustrated that I said 'Frank, I must know a thousand songs, but the way I'm feeling now, my head is so blown-out with this audition that I don't think I could remember one all the way through'. So I just created something on the spot and went for a stream of consciousness. He said 'That's the first good thing you've done all day long. Go for it.' I just took off. All the frustration I felt just blew. When I finished, I ended up with a bit of the 'Wizard of Oz' which just came in and I was playing it sort of McCoy meets Art Tatum. It was wild. I finished it and there was a space of time while he waited and I was wondering how he felt about it. He said, 'You know what? You're not going to have to play in any more Holiday Inns for a long time.' That was great!

He puts his arm round me and he said 'I never heard anything like that!' and he started spewing. He went off to get Gail and he wanted me to do it exactly again. I said 'Frank, that will never happen again the way it just happened.' So I had to approximate it; I could do that all day long. I love doing that shit. He said 'Good, you're going to get plenty of time to do it'. He brought Gail down and it was all sealed up and I was hired that day.

So scat singing in a way saved me. It put me over the edge. I think he was interested, but I don't know if I would have been hired. I knew that he knew that I could read music and that was important to him in that I knew different musical styles. I have literally have been through hundreds of auditions with Frank, to see other people, all instruments and I do have to say that mine was probably the most difficult I have ever seen.

[...]

Speaking of the technology, when I was hired by Frank, I didn't bring any gear down with me. It was just a preliminary audition. He had given me thirteen pieces to practice for a week. When I went down, the sound that the guys from the synthesizer company were constructing with Frank was the most simple, basic and disgusting pipe organ sound and that was the easiest sound you could make on a synth in those days. It was set up with two envelope generators for each oscillator. With my stuff, I had already figured out that with one of those envelope generators, I could make a pitch change that would approximate the inadequacy and inexactness of embouchure. With human expression, you don't have perfection. The imperfection makes it human and makes it real. Everything up to that point was aseptically clean and by this little pitch change, one oscillator would stay on the same note, the other would be slightly out. When I found this out having bought my synth, I thought it had a brassy quality to it. I was always chiselling away at it. So when I brought down this synth, he asked what sounds you could have. I said 'I don't have a lot of them' but I played him this one sound I had constructed and he was impressed that it sounded like a French horn. So he had the guys from EMU hardwire this sound to his synth. Frank was always in the vanguard.

[...]

I had quite a bit of freedom during the first tour. My solo was on 'Pound for a Brown' in seven, and that could be taken out quite a bit. When Frank gave me 'Little House' to solo on, I started out on unaccompanied piano with my tour space pedals (?) [Taurus bass]. Then Terry and I would do a duo thing for a little while, and then I set up a little vamp at the end of this that I could blow on. It was just like a dream come true. However, the difficult part of it was that the shows would sometimes get abbreviated. When we played the first American tour, it was the only time that I was in the band that we had a show that never changed. Ever.

Tommy Mars interviewed by Mick Eckers, Zappa's Gear, September 8, 2011

When I did my audition and Frank said "You brought some gear with you?" I brought my Rhodes, and I brought my Electrocomp, and my Taurus bass pedals, and he said "what's this?" and I undid it and I played something, and of course my signature sound was a French horn kind of brass sound that it did, it was my kind of signature, and his jaw dropped. I don't think he'd had ever heard a synth kind of do that kind of sound in that kind of expression that it was able to have.

And I said "this E-mu you that you have?", and he was just like so proud of his E-mu, this is so funny man!), and the only sound that he had on it, which is the easiest sound in the world to make, was a little pipe organ sound, an eight foot and a four foot, no envelope, no nothing, I said "you mean with all this that's all you got?" (laughs), and he says "Yeah?" and I said "Well I don't think you noticed that the Electrocomp is very similar, I could set this sound up exactly for you on the E-mu, and then you'd have five voices, you'd have complete polyphony". And in those days that was like, you know, going to the emerald city, like follow the yellow brick road!

Frank got so excited he says "OK, do that" and he tentatively hired me that day at his house, he said I want you to come back in a week, I'm going to give you this music and I just want you to play it for me and then pretty much, you'd be in the band. So when I came back the second week the cats from E-mu [Marco Alpert, Dave Rossum and Scott Wedge] were there, and I showed them what I had done and Frank says "hard wire it", so they did. So even if you messed with the knobs (except for the tuning, those knobs, they had to be free) but the rest of it, the envelopes, were pre-set; they were tied up in the back.

Axel Wünsch, Aad Hoogesteger, Harald Hering and Achim Mänz, "Urban Leader: Ed Mann and Tommy Mars interviewed in Wuppertal 10.3.91," T'Mershi Duween, #18-19, April-May 1991

One day Tommy went to his letterbox and found some junkmail. The mail was addressed to T Mariano, but on one letter from a company, there was a sticker with T Mar5. The sun was shining and he couldn't see it exactly. Instead of a 5, he saw an s, so instead of T Mar5, he saw T Mars and he decided to call himself T Mars ever since.

