[Elmer] Valentine opened the Whisky à Go Go in January of 1964. Johnny Rivers, later famous for the song "Secret Agent Man," was the headliner. The club was an instant smash, a cultural trendsetter from the outset; we have Valentine to thank for introducing the terms "à go go," "go-go girl," and "go-go cage" into our vernacular, and, more significantly, for helping launch the careers of some of the best rock 'n' roll bands ever. "Once the Whisky started to happen, then Sunset Boulevard started to happen," says Lou Adler. "L.A. started to happen, as far as the music business—it blew up."

[...] "It was an amazing time," says Gail Zappa, who met her future husband, Frank, when she was 21 and working as Valentine's secretary. [...] Valentine was the scene's unlikely paterfamilias—an ex-cop and jazz aficionado from Chicago who was already past 40. "Back then, we really believed in 'Don't trust anyone over 30,' but Elmer was different," says Cher. "He was the one older person we trusted."

[...] In 1963 [Valentine] traveled to Europe with the intent of opening a club in one of the cities there and beginning a new life as an expatriate. But while he was in Paris, he happened to visit a discotheque that was called the Whisky à Go Go. "They had these kids, young people, dancing like you wouldn't believe," he says. "So I came back to Los Angeles, and I wanted to open a discotheque. I wanted that badly. 'Cause I saw what was happening—the frenzy and the people and the lines." Valentine had made $55,000 by selling his share in P.J.'s. He re-invested $20,000 of this money in the refurbishment of a failing club whose lease he'd taken over, a place at the corner of Sunset and Clark called the Party, in an old Bank of America building. The club's new name was nicked straight from Paris: the Whisky à Go Go.

[Lou] Adler advised Valentine to sign [Johnny] Rivers to a one-year contract as the Whisky's marquee act. Rivers agreed, the deal being that he'd play three sets a night, with a drummer and a bassist. Between sets, the audience would dance to records spun by a D.J.—but not just any D.J.: a girl D.J., suspended high above the audience in a glass-walled cage. This faintly ridiculous idea was Valentine's pragmatic response to the room's space limitations: the Whisky was not a big club, and the only way he could fit the D.J. booth was to mount it on a metal support beam that ran alongside the performing area. Making the most of the situation's public-relations potential, Valentine asked one of his early partners in the Whisky, a P.R. man named Shelly Davis, to run a public contest for the new girl-D.J. position.

But on the very night of the Whisky's opening, January 15, 1964, the contest winner called Valentine in tears, explaining that her disapproving mother wouldn't let her take the job. So Valentine pressed his reluctant cigarette girl, a young woman named Patty Brockhurst, into action. "She had on a slit skirt, and we put her up there," he says. "So she's up there playing the records. She's a young girl, so while she's playing 'em, all of a sudden she starts dancing to 'em! It was a dream. It worked." Thus, out of calamity and serendipity, was born the go-go girl. Valentine acted fast to formalize the position, installing two more cages and hiring two more girl dancers, one of whom, Joanie Labine, designed the official go-go-girl costume of fringed dress and white boots.

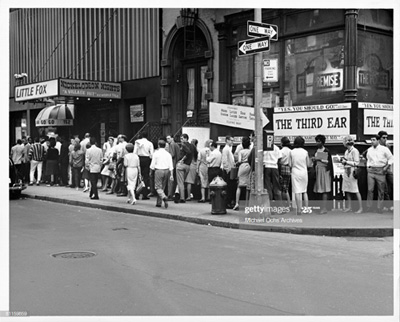

[...] The novelty of rock 'n' roll on the Strip, plus the added novelty of the girls, attracted national media attention and Hollywood stars.

[...] When the very first Byrds single, their famously jangly version of Bob Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man," went to No. 1 in May of 1965, it ratified the notion of the Strip as a progressive music scene, and the notion of folk-rock hippiedom as a way of life. "From '64 into '65, the focus shifted from Johnny Rivers east to Ciro's—on us," says Hillman.

[...] The Strip became a magnet for all sorts of budding hippies, runaway teens, and oddballs without portfolio [...]. With all things hippie and freaky taking hold on the Strip, Valentine, with the plugged-in [Lou] Adler serving as his informal musical adviser, began booking more outré acts after Rivers's residency ended—starting with the Young Rascals, followed by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, who even played luncheon dates (wearing derbies for some reason).

[...] Valentine turned a blind eye to the dealers selling acid in the parking lot behind the club, while the Whisky's new manager, an old Chicago acquaintance of Valentine's named Mario Maglieri, kindheartedly looked after the mongrel kids who now littered the club's doorstep, offering them friendly (if unheeded) anti-drug lectures and free bowls of soup. The Whisky reasserted its dominance. Not only did Valentine get prestigious U.K. acts like the Who, the Animals, the Kinks, and Them, he also instituted a policy of showcasing local bands in support slots and on the off nights when big-name acts weren't available. The roster of bands who played in the Whisky's "house band" slot—among them Love, Buffalo Springfield, and the Doors—is a testament to the wealth of great young talent milling around Los Angeles in the mid-1960s.

[...] The same [1966] summer of the Doors' residency, the police and the local merchants on Sunset Boulevard grew increasingly alarmed by the throngs of young folk on the Strip. The NO CRUISING ZONE policy took effect, and Sheriff Peter Pitchess's force bore down on the clubs, enforcing curfews and rounding up kids into paddy wagons. ("'Vagrancy'—that's what everybody got busted for," says Gail Zappa.) [...]

More consequentially, the Whisky's dance license was revoked by the city of Los Angeles. "Because they felt if the kids couldn't dance they wouldn't come in. It's like cutting my legs off," says Valentine. He successfully sued to get his license back, and counterpunched with a scheme of his own. As Gail Zappa tells it, "Elmer decided, 'O.K., I'm only gonna book black acts.' Which, by the way, were extremely popular. But overnight the Strip was black. The merchants really got nervous then. And Elmer thought it was a great joke."

[...] Even with the old in-crowd staying away, the Whisky lost little of its luster in the late 60s, remaining the premier venue for any band passing through Los Angeles—Valentine recalls with particular fondness Led Zeppelin's 1969 engagement, "five straight nights with Alice Cooper as the opening act." But as the decade turned and rock spread to ballrooms, arenas, and stadiums, the Whisky did begin to struggle. And when Valentine changed strategy in the early 70s, briefly turning the club into a legit theater and cabaret, the glorious heyday of L.A. pop was emphatically over.

[...] The place is still there and still turns a profit, and has enjoyed two significant renaissances as a scene nexus since its original run: first in the late 70s, when L.A. punk blossomed with such bands as X, the Germs, the Dils, the Weirdos, and Black Flag, and then in the 80s, when spandex metal took hold with Mötley Crüe and Guns N' Roses. Today, the Whisky is in the hands of Maglieri and his son Mikeal, to whom Valentine sold out just a year ago, as did Adler, who'd bought into the club in 1978. Valentine and Adler still own the Roxy, a larger club farther west on the Strip that they opened in 1973; and Valentine and Maglieri, despite a falling-out, are still partners (along with Adler) in the Rainbow Bar & Grill, the dark, beery-smelling rock 'n' roll pub up the block from the Roxy.