Bill Harrington

Bill Harrington, a.f.f-z

I was hired on the eve (as a last minute, after thought) for the '77 tour.

Bill Harrington, c. 2000

I was called unexpectedly, just before the fall '77 tour began. The previous Winter and Spring, I had been on tour with an English group called Gentle Giant. There, I had been responsible for the setup and maintanence of all keyboard instruments. Shortly before Frank's tour began, they decided they'd need another person to help with the enormous keyboard setup they'd accrued. So, without ever seeing a rehearsal, or meeting any of the band members, I signed on.

[...] I first met Frank in September of '77. I was hired at the last minute. I didn't get to see any of the rehearsals or meet any band members. I first saw him at the airport after our plane had landed. He walked up to me, introduced himself and welcomed me on board.

September 10, 1977—Aladdin Theatre, Las Vegas, NV

Phil Kaufman

Greg Russo, Cosmik Debris: The Collected History And Improvisations Of Frank Zappa (The Son Of Revised), 2003, p. 131

On September 11, 1977, the first night of a tour and Zappa's Las Vegas debut, road manager Ron Nehoda committed suicide in his Aladdin Hotel room through self-inflicted razor blade wounds. Nehoda spent about $10,000 on drugs and gambling at Aladdin's casino. Zappa's manager Bennett Glotzer called Phil Kaufman to take over as tour manager.

Dennis Mitchell, "Sonic Flashback: Frank Zappa at the Aladdin (October 7, 1981)," Las Vegas Weekly, November 26, 2014

[FZ's first appearance in Las Vegas], in the summer of 1977, was marred by the suicide of his road manager at the Aladdin Hotel after the band had left for their next gig.

September 18, 1977—Atlanta, GA

Tommy Mars, interviewed by Evil Prince, T'Mershi Duween, October 1997

When Peter had that solo on 'Wild Love', I can remember that I always wanted to have that burning Latin solo. Frank for some reason, didn't like us to burn sometimes.

There was one time that I wanted to solo so fucking bad on 'Wild Love' that during Peter's solo in Atlanta, I took my pants off and I was down to my bikini briefs and I went on front of stage and danced. And Frank was digging the fuck out of it. I was just weaving and bobbing to all the chicks that were up there. It was sort of like my solo, this was the best I could get. I don't know if Peter enjoyed it, but Frank said after the show 'I'm never going to ask you to do that, Tommy. But whenever you feel like it, PLEASE do it!' If you do one thing for Frank with the music, you are expected to do it that way every single time. That's a given in the equation. I thought I might have created a monster for myself during that show.

October 2, 1977—Quadrangle, Washington University, St. Louis, MO

Ike Willis

Bobby Owsinski, "Frank Zappa And The Black Page," The Big Picture, November 24, 2009

Frank was playing a gig at the Cobo Arena in Detroit when one of the janitors came into the green room with a guitar before the gig. "I just have to do this," the janitor said with an "Ah, Shucks" kind of attitude. Frank gave him the go sign and Mr. Janitor did a couple of songs. Frank thanked him and asked for his card. The band chuckled, thinking that would be the last time it would touch Franks's eyes, but six months later Mr. Janitor Ike Willis was on an airplane out to Los Angeles to sing on a record with the esteemed Mr. Zappa. And he sang on almost every record Frank made until the end.

Ike Willis, interviewed by Robert von Bernewitz, Robert, Musicguy247, April 10, 2015

When the beginning of my senior year rolled around, that's when I met Frank . . . October 2nd 1977. That was at the beginning of the Sheik Yerbouti tour. I was on the local crew, just to schlep equipment and help the guys set up the equipment. Frank and I just happened to meet. We made eye contact after I spent all day hanging out with his crew setting up the equipment. After the sound check, he called me over to his table in the hospitality room and just started talking to me. He did the usual 3rd degree . . . he asked me if I played instruments and what kind of stuff I was into. Then he dragged me back to his dressing room, when it was time for him to get ready for the show. He handed me his guitar . . . told me to play . . . told me to sing.

[...] He was basically asking me questions. What instrument I played and how have I been playing? . . . was I into any of his shit? I said "Well sure, I know some of your songs." He said "Well play me one." I played "Carolina Hardcore Ecstasy". I started singing it and he started singing along. Tommy Mars, Ed Mann, Patrick O'hearn, and Bozzio . . . Belew came in and he started singing along. It was like an old time hootenanny. Frank told me "Look, I have auditions every year for my band, after I get back from every tour. What I'd like to do is fly you out and have you audition for the band. I've been looking for a lead vocalist. I like the way you sing . . . I like the way you play."

October 22, 1977—Forum, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

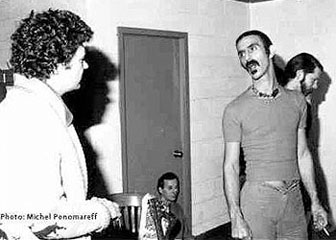

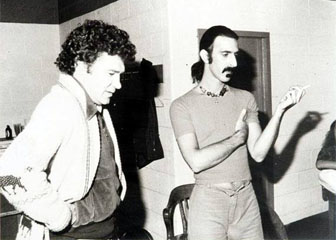

Photo: Michel Penomareff [Robert Charlebois, Adrian Belew, FZ, unknown]

Juan Rodriguez, The Gazette, October 24, 1977

The much-beloved Frank Zappa sits backstage at the Forum, waiting to return to the spotlight for his encore. One of his visitors was Quebecois singer Robert Charlebois for whom Zappa once did some unreleased production work.

[...] Back in the Forum dressing room, Quebecois superstar Robert Charlebois walks in, humbly bows and passes Zappa a note inscribed with a restaurant rendez-vous. "Thanks, Robert," says Zappa using the English pronunciation.

[...] They opened with the classic "Peaches in Regalia," a lovely composition from the late 1960s, before heading into the harder new material. A snappy rock number, "City of Time and Lights" ["City Of Tiny Lights"] competed with the heavy-rockers on their own turf. Another song chronicled the brags of Bobby Brown, a sleaze who sings in ecstacy, "Oh God, I am the American dream." "Coneheads" features some robotic dancing with the soundtrack making Star Wars seem like a tin box, and preceded a long instrumental saga, "Envelopes."

His protest against incompetence, "Flakes," pointed a scatological refrain directed at Warner Bros. executives. He saved two recent popular items for the encore, performed at near double-time: "Dinah-Mo Hum" the infamous 'sexist' tale, and "Camarillo Brillo," a laugh at some of the very fans who love Zappa so.

October 24, 1977—Philadelphia, PA

Charlie Walker, "Zappa And Company Delight Audience," Evening Journal, October 26, 1977

Frank Zappa and his massive travelling rock and roll show invaded the Spectrum in Philadelphia Monday night to unleash his latest assortment of well-orchestrated and yet still-insane musical creations.

Although too much of the evening was spent criticizing Warner Brothers Records, Zappa and his latest Mothers of Invention crew managed to project the perversion that has made him famous.

Zappa says in his press brochure that the musicians accompanying him are "THE BEST musical ensemble I have ever had the pleasure of unleashing on that jaded, disgusting world of POP MUSIC"—and he could very well be right. Even though Terry Bozzio tended to be a bit lengthy on a drum solo, the keyboard work of Peter Wolf and Tommy Mars, the string tandem of Adrian Delew on guitar and Patrick O'Hearn on bass, and the percussion work of Ed Mann represents a truly well-worked sound.

According to Zappa, this show has been in rehearsal for three months at a weekly cost of $13,200. The equipment weighs about 85,000 pounds, fill two 45-foot trucks, and takes five to six hours to set up and three hours to tear down.

Although Zappa based the show on many less than famous numbers, such as "Conehead," "Flakes," and "Envelopes," he dazzled the crowd with electronic wizardry and guitar genius. Frank Zappa really is an incredible guitarist, and the crowd roared its approval at the close of the performance in recognition of this.

Upon Zappa's re-entry to the stage for this encore, the crowd finally exploded after simmering all evening. They rushed into the aisles and filled the floor of what was an otherwise peaceful Spectrum. He appeased their desires with performance of the popular and requested "Dynamo Hum." Crouched at the edge of the stage, he crooned the perverse verse of desire. Then, jumping up and donning his orange sunglasses while picking up his guitar again, Frank and his gang blasted out "San Bernadino" for the finale.

November 19, 1977—Stanford, CA

Michael Snyder, "Rebel Without Applause," BAM, January 1978

So how come you're playing Palo Alto and passing on San Francisco?

Because of Bill Graham. He didn't want to pay the right amount of money. He has a monopoly on this town. I have nothing against him personally. I like Graham. He's quite a character, but business is business. When somebody doesn't want to pay me what it costs me to bring a show to town because he's got a monopoly on a certain area, I resent it and instruct my manager to deal with that person. To sit still on the road with 85,000 pounds of equipment and 20 or so people costs a fortune. Someone thinks this is a major metropolitan area that must be serviced. Big Deal.

Isn't that a prevalent attitude in other urban centers?

In a lot of locations, one guy will control all the dates in a town's largest public hall and wants to grab you by the weenie every time you go in there